One of the testing strategies is experimenting with the path people take towards their final conversion/purchase. This is referred to as a split-path test or alternative path test.

This could give you the needed lift when nothing seems to move the needle anymore.

Table of contents

What Is a Split-Path Test?

A split-path test is defined as “a type of A/B/n test where, instead of just altering a single page, you change multiple sequential pages.”

Split-path testing sends users down a different path instead of showing different page variations. It includes things like multi-step checkout paths, multi-page forms, and product recommendation wizards. As Chris Goward explained in You Should Test That!:

Chris Goward:

“Alternative path testing allows you to maintain consistency of design elements throughout the path and change the number or sequence of steps. In a simple example, if you were to test a checkout path and wanted to test the button color in the car, you would change the buttons on all pages in the checkout to match. Alternatively, testing individual pages would produce inconsistency throughout the path that could decrease sales and outweigh any improvement from the change.”

While split-path testing isn’t talked about as often as your regular A/B/n tests about button colors, it isn’t a new concept. Bryan Eisenberg and John Quarto von Tivadar wrote about this a while ago in Always Be Testing:

“This is different in that you’re testing the performance of grouped pages against other grouped pages. For example, you could test a checkout process by splitting it into two variations, one with four steps (or pages) and another with only three steps.”

How User Flow Affects Conversions

A major factor affecting your conversions is user flow. It’s the path a user follows through your website interface to complete a task (make a reservation, purchase a product, subscribe to something). It’s also called user journey or conversion path.

Here’s an example of a typical conversion path you might have:

Facebook update –> Landing page –> Shopping cart sequence –> Payment funnel –> Pre-bill order confirmation page –> Billing page –> Confirmation page

Split-path testing is one way of optimizing your conversion path. As for why it’s important to do so, here’s how HubSpot explains it:

Just as it’s vital to make sure you’re maximizing the output of each individual page on your website, it’s incredibly important to understand how all of your pages work together. Which pages of your website make you the most money? Which ones generate the most leads? Which ones are preventing your prospects from advancing through your sales funnel? On a relay team, you can put together the greatest four runners in the world. But if they drop the baton at every handoff, you’ll never finish a race. Similarly, if a reader moves from one page to the next and gets confused, the only button they are likely to click is “back”.

Though Andrew Anderson, Head of Optimization at Malwarebytes, explains that assumptions about the drop-off between the user flow can limit the scope of your testing program:

Andrew Anderson:

“Conversely there are times where pages not matching are beneficial. It can be a huge benefit and also a massive risk to jump directly into assuming a full flow. It doesn’t have to at the start of the journey, you can test individual components and then view the impact of the system as a whole by doing a full path test. There are times that the “hand off” can be losing efficiency, but assuming so can be extremely impact limiting. Testing individual components and the whole allows you to see how much those assumptions about consistency really matter.”

Testing alternative conversion paths can open up new opportunities to boost conversions that cannot be obtained by simply changing page elements.

How Split-Path Testing Can Optimize Conversion Paths

Setting up split-path tests is similar to your regular old A/B/n tests in that you’re tracking the same goal. Each group of pages is treated as variation to be tested against the control, and each variation has the same conversion goal page – probably the order confirmation or thank you page.

You need to analyze the data the same way as a regular A/B test, with the same statistical rigor.

In addition, be careful with selection bias in split-path testing. As Andrew Anderson explains, many people think that you should only split-path test with new users, which creates a biased population:

Andrew Anderson:

“There is an extremely naive view that you should only test split paths on new users only as the complete change is supposed to be a major problem for existing users. This however assumes that those existing users are not people you care about or hope to make money from in the future, because eliminating them creates an extremely biased population and can invalidate your results.”

Remember also that site navigation isn’t usually linear. That means that gravity doesn’t pull visitors very cleanly down your funnel, no matter how much you wish that were the case. Linear assumptions of data is common, and it’s a bias that can be detrimental to any of your optimization efforts.. As Eisenberg and Quarto-vonTivadar explained:

“Although this can be an easy way to test strongly linear scenarios, you should keep in mind that few visitors navigate your site in a truly linear fashion (even though you might wish they did for analytics-tracking purposes!). Persuasion instead tends to occur along nonlinear paths, although that is a subject far beyond the scope of this book. Further, the longer the “click distance” between testing page and conversion page, the greater the likelihood that some visitors will wander off to other portions of your site, which Website Optimizer may record as a failed conversion for testing purposes, even though such a result doesn’t reveal visitor intent.”

