Think it’s tough to earn links or shares for your content? Try earning money.

For publishers, doing so is a push-pull between discoverability and monetization. News sites have long been at the forefront, but plenty of speciality sites (e.g., The Athletic, Cook’s Illustrated, Adweek) have paywalls, too.

Search engines are vital for discoverability. But, historically, they’ve undermined monetization—requiring crawler access that savvy users exploit and demanding free clicks for searchers.

The hard part isn’t making it functional but profitable. Indeed, if you want to find out whether anyone really cares about your content, just put up a paywall.

Table of contents

What are paywalls?

A paywall is a restriction that acts as a digital gate that controls access to content for which you need to either pay or become a subscriber. It’s used by companies to hide information behind a gate, encouraging them to sign up for branded content or pay in order to access the content.

What is the effect of paywalls on SEO?

Google’s guidelines have changed over time, but they’re built around the needs of news publishers and hold fast to a central tenet: Google cares more about providing the best information than whether that information is behind a paywall.

Google’s Public Search Liaison Danny Sullivan has openly pushed back against those who want subscription-only content flagged in search results:

Experiments run by Dan Smullen, who manages technical SEO for Independent News & Media, demonstrate that Google isn’t biased against paywalled content:

Before launching our paywall in February, we implemented a soft wall—a registration wall. We tested this on two completely temporary replicas of our sites for Canada (independent.ie/ca/) and Australia (independent.ie/au/).

For users in those countries, we put all content behind a registration wall. We saw less than a 5% drop in traffic over a six-month period but a considerable amount of new registrations.

We also tested putting a randomised 50% of all pages in our travel section (with an average position of 1–5 in Google Search Console over a 3-month period) behind a registration wall. The travel section on Independent.ie was selected due to its ranking for evergreen queries, such as “things to do in Canada.”

We saw no significant decrease in average ranking. Currently, Independent.ie is still #1 on Google.ie in Ireland—despite being behind a paywall.

Still, as Barry Adams of Polemic Digital told me:

If Google has to choose between a gated piece of content and a free piece of content that have roughly the same quality signals, Google is always going to rank the free content first—because it’s a better user experience.

In addition to those underlying principles, there have been two seismic shifts: First Click Free and Flexible Sampling.

First Click Free (2008)

Google announced its First Click Free (FCF) policy in 2008, requiring publishers to:

allow all users who find your page through Google search to see the full text of the document that the user found in Google’s search results and that Google’s crawler found on the web without requiring them to register or subscribe to see that content.

For publishers, the policy didn’t work. Anyone who accessed an article via a Google search enjoyed Infinite Clicks Free. In 2009, Google allowed publishers to cap FCF views at five articles per day; in 2015, the cap tightened to three articles.

The changes didn’t solve the issue. Access to three articles per day—still as many as 93 articles per month—sated most users. Additional devices were a multiplier: A phone, tablet, work computer, and home computer meant 12 articles per day, or 372 per month.

By early 2017, some publishers had had enough. The Wall Street Journal opted out of FCF in February after a partial opt-out in January “result[ed] in subscription growth driven directly from content.”

(An alternative to participating in FCF, a “subscription designation,” allowed Googlebot to crawl an 80-word snippet of an article, which served as the sole source of ranking material.)

Other publishers had similar issues, as Taneth Evans, Head of Audience Development at The Times in London, detailed:

There were too many flaws with the model to participate, so the business opted out. As such, Google continued to get stopped at our paywall during crawls, and we became virtually non-existent in its search engine results pages.

Google ended FCF in October 2017, shifting the responsibility of metering and experimentation back to publishers.

Flexible Sampling (2017)

Even as Google dismantled FCF, it contended that publishers should provide some free content. What changed was who was in charge of defining those limits:

We found that while FCF is a reasonable sampling model, publishers are in a better position to determine what specific sampling strategy works best for them [. . . ] we encourage publishers to experiment with different free sampling schemes, as long as they stay within the updated webmaster guidelines.

Flexible Sampling, still in place today, offers publishers two options:

- Metering. “Provides users with a quota of free articles to consume, after which paywalls will start appearing”;

- Lead-in. “Offers a portion of an article’s content without it being shown in full.”

In both instances, search engines have access to the full article content—either in the HTML or within structured data—while user access is restricted.

