Perception isn’t always the same thing as reality, even when it comes to something as “objective” as your product’s value.

In fact, the perceived value of your product is fairly malleable. There are countless studies, as well as anecdotes, that support the notion that you can tweak small things to increase your product’s value perception.

Table of contents

- What is perceived value?

- Reality vs. perception

- The plasticity of perception (and price)

- The power of reframing

- Perceived value examples: why pricier wines (might) taste better

- Introduce an element of altruism

- Reduce perceived risk

- Improve different parts of the customer experience

- Product bundling: an curious example of perceived value

- Add a button that makes noise

- Conclusion

What is perceived value?

Perceived value is the evaluation that a customer makes of a certain product or service. This marketing concept depends on the customer’s opinion on how the product satisfies their needs, and as such, it may differ from the market price of that product.

A customer’s opinion of a product’s value to him or her. It may have little or nothing to do with the product’s market price, and depends on the product’s ability to satisfy his or her needs or requirements.

Perceived value also has some interesting interactions with perceived risks, price plasticity, long-term satisfaction, and loyalty, all of which we’ll explore here.

(By the way, much of this is inspired by Rory Sutherland’s Ted Talk. If you haven’t already, watch it.)

Reality vs. perception

According to Sutherland, one of the great mistakes of economics is that it fails to understand that “what something is, whether it’s retirement, unemployment, cost, is a function, not only of its amount, but also its meaning.”

The same product can mean different things to different people, and there’s no such thing as objective product value, at least when it comes to actually selling products. (There are objective costs associated with making the product, of course.)

Therefore, we have a huge opportunity to influence how people feel—how they perceive our product’s value—as well as the opportunity to optimize the customer experience to delight the customer and maximize revenue.

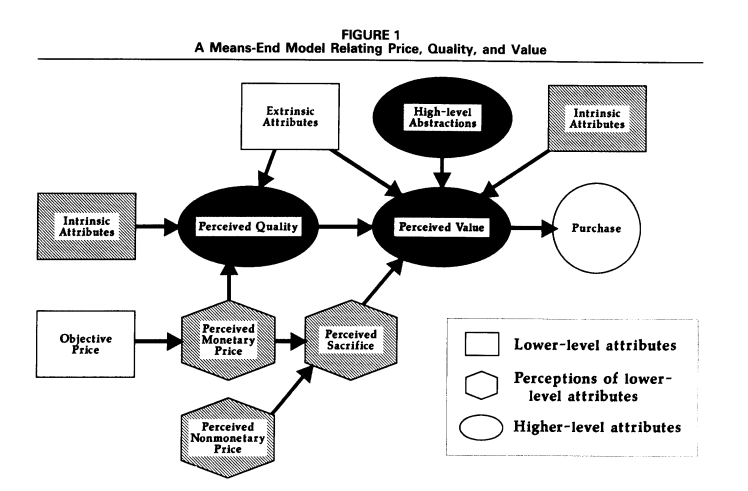

One common problem, though, at least in academic research, is the relatively ambiguous terms. What’s the difference between price, quality, and value?

Let’s say that perceived value is the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on what’s received and what’s given. This embodies more than just quality, which tends to be more product focused.

Perceived value, at least for the purposes of this article, includes concrete product attributes as well as other high-level abstractions like convenience, perceptions of security, service, and more.

The plasticity of perception (and price)

You can increase your product’s perceived value without actually increasing its objective value (i.e. the cost of making it). You just have to change people’s perceptions, and, as Rory Sutherland says, “our perception is leaky.”

There are many examples of this in the real world. To name a few:

- Research shows that branded painkillers are actually more effective at reducing pain. They’re the same “objective quality” pills, but we perceive one to be better, and so it is.

- People think washing their car makes it drive better.

- We irrationally value “free” things. Waiting in line for hours for a free doughnut ($3 value) doesn’t make any rational sense—but people do it.

- Too many choices can actually reduce sales.

Point is, there are many small tweaks and irrational things that can change our behavior. Not all of it is cost/benefit rational thinking. As Sutherland said in his Ted Talk:

We can’t tell the difference between the quality of the food and the environment in which we consume it.

All of you will have seen this phenomenon if you have your car washed or valeted. When you drive away, your car feels as if it drives better.

And the reason for this, unless my car valet mysteriously is changing the oil and performing work which I’m not paying him for and I’m unaware of, is because perception is, in any case, leaky.

And because value isn’t based solely on unit economics, you’ll want to experiment with value-based pricing. According to BusinessDictionary, perceived value pricing is:

The valuation of good or service according to how much consumers are willing to pay for it, rather than upon its production and delivery costs. Using a perceived value pricing technique might be somewhat arbitrary, but it can greatly assist in the effective marketing of a product since it sets product pricing in line with its perceived value by potential buyers.