For that reason, split-path tests are most appropriate on sections of your site that do follow a linear path, like your checkout flow and registration forms.

Split-Path Testing is An Innovative Test

Split-path testing is considered an ‘innovative test’ – as opposed to an incremental test, split-path testing offers offers the opportunity for much greater lifts. That said, it’s riskier as well for multiple reasons.

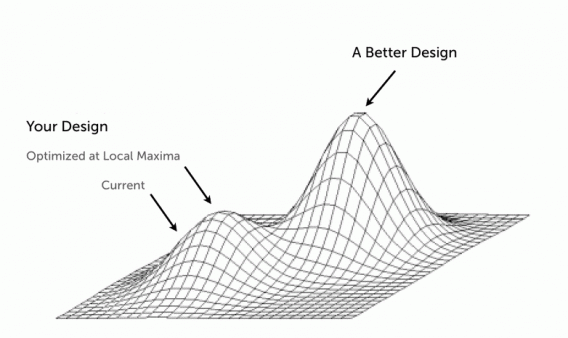

As Andrew Anderson mentioned, “Perception is not always reality however as you may just be exponentially adding bias on top of bias and allowing yourself to take more time and opening yourself up to even more local maxima.”

If you’ve hit a glass ceiling (i.e. a local maximum) and need to do something innovative and creative to bust out of it, split-path testing is a possible but highly cost inefficient solution.

Let’s Talk About The Local Maximum

What is the local maximum?

It’s when, after a progressive period of A/B/n testing, your gains start to slow down. You’re experiencing diminishing returns even though you’re testing a bunch of iterations. It’s frustrating, but it happens to everyone.

What can you do about it?

There are many solutions, but most of them center on shifting your paradigm and getting a bit creative. In other words, swinging for the fences with some innovative tests, trying to change customer behavior/experience to increase conversions.

Though, as Andrew Anderson explains, split-path testing is not a silver bullet solution to the local maximum problem:

Andrew Anderson:

“This is almost always a sign of poor test discipline and a lack of creativity, and sometimes thinking about a different problem, the entire path, helps give temporary relief to that problem. That being said it is never a full solution to the problems of bias and storytelling.”

Split-Path Testing Subscription Pathways

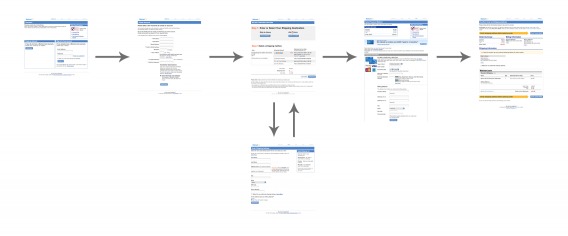

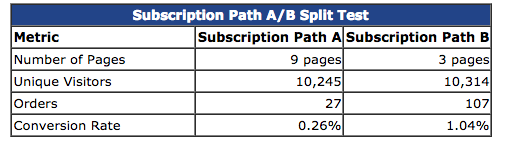

Marketing Experiments wrote about a few tests they ran optimizing the subscription funnel of some large publications. They performed split-path testing to simplify the funnels. Here’s what the first test looked like:

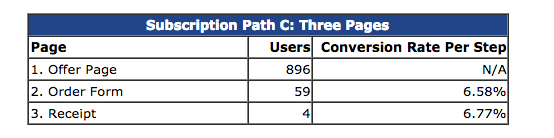

In this case, reducing the steps from 9 to 3 increased conversion rates by about 300%. As they wrote, “Reducing the number of steps is probably the single most-significant improvement you can make to your subscription path.“

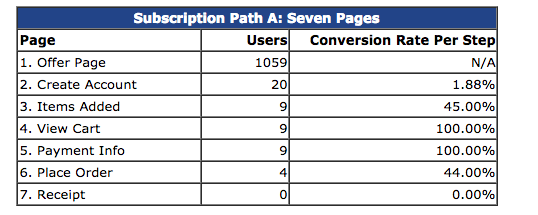

In their second example, they employed a similar strategy: reduce steps to subscription. This is the flow that they started with (resulting in zero registrations in this case):