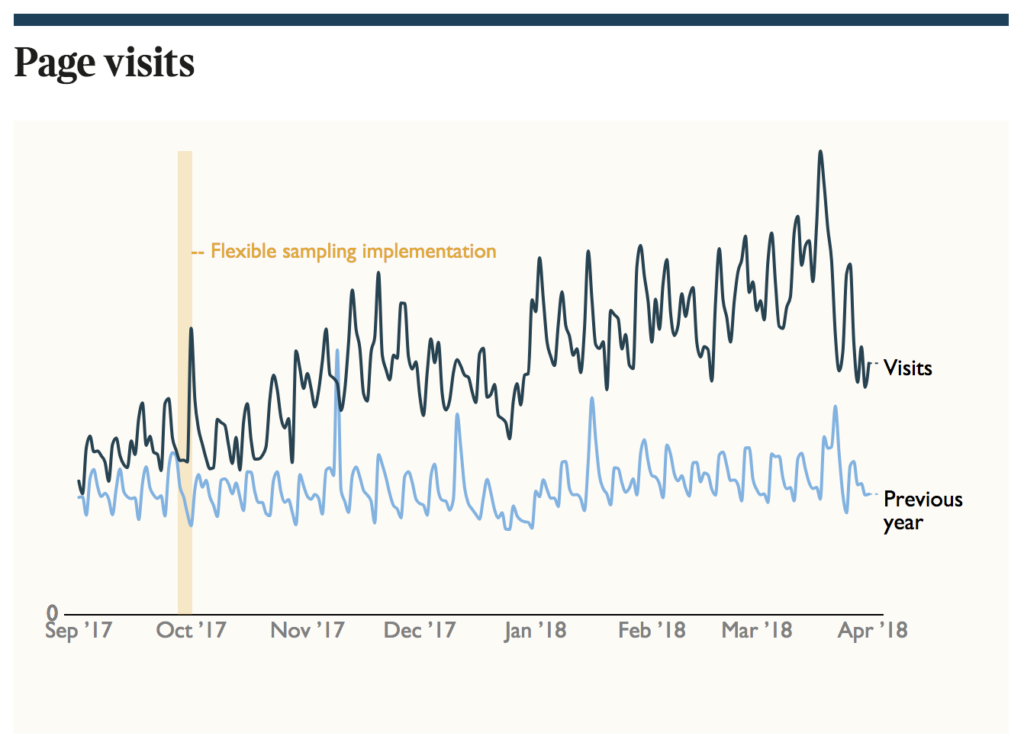

For sites like The Times, the change resurrected their participation in search:

From those two core variations—metering and lead-in—come an array of hybrid possibilities (e.g., showing users lead-ins after metering expires, making some content fully free and other content lead-in only, etc.).

A third option, of course, is a hard paywall—denying all access to searchers or searchers and crawlers. Which system—or any system at all—makes sense is up for debate, and experimentation.

Metering vs. lead-in

Paywalls, by default, are a barrier to organic acquisition—they stop some users from accessing some content. Many sites adjust that barrier with metering.

Metering

“As far as Google’s concerned,” explained Adams, “metered sites are free websites. Googlebot looks with a clean session, so Google is perfectly fine as long as the first click is freely visible.”

While publishers ultimately control how many free clicks a user gets before hitting a metered paywall, Google has recommendations:

- Use monthly (rather than daily) metering.

- Start with 10 monthly clicks.

Publishers are free to experiment, as, historically, WSJ aggressively has.

Google’s own research, done “in cooperation with our publishing partners,” showed that “even minor changes to the current sampling levels could degrade user experience and, as user access is restricted, unintentionally impact article ranking in Google Search.”

Google offers a relative threshold for that “degraded” user experience:

Our analysis shows that general user satisfaction starts to degrade significantly when paywalls are shown more than 10% of the time (which generally means that about 3% of the audience has been exposed to the paywall).

So, in theory, a pile-up of users hitting your paywall could affect rankings. But is Google carefully monitoring (notoriously noisy) clickstream data to paywalled sites?

Probably not, according to Matthew Brown, a consultant who previously managed SEO for The New York Times:

You’d have to get really aggressive with metering to see a significant negative ranking impact. But you can imagine a scenario with limited metering (e.g., one click per month) in which most users pogostick after hitting a paywall—a bad user experience that, it’s hard to imagine, helps rankings.