Put simply, you’re pricing a product at what your customers will pay for it. It uses perceived value as a proxy for actual cost, which tends to be an efficient way to build a brand because of the elasticity. There are many ways to calculate optimal pricing, and, of course, A/B testing is one of them.

One of the most common (and effective) ways to increase perceived value is advertising. That’s largely the point of brand advertising. Similarly, public relations tries to attain some degree of control and influence over the public’s perception of a product or brand.

You can do it online, too. There are some pretty common and established ways of increasing your product’s perceived value (and in turn, increasing the amount you can charge for it).

The power of reframing

Sutherland gives an illuminating (and entertaining) example of reframing:

When you go to a drinks party and you stand up and you hold a glass of red wine and you talk endlessly to people, you don’t actually want to spend all the time talking. It’s really, really tiring.

Sometimes you just want to stand there silently, alone with your thoughts. Sometimes you just want to stand in the corner and stare out of the window.

Now the problem is, when you can’t smoke, if you stand and stare out of the window on your own, you’re an antisocial, friendless idiot. If you stand and stare out of the window on your own with a cigarette, you’re a fucking philosopher.

So the power of reframing things cannot be overstated. What we have is exactly the same thing, the same activity, but one of them makes you feel great and the other one, with just a small change of posture, makes you feel terrible.

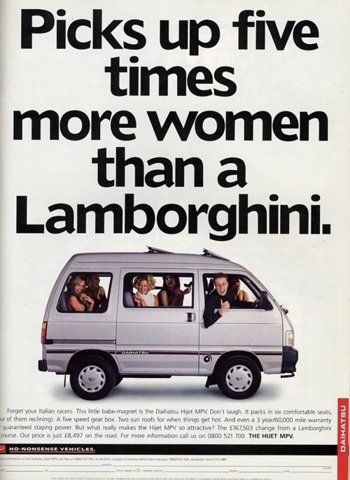

Indeed, reframing price is an excellent way to change the perceived value in a product. This has been done effectively in ads before, where the quality perception wasn’t necessarily changed, but reframing the cost attempted to decrease the perceived costs.

Here’s an example of cost reframing:

Two lattes a day seems doable (if you’ve got a caffeine habit like me). And a more humorous example:

Large amounts of money are especially conducive to reframing exercises. Copywriting is a great realm to try reframing things:

- Is it a “bargain,” or is it “cheap”?

- Is it “exclusive,” or is it “expensive”?

- Is it “comfortable,” or is it “tacky”?

You’ll have to bring out your inner spin doctor because there are endless ways to execute.

Perceived value examples: why pricier wines (might) taste better

People are largely irrational in their judgment of wine.

First, as studies have shown, even experts can’t tell apart cheap and expensive wines in blind taste studies. So there’s that.

Second, and more pertinent to our “increased value perception” question, is that the price actually affects the taste of the wine.

As Freakonomics put it, “When you take a sip of Cabernet, what are you tasting? The grape? The tannins? The oak barrel? Or the price? Believe it or not, the most dominant flavor may be the dollars.”

Researchers at Stanford GSB and the California Institute of Technology found that if a person is told they’re tasting two different wines—one costs $5 and the other $45 (but they’re actually the same wine)—the part of the brain that experiences pleasure will become more active when the drinker thinks they’re having the expensive wine.

In addition, they did a study where the participants said they could taste five different wines (when there were only three) and that the wines that were more expensive tasted better (even though they were the same wines).

While they didn’t test this on wine connoisseurs, the researchers expect they’d have similar findings. As they said, “We don’t know, but my speculation is that, yes, they will. I expect that the enophiles will show more of these effects, because they really care about it.”

Why people love exclusivity

Again with a wine study—this one had subjects read about a white wine that was described as either scarce or widely available. Subjects were also either informed or not informed of the wine cost. Then subjects evaluated the wine based on expensiveness, desirability, etc.

When the subjects weren’t told how much the wine cost, the researchers found that scarcity enhanced perceptions of expensiveness and desirability. Makes sense. Scarcity is one of the pillars of modern persuasion.

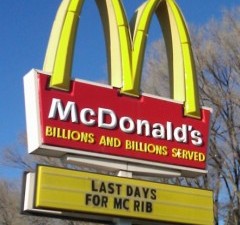

You can base scarcity on quantity or stock, but you can also have a time constraint. Otherwise, why would people like Shamrock Shakes or McRibs so much?