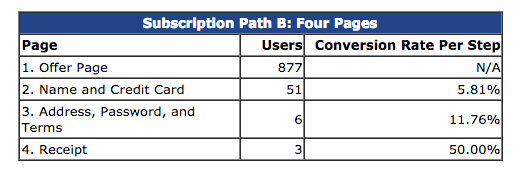

They decided to chop a few of those pages off and pair it with an email capture form on the initial offer page for the next test:

Finally, they removed another page from the sequence while retaining the same offer page:

Of course, their sample size is too small to draw any conclusions between the four page and three page examples, but it seems they are moving the flow in the right direction.

Add Registration Steps

You can also take the opposite strategy and add in more steps to the checkout funnel. Here’s Andrew Anderson’s take:

Andrew Anderson:

“Keep in mind that adding more pages can also increase performance. A very large customer I worked with had a very strong inverse correlation between the pages a user viewed and the revenue they spent (more pages meant more money). When you swing big, it is even more vital that you challenge your assumptions, meaning that the cost goes up exceptionally high, as does the possible reward.”

So, let’s say you’re running a SaaS startup and want to increase the amount of paid signups you have. Your optimization efforts have leveled out – value proposition tweaking is no longer bringing any results. So you think that perhaps you can increase quality leads by changing the checkout flow itself.

You go from: Home page → Sign up → Confirmation page

To: Home page → Features → Sign up → Confirmation page

You hypothesize that if customers are to view your features page before being asked for their credit card, they’ll be more likely to sign up. Perhaps they’ll be higher quality leads. They may have a lower attrition rate. So, you can split-path test this to be sure.

Change The Order of Steps in a Funnel

Sometimes, changing the order of the flow but keeping the same content can provide a lift (Andrew estimated that he’s seen anywhere from 5-45% lifts and for some reason the scale tends to go up with larger sites.”

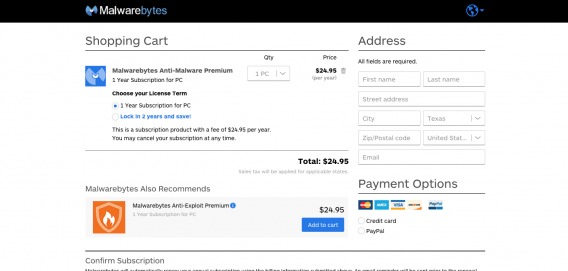

So imagine you’re selling a subscription product and your checkout flow looks like this:

Home page → Sign up → Payment Page → Create Account → Thank You

You could try changing the order to switch the payment and the create account pages, like this:

Home page → Sign Up → Create Account → Payment Page → Thank You

Similarly, if you ran an eCommerce site, you could experiment with running the billing address before the shipping, or vice versa. You get the picture.

Andrew Anderson told me about a Malwarebytes example where they ran a test changing their entire shopping cart user flow, going from multiple pages to different orders and page layouts. They tested a large variety of examples and found that moving from a 3 page flow to a one page flow and introducing the purchaser information fields much earlier results in a dramatic uptick in overall user RPV.

Test Low Touch vs High Touch Paths

Another split-path test one could run is sending users down a fully online purchase path or a live representative quote or demo path.

Picture that you’re running a SaaS company that sells form analytics software. You send 50% of traffic down your traditional funnel where they can pay online and get started on their own, and you send 50% down a “get a quote” or “get a demo” path and have a sales rep take it from there.

In this scenario, you need to factor in the increased cost that accommodates the increased workload for your sales team. Here’s how Andrew Anderson put it:

Andrew Anderson:

“Keep in mind that at this point you need to measure true net RPV as the cost dramatically goes up at that point. That being said I worked once with a financial lead gen company that tested this and had a 24% net RPV gain by forcing people to talk. Fewer leads but much higher cost. Conversely at Malwarebytes we have found the exact opposite. The more we try to move people away from talking to our B2B reps, the less money we make and it is dramatic (and also a -.81 correlation).”

In general, the sales rep/quote approach tends to work better with more complicated or more expensive products (this is the norm for many enterprise software products).

In this case, as in the others, there’s always a chance it won’t work and you’ll have spent a large opportunity cost. In addition, mind your sales cycles and your churn later on down the line with either path.

