When it comes to subscription product pricing, you’re not just guessing, are you?

Years ago, an HBR study famously claimed that a 1% improvement in price would increase operating profit by 11%, making it the most effective thing you could tweak to increase business performance.

Pricing is important. It’s also one of the most difficult (and more technical) Ps of marketing. When you bring subscription pricing models into the mix, things get even more complex.

This post delivers clear, actionable strategies.

Table of contents

How do you determine value and price?

There’s no way around it. You have to talk to customers and do some research to get accurate pricing. Patrick Campbell, CEO of Price Intelligently, put it well in a GrowthHackers AMA:

You should not be afraid to talk to your customer about pricing. It’s not a secret you’re going to charge them at some point, and acting like it is a secret is doing you and the customer a disservice, because they need you to stay in business if they’re going to get long term value out of the business.

The other reason it’s so important is that the ONLY data source that’s going to tell you what your value is, is your customer. No one else, no formula, no workaround, is going to get you to this answer, so just go head first and ask them.

However, you can’t just ask your customer, “What would you like to pay for this?” (Well, you could, but the Pay What You Want strategy is a whole other article.) Instead, a variety of research techniques have been developed and used through the years. Here are four popular ones:

- Gabor-Granger technique;

- Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter;

- Brand Price Trade-off;

- Conjoint Analysis and Discrete Choice Analysis.

Note: if you’re a startup, these techniques might be overkill. Ryan Farley from LawnStarter mentioned that getting on the phone with customers and gauging reactions to prices worked well in the beginning:

I’ve found it best to do pricing experiments over the phone—the qualitative feedback you get can be just as valuable (if not more) than an A/B test.

Trying to sell someone on a premium package at a higher rate, then hearing “that sounds pretty reasonable” or “you’re out of your mind for trying to charge that much” is super valuable, especially when combined with all the other qualifying questions you ask.Sure, these phone sells cost time and money. But it’s an example of doing things that don’t scale to figure out what does.

That said, if you’re in an established market, these four techniques are popular and effective:

1. Gabor-Granger Technique

The Gabor-Granger Technique is a simple technique based on asking people the likelihood of their purchasing a product at different prices.

To simplify it, the technique involves asking a series of questions like, “Would you buy [product] at [price]?” The price then goes up or down depending on the response to the first question. The series continues 2–3 more times, until the consumer won’t go higher or lower.