The strategy of scarcity works even better when coupled with premium pricing, say in the case of luxury goods, or wine (per our study above). As Seth Godin wrote, “social proof among the wealthy is based on beauty plus scarcity plus expense.”

And then there’s the simple case of people wanting something simply because they can’t have it.

This was most famously exemplified by Frederick the Great, when he rebranded potatoes as a royal vegetable. They made it exclusive to the royal family and hired guards to protect the potatoes.

Eventually, people started growing potatoes in secret, and they became higher value in people’s minds.

People want what they can’t have.

Introduce an element of altruism

Even though it’s more expensive than Trader Joe’s, I never feel bad about shopping at Whole Foods.

These guys wrote the book on Conscious Capitalism. John Mackey, the CEO, has said that “a certain amount of corporate philanthropy is simply good business.” It works well for them.

In a normal grocery store, there are so many decisions to make regarding quality and value, not to mention feeling good about the source of the food. Whole Foods makes it simple, and there’s value in that (reflected in the price, too).

Another company that does well with this model: Crate and Barrel. They spend some of their advertising budget on gift certificates for customers to finance projects on DonorsChoose.

The gift certificates, of course, have a big impact on the charities funded (347,000 students have benefited from 14,500 funded projects) and on consumers. But people who use gift certificates to fund projects were also found more likely to shop at Crate and Barrel for future purchases than a control that didn’t receive certificates (82% vs. 76%).

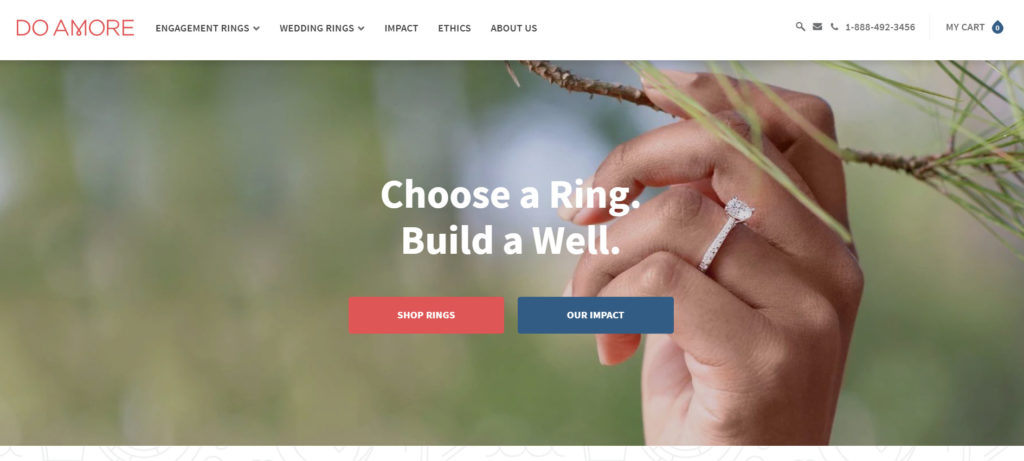

Altruism is the value proposition for some companies. Take Do Amore for example:

They give two people water for life when you buy an engagement ring, so you can feel even more awesome about an already special occasion.

Research largely supports that we appreciate products more with a hint of altruism. A survey found:

- 94% of consumers report that they would switch to a brand that supports a cause.

- 20% would buy a more expensive product if it supported a cause.

Corporate altruism creates a halo effect for the company, increasing the perceived value of its products.

Another study found that participants who were told of a winery’s socially responsible choice rated the wine as better-tasting than those that were not. While this effect was “was more pronounced for respondents reporting lower levels of wine expertise,” it can’t be understated.

The researchers also found similar results in hair-loss and teeth-whitening treatments. They wrote that the effect seems to be strongest “in cases where product quality is not readily observable, and/or consumers do not have clearly articulated preferences.”

Reduce perceived risk

The other side of the coin is the perceived sacrifices the customer has to make, including time, costs, risk, or security.

These embody a concept known as “perceived risk”, or a “consumer’s level of uncertainty regarding the outcome of a purchase decision, especially in the case of high-priced item, such as a car, or a complex item, like a computer.”

When there is high perceived risk, consumers try to reduce their fear by gathering more information and looking for social proof. Anything that quells their doubts reduces their perceived fear. And research suggests that when perceived fear is lower, perceived value is higher.

Bolster security and credibility

There are so many ways to increase credibility (or accidentally kill credibility). Just a few ideas to boost credibility:

- Money-back guarantees;

- Free-and-easy return policy;

- Trust/security symbols.

- Clear contact information.

Seriously, there are so many ways to bolster credibility and perceived security. Start with this credibility checklist.