Warning: Heavy Development Resources Might Be Required

Split-path testing has promise of a huge lift but also the possibility of a huge waste of time.

For instance, coding these variations is much more costly and time consuming than testing page elements. Developers need to code outside of their testing tool and usually run split url tests to accomplish this (could also run multi-page tests for some checkout flows, but that’s theoretically different from the type of split-path test we’re talking about).

Dave Gowans, Head of Conversion at Conversion.com, gave the following example:

Dave Gowans:

“The biggest challenge for Alternative Path testing is the amount of development work that goes into the tests. Whether you build an alternative version of the funnel in the backend or using a testing tool, the development effort multiplies with the number of pages involved, so you could end up spending many days of time, even for a relatively small design change.

For one client, an online pharmacy, we spent hundreds of hours building a complete re-skin of their funnel to match a new design on a single page. It showed almost no impact on the overall conversion rate. That time could have been much better spent on other, smaller, tests delivering more impact.”

And as Andrew Anderson said, “You almost always need a unique user flow path or a cookie based system to control server side implementation. In many cases you will not even use the testing tool for data tracking.” It’s a minor issue, but one to consider with split-path testing.

Just imagine that you need to have a developer work on your variation full time for two weeks. How much does that cost you in time and opportunity cost (what else could they have built in that time)? Andrews says you can mitigate some of this cost by never wasting the time on 1 alternative experience.

According to him, “2 wasted weeks as a 10% success rate is far worse than 6 weeks at a 75% success rate and a 50-100% increase in expected scale of outcome. If you are going to go this big and take the time, the math always shows that you need to do even more experiences. The cost does not exponentially grow but the expected outcome does.”

Another issue: the only data you have is current funnel performance, meaning that existing analytics (correlative data) is basically useless. It tells you what did happen, no what should happen.

A Possible Split-Path Testing Strategy

Being that there is great risk with split-path testing, here’s a possible strategy to consider:

Start by improving your existing funnel. Use the ResearchXL model to figure out all friction, distraction, and other issues. When you begin to hit diminishing returns, then it may be time to experiment with split-path testing. By testing whole flows you can actually get better data, in that you’re able to find real problems and distinguish them from data anomalies and/or biased perceptions.

Finally, when considering split-path testing, keep in mind how you’re prioritizing tests. With this type of test, you’re balancing the impact with a much higher cost of implementation. Therefore, with the higher risk associated, you always need to increase the expected outcome. Dave Gowans from Conversion.com echoed this sentiment:

Dave Gowans:

“Our advice is to always carefully evaluate the impact and ease of every test – putting the effort into spending time with your developers, understanding the most effective way to make the change and how many hours it will take. This small investment of time upfront is easily justified by the time you’ll save by not embarking on a infeasible project. Look closely at the impact of your proposed test (both the upside and the potential downside of not testing a change). Does it really make enough difference to test it?”

Conclusion

Split-path testing runs on the same statistical models as a regular A/B/n test, but is different in that it fundamentally changes a user experience.

It is both a potential huge win but also an opportunity to get even more caught up in your own biases. It is the definition of swinging for the fences, but if you do it with discipline and with an understanding of opportunity cost and efficiency, it can be a huge win for your entire organization.

This could be good, in that you can achieve bigger uplifts, or this could be bad in that you spend a lot of money and time and development resources on a test that doesn’t move the needle at all.

Alex, thanks for the article! Split path test is something new to me. It is obvious that this type of testing requires a higher level of dedication and technical efforts. This might keep many key decision makers from starting it. Testing separate elements is easier to implement and much cheaper in fact. Besides it is also true that implementing basic rules is more likely to be successfully. For instance, so far I was sure that reducing steps during of the funnel is almost a golden rule; this is why I was greatly surprised to hear about the opposite results. Articles at Conversionxl are always backed up by real life data/examples and I highly appreciate the knowledge you share.

Cheers,

Alex

Thanks for your comment, Alex. Glad you’ve been enjoying the blog. Nothing works all the time, reducing funnel steps included.

Cheers,

Alex

Totally agree with you Alex, super important to evaluate before taking risks by applying models and frameworks into the testing strategy. Thank you for putting this together.

What about testing testing lesson flow in CMS? Would split path testing be appropriate? What would change in this scenario?