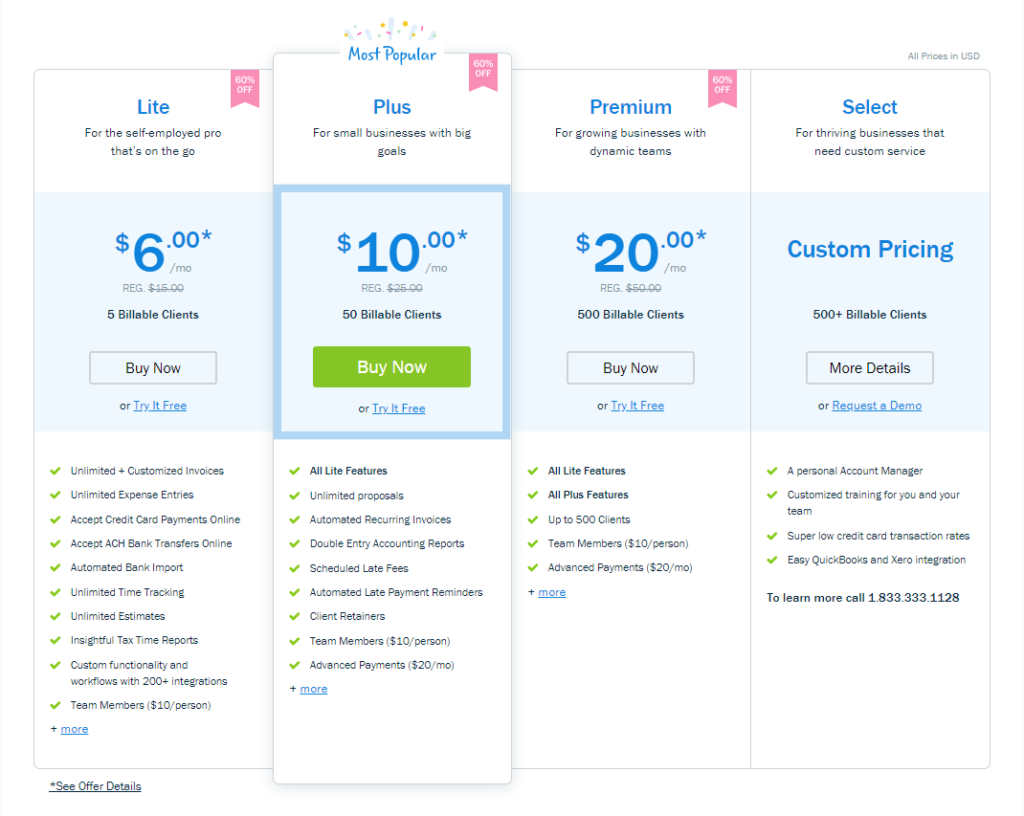

Here’s a sample chart based on Gabor-Granger data:

You can clearly visualize the percentage of people who would buy at a given price (in the chart above, just 3% of people would buy at $41), and you can determine which price would maximize revenue.

Use this technique to figure out the maximum price people would pay and to see the optimal price based on the number of people willing to purchase, as well as the maximum revenue.

2. Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter

In the van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter, respondents are asked four questions:

- At what price would you consider the product/service to be priced so low that you feel that the quality can’t be very good?

- At what price would you consider this product/service to be a bargain—a great buy for the money?

- At what price would you say this product/service is starting to get expensive—it’s not out of the question, but you’d have to give some thought to buying it?

- At what price would you consider the product/service to be so expensive that you would not consider buying it?

In this way, it’s more indirect and can determine price elasticity as well as an accurate range of effective pricing for a product.

According to GreenBook, this strategy is often used during new product development, and can help determine which pricing strategy is best:

Whether a client is contemplating an aggressive entry price strategy or a premium skimming approach to price, the van Westendorp PSA can help determine which strategy is best. Established brands will use the PSA model to guide pricing for re-positioning or other pricing decisions, often as input to a test market.

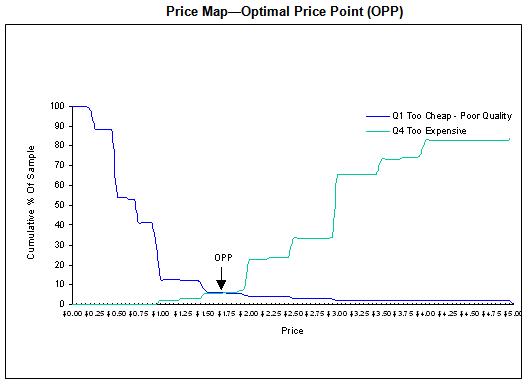

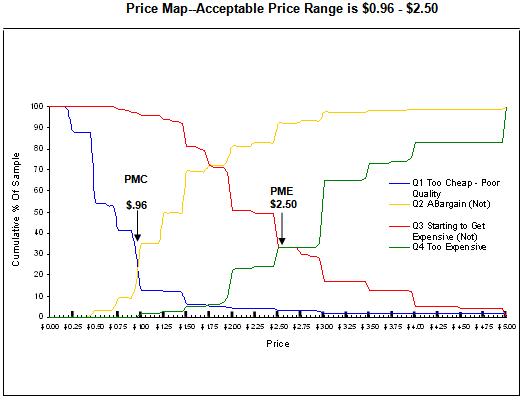

Here, the data shows an optimal pricing point:

And it can also show a pricing range:

This technique is perfect for subscription products with multiple tiers.

3. Brand Price Trade-off

Brand Price Trade-off (BTPO) is a statistical technique to measure your relative “brand value” or “brand equity.” Basically, it does this by modeling the relationships between your brand and the price it commands relative to other brands and the prices they command.

More than other techniques here, it answers how much your market is willing to pay for your brand in relation to similar products from other competitors—which makes this a competition-based pricing technique.

According to B2B International, “It is suited to categories where products and services are relatively similar to each other, and where brand is a strong determining factor behind decision-making.”

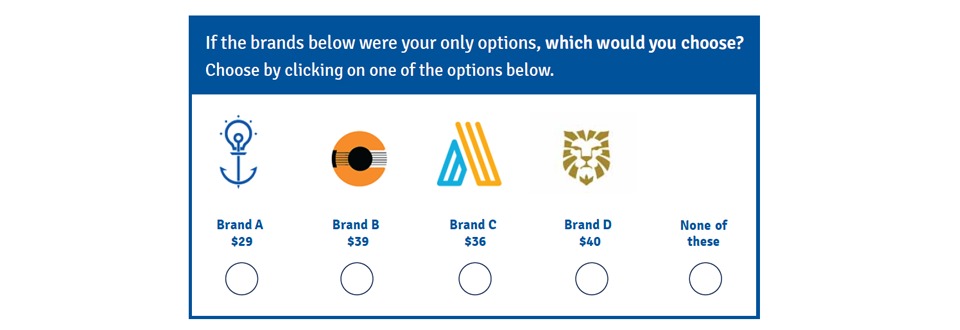

Here’s an example of a BPTO exercise:

To reiterate, use this is product categories with little differentiation and where brands make a huge impact on pricing.