Add proof

If you’ve got proof that people love your product, show it. This could be through customer testimonials, a famous spokesperson, or social media feedback. This could also be through product demos, case studies, explainer videos or whitepapers.

Show how your product works and that people love it. Our conference has some rave reviews, so we show them (in addition to last year’s video, etc.).

Improve different parts of the customer experience

Sure, you can reframe your price, make it higher, or make your product more exclusive. But you could also focus on providing delightful experiences surrounding your product.

Yes, you could look at this as improving user experience and usability in the traditional sense (and that’s a huge opportunity in optimization). But I’m speaking more broadly. What can you do to improve packaging, service, design, or convenience?

Here’s an example: When shopping for toys, people will choose the one with the larger packaging even if they’re the same value. Weird, right?

In addition, free shipping (or fast shipping) is highly effective at increasing conversions. (Though make no mistake—this is an operations decision that affects profit margins.)

Sutherland used the example of a restaurant to convey how other details can matter more than the product alone:

Try this quick thought experiment.

Imagine a restaurant that serves Michelin-starred food, but actually where the restaurant smells of sewage, and there’s human feces on the floor.

The best thing you can do there to create value is not actually to improve the food still further. It’s to get rid of the smell and clean up the floor. And it’s vital we understand this.

Product bundling: an curious example of perceived value

Product bundles are a “tried and true” marketing strategy. You’d think that bundling products would create the perception of a higher value—after all, you’re objectively increasing the value of your offer simply based on quantity. But it’s not always that simple.

Sure, bundling has a multitude of use cases. HBR gives the example of an expensive hotel room ($750). Even though consumers are forking out a lot of money for the room, they’d still be upset at paying for a $10 bottle of water. That is, unless you just made the room $760. It’s opaque and makes you more money while the consumer stays satisfied.

In that sense, bundling serves the seller. It’s simple (only one product to market), it’s opaque, and the basic users subsidize the long-tail features used by a smaller amount of advanced users. (Think Microsoft products.)

But there is one glaring exclusion: When you try to bundle an expensive product with an inexpensive one, it can actually lower the perceived value.

The same HBR article notes that people were willing to pay less for the bundle than for the more expensive product alone. They also found that people were more likely to purchase a $2,299 home gym when it was offered alone than when it was combined with a fitness DVD.

Most surprisingly, while people were willing to pay $225 on one piece of luggage and $54 for another when purchased separately, they’d pay only $165 for the items as a bundle ($60 less than the expensive one alone).

As HBR writes, “this suggests that the popular strategy of adding premiums to products can sometimes hurt, rather than increase, sales.”

Product bundling, then, is not a silver bullet. There are ways to do it right, though. Here’s Roger Dooley on how to do bundling correctly:

“If you are thinking about bundling multiple products, do it right:

- Avoid mixing a cheap item and an expensive item and simply promoting the package.

- If you are mixing products with different values, establish the value of the individual items first, particularly the most expensive one.

- Take a lesson from infomercial producers and emphasize the additive nature of bonus items.

- Focus on non-price attributes of the product (e.g., durability or comfort) – the researchers say this will reduce the devaluation effect from mixed-value items.”

Add a button that makes noise

Neuroscientists did a study and found out that you can increase perceived value without adding anything to the product—except a button that makes noise.

They had participants look at images of food, but before doing so, they asked each person to state how much they’d be willing to pay for general food items. Then, they were presented pictures of food, some with a button that, when pressed, made a related noise.

Afterward, participants were asked to chose between two food items that they had selected (prior to the study) of equal value. Oddly enough, they chose the item associated with the button and noise 60–65% of the time. When asked, most participants also said they’d pay more for the item, too.

Not sure if there’s an application here for SaaS or ecommerce (there are purported use cases for dietitians and those designing vending machines), but let me know if you test it.

Conclusion

So there it is—you can increase the perceived value of your product without increasing your own objective costs. This has the clear benefit of allowing you to make more money, but it’s not all self-serving; customers want to feel good about their purchases, too (and they tend to be more loyal when they perceive the value to be high).

Of course, these aren’t all the ways you could increase product value. That list would be never ending (or at least a book’s length). But the ideas listed above are commonly used and have some empirical support for their effectiveness.

Working on something related to this? Post a comment in the CXL community!

nice tips for us

Thanks so much for this article, and that fantastic TED talk. I hadn’t watched it before.

For another extremely valuable resource, please consider “The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing ” by Thomas T. Nagle and John Hogan. I’m not sure which edition is current. The book lives up to its title. You’ll be glad you read it.

Alex, excellent read. What do you think is the underlying principle behind the higher perceived value when presented with the noise? I can’t really explain this from a neurological point of view yet and I’d love to hear your opinion.