4. Conjoint Analysis and Discrete Choice Analysis

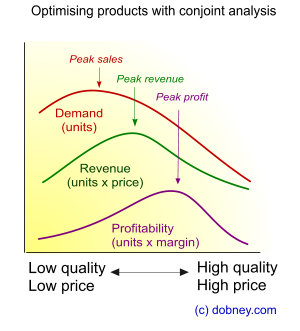

Conjoint analysis is a statistical technique used in market research to determine how people value different attributes (e.g., feature, function, benefits) that make up an individual product or service.

Discrete Choice analysis is similar. The difference is that in conjoint analysis, respondents evaluate the product configurations independently of each other, whereas with discrete choice analysis, they consider the options simultaneously.

The purpose of both is to “yield a measure of the relative importance of each attribute, and a measure of the strength of influence of each level of each attribute.”

This is how GreenBook explains it:

Perhaps the most commonly-performed simulation today is to calculate an attractiveness rating for each of all possible product configurations, and then sort the configurations by their attractiveness ratings. This allows us to identify the most preferred configuration (of all possible). In addition, if price is one of the attributes, and cost information is available, the most profitable combination of features can be identified.

These techniques have wider applications than just pricing but can nonetheless determine the values of certain product attributes and inform pricing.

Subscription pricing plan tiers

Nathan Barry described a huge mistake he almost made—having “only one price for your product.”

As he explained, you should price based on value, but the value derived by two sets of customers can be totally different. On that same note, he relates the study by about beer prices with different tiers.

In the study, researchers first offered participants two beers: premium beer for $2.50 and a bargain beer for $1.80. Roughly 80% chose the more expensive beer.

Next, a third beer was introduced—a super-bargain beer for $1.60. Now, 80% bought the $1.80 beer and the rest the $2.50 beer. Nobody bought the cheapest option.

In that case, the seller actually lost revenue through bracketing because they bracketed down the price.

However, the third time, they removed the $1.60 beer and replaced it with a super premium $3.40 beer. Most people chose the $2.50 beer, a small number the $1.80 beer, and around 10% opted for the most expensive $3.40 beer.

Some people will always buy the most expensive option, no matter the price.

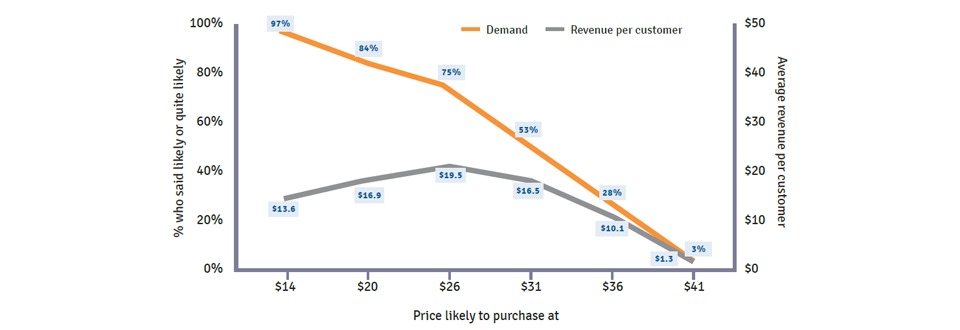

How many pricing tiers should you offer

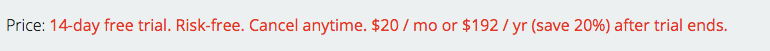

But is three pricing tiers the ideal offering? It would seem that way looking at most SaaS pricing pages. However, the number of tiers you offer actually depends on a few factors.

This depends on the number of customer personas/customer variations you’re targeting. Each persona should align to a respective tier, because then you ultimately have funnel-product-pricing alignment and your little SaaS machine should purr like a kitten.

There isn’t a magic number, but in this ebook we walk through what we see on average in the market – typically you’re looking at 3-5, but we’ve seen people with 1, 2, or 6+ plans be super successful, too.

Once you’ve aligned your customer personas to different tiers, you can use one of the pricing research strategies listed above and optimize from there.

Which order is best?

Should you list your pricing from low to high or high to low? There are examples of successful companies that do each, of course.

So which works better? It turns out that, generally, high-to-low works better.

According to Lincoln Murphy, “all things being equal (and equally good), the left to right, high to low approach seems to provide a statistically significant lift every time.”

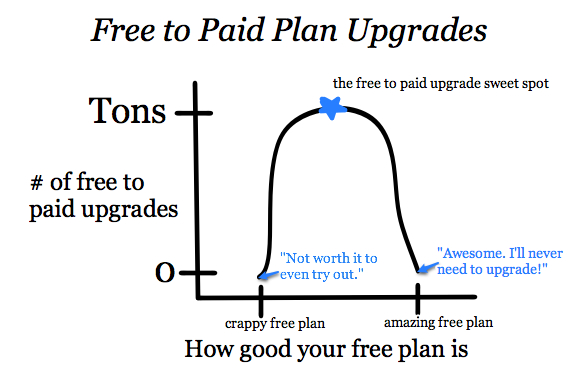

A quick note on freemium

Freemium isn’t really a revenue strategy but rather a customer acquisition strategy.

As Campbell put in, “You need to think of a freemium tier as a really expensive e-book. I know that’s a trite comparison, but when you think about it as lead-gen, then you’re starting to think about it correctly.”

In many cases, freemium pricing has been shown to kill growth, especially early on in your company’s history (not always of course). However, don’t be afraid to offer a short free trial.

Changing your subscription pricing

Once you set your prices, that’s it. They’re set in stone until your seed funding runs out and your company collapses. (Kidding, of course.)

In fact, Campbell recommends that you re-evaluate your pricing’s performance every three months, even if you’re a huge company. As far as changing pricing goes, he says you should make changes about every 6–9 months, more if you’re a smaller, nimbler company.

As for how to change prices, it’s a similar qualitative/quantitative research process that we outlined above for establishing prices. Here’s how Campbell explains it:

I’d then collect this type of data from current customers, prospects, and target customers who have never heard of you (we call them market panelists) to figure out what the value truly is in this feature or set of features.

You may find current customers are super biased because they love or loathe you so much that it taints the data pool. You may also find prospects don’t care, but ultimately this data allows you to then figure out if you should:

1. raise the price, because the feature(s) boost value so much,

2. simply include the feature as a retention mechanism (it’s ok for customers to be willing to pay more than prospects, because that means they’re loving the product, or

3. not build the feature out at all because it’s not going to provide proper value.

How much of a price hike is too much? While there is no magic number, Weber’s law suggests that customers get aggravated around a 10% increase. But you’re going to do the research anyway, of course.

Annual pricing plans

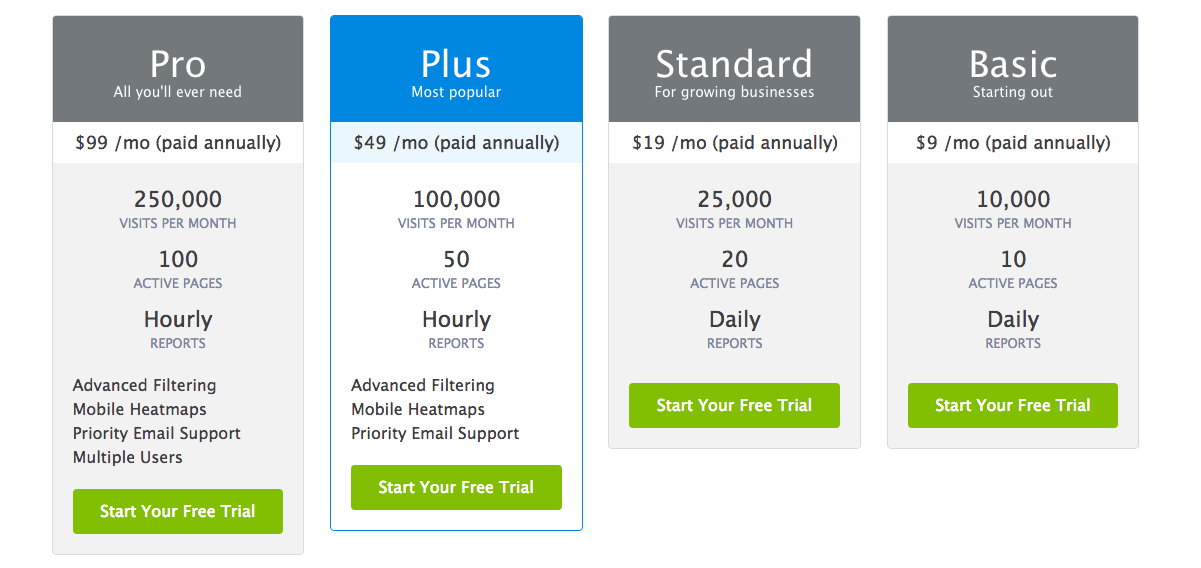

Every subscription product should offer an annual plan.

Why? Look up the Time Value of Money. If you’re too lazy, think about it logically from a cash flow perspective—more cash flow upfront allows you to invest in whichever ways you choose, while also not worrying about losing that customer for at least a year.

According to a Price Intelligently study, only about one in five SaaS companies offer monthly and annual plans. That’s too bad: “monthly payments may be the lifeblood of your business, but annual subscriptions secure you more business upfront, increase cash flow, and reduce churn.”

Andrew Tate expanded on this on ProfitWell’s blog:

But having that money up front means that you can make more investment in your business, growing your user base and boosting your revenue.

A lump sum payment into your bank account can be a lifesaver for a new SaaS business. It can help cover customer acquisition costs and allow you to invest in your company, paying for office space, key new hires, and great SaaS services yourself.

In turn, this increase in investment means that you can spend more on customer retention, more on customer acquisition, and more on great people and your product, which will itself boost your bottom line.

Annual plans often have better active usage and retention than monthly plans, too. The individual made a bigger investment in the product upfront, so they’re more invested in the overall product.

How to implement an annual pricing plan

Price Intelligently recommends discounting your annual subscriptions 15–20%, but it all depends on your audience’s price sensitivity. Use one of the pricing research strategies above to accomplish that.

Something like “1 month free” or “2 months free,” notes Campbell, works much, much better than saying “X percent off.”

One mistake to avoid is measuring your yearly members as MRR for the month they purchased. Instead, make sure you divide your yearly plan by 12 for your MRR.

Some companies even push it so far as to offer only annual plans (good for them, annoying for us):

Pricing tricks and tactics

To be clear, psychological pricing tricks should be secondary to your fundamental pricing strategy. Campbell calls it “the last 5%,” all of which you could still test for greater revenue:

You need to make sure your core pricing process is pointing to success or failure in your pricing strategy, because if you really should be priced at $100 and you’re priced at $20, it doesn’t matter if you put “$19” – you’re still going to lose in conversion and monetization…

…If the foundation of your strategy sucks, no amount of “end your prices in 9s” or “just add an annual plan” will solve your problems. Too many people rely on “best practices” that haven’t been rooted in anything, but a lot of people saying they work. You need to test and collect data. If you’re not doing this in pricing, you’re leaving an extraordinary amount of cash on the table.

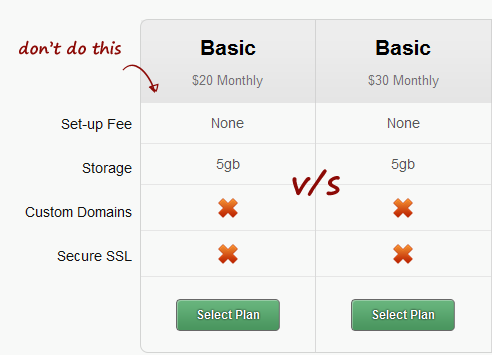

Still, here are a few popular and effective pricing plan tactics:

- Decoy pricing is now one of the most popular pricing studies. Dan Ariely showed that adding a “decoy” can prod people into making the choice that you really want them to make. So, if you add a slightly worse option that is similar to A (call it A-), then it’s easy to see that A is better than A-, hence many people choose that.

- What’s the best way to sell a $2,000 watch? Put it next to a $10,000 watch. Anchoring is a strong mechanism. (It’s the reason restaurants put a drastically pricier food or wine option on the menu.)

- Eliminating dollar signs (24 vs $24) has been shown to increase spending at restaurants. Does it work with SaaS? Not sure.

- In eight studies published from 1987 to 2004, charm prices ($49, $79, $1.49, etc.) were reported to boost sales by an average of 24% relative to nearby prices. End your prices in 9s.

- Some studies suggest that consumers perceive a sales price to be better valued when it’s written in a smaller font. Physical magnitude correlates to numerical magnitude in our minds. Try using smaller font sizes for discounts.

- Researchers found that more syllables make prices seem much higher (e.g. $1,499.00 sounds much higher than $1,499). Use fewer syllables.

If you want to go down the rabbit hole of psychological pricing strategies, there’s no shortage of good resources:

- Pricing Psychology: 10 Timeless Strategies to Increase Sales;

- Pricing Experiments You Might Not Know, But Can Learn From;

- 10 Examples of Great Pricing Strategies;

- Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely.

Well, can you A/B test pricing?

You can, but most people don’t recommend that you A/B test pricing. To set up a controlled experiment (in which you offer the same product for different prices to different people) opens you up to potential PR blowback.

Functionally, too, A/B testing isn’t always the best way to determine pricing. Campbell cautions that “A/B testing for optimizing your pricing structure and determining your true price point is a terrible idea; it’s a downright awful one.”

And, as Eric Yu from Price Intelligently put it:

A/B testing is never the best option for determining an optimal pricing strategy for your company. The practice works great for a lot of things, but its relative nature does more damage than good when coming to the most important aspect of your business. You’re much better off just speaking and sourcing information from your prospects, leads, and current customers.

A/B testing can cause some adverse anchoring effects. In addition, it’s iterative and contextual, not absolute. Even if B beat A, that doesn’t mean B is the optimal price point for your product.

However, there is one potentially effective way to A/B test subscription pricing. Split test two different prices (say $29 and $39 a month), but when the customer reaches the checkout page, charge the same price ($29) for both variations.

This way, you can test price elasticity without any PR blowback or adverse anchoring effects. (By giving them the lower price as the final price, they won’t be aggravated that you “tricked” them at the checkout.)

Conclusion

Pricing strategy is hard. It’s also of utmost importance, so putting effort into optimizing it is well worth it. A few quick tips:

- Don’t guess.

- You actually have to talk to customers to get good data. There are tried-and-true market research methods to determine accurate pricing.

- Offer multiple tiers for your different customer personas. Price them based on the research you’ve done within each persona.

- Don’t do long-term or drastic discounting. That anchoring thing works both ways.

- In most cases, don’t hide pricing or keep it secret.

- Evaluate pricing every three months. Think about changing it every 6–9.

Hi Alex,

Thanks for this detailed pricing strategy analysis shared in this piece. Pricing strategy may be difficult but its sure an important part of long term business strategy.

The various approaches that can be implemented by businesses to create prices for subscription products are welcoming. However, I will prefer A/B Testing strategy because it is more practical!

I left the above comment in kingged.com as well

Hi Alex,

Thank you very much for sharing your post on Constructing Pricing Strategy for Subscription Products.

You’re right when you said that pricing strategy is hard, it’s of utmost importance, and putting effort into optimizing it is well worth it – “a 1% improvement in price would increase operating profit by 11%, making it the most effective thing you can tweak for increased business performance.”

So yeah, it’s well worth it. Your post shows very simple and practical tips that anyone who have little to no knowledge on Constructing Pricing Strategy for Subscription Products will be able to have a couple of things to consider on doing after reading your post.

Looking forward to more posts like this from you, keep up the great work!

I left the above comment in kingged.com as well

Thanks, glad you liked the article, and good luck with your pricing strategy!

Cheers,

Alex

I really liked how this post shared a range of ideas, and in particular looked at how speaking to customers is the best method to figure out pricing. The qualitative response to ‘my price is X’ quotation was also golden.

I think this post would be even more awesome if it shared the following simple explanation as to why the first two methods are nice academia, but not useful in the real world :

http://customerdevlabs.com/2013/11/05/how-i-interview-customers/

(No, I’m not affiliated with that site, just a fan.)

Totally agree. I was talking to Dr Rob Balon, a market research/stats Phd, about the article, and he said the methods from academia are great – in theory. But they all have a flaw and that is volition.

As he told me, “It’s why political polls can have so much variance. Truth be told: many times voters really have no idea for whom they will vote: until the drapes of the voting booth close.

Consumers can demonstrate similar patterns regarding pricing research.”

We might indeed have to write a follow up article around that.

Cheers,

Alex

This is a killer article Alex! Thanks for sharing all the options available and including the pros and cons of including a short free trial period as part of the “price strategy”. Bookmarked.

Very informative summary, thanks for this

I’m curious about strategies like the von Westendorp – how many potential users would you need to collect responses from in order to achieve some statistical significance?

Thanks!