Metering does allow sites to segment users who hit your paywall—a key audience for conversion optimization. Google endorses that strategy of variable, user-specific metering:

By identifying users who consistently use up the monthly allotment, publishers could then target them by reducing the sample allowance for that audience specifically, and, by allowing more liberal free consumption for other users, reduce the risk that overall user behavior and satisfaction is degraded.

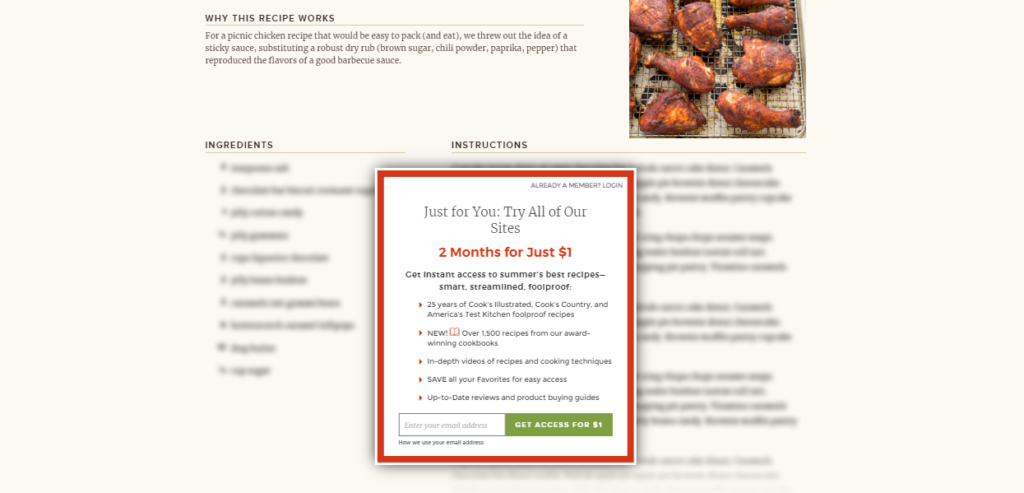

For sites that rely on a lead-in, it’s a different conversation.

Lead-ins

Metering and lead-ins aren’t mutually exclusive. Google even recommends using lead-ins for users who’ve hit a metered paywall:

By exposing the article lede, publishers can let users experience the value of the content and so provide more value to the user than a page with completely blocked content.

Lead-ins can also restrict access immediately or restrict access to a subset of site content (i.e. a freemium model).

From a technical standpoint, metering is simpler—search engines can always access the full content of the article in the HTML. Lead-ins must provide search engines access while also keeping freeloaders from exploiting loopholes.

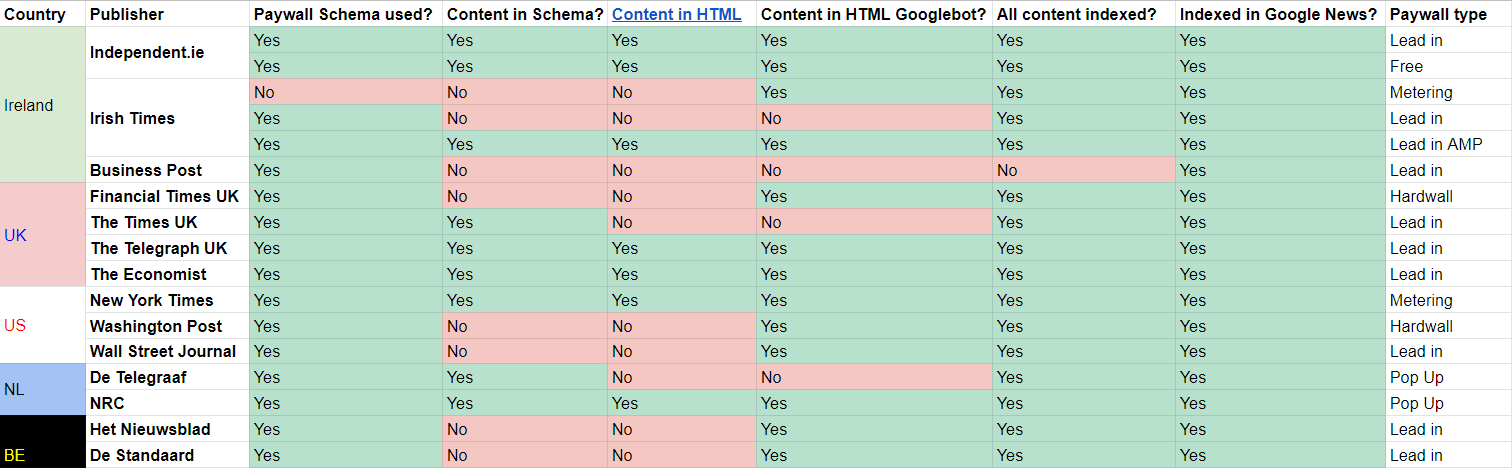

Smullen identifies two types of lead-in models:

- Lead-ins with content in HTML or structured data for Google and users;

- Lead-ins with content in HTML or structured data for Google only.

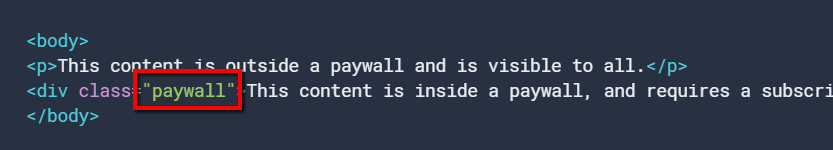

1. Lead-ins with content in HTML or structured data for users and Google

A standard lead-in offers a short paragraph followed by a subscription form:

If you load that article into Google’s Structured Data Testing Tool, however, the entire article is in the body copy of the Article schema. This method helps Google crawl paywalled content that users can’t see.

For example, in that article, this sentence is present only in the structured data: “The Longstaffs have given hope, but only if they stay, only if more follow in their promising footsteps.”

That text can’t be found in the HTML using an HTML viewer:

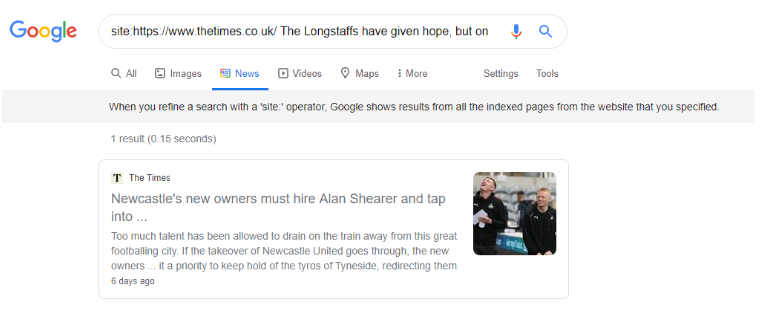

But if you perform a site: search for it, Google has no issues indexing content found only within the structured data:

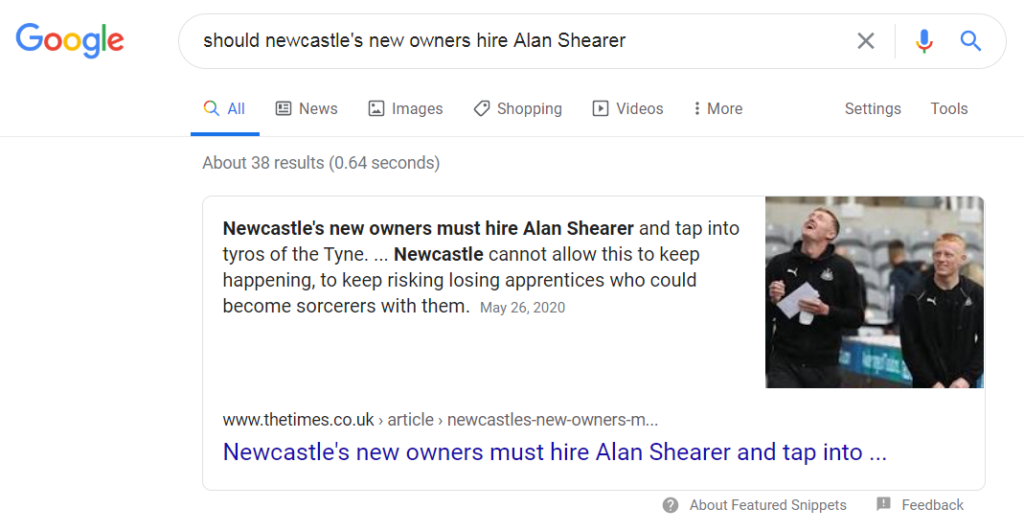

That content, controversially, can even show up in a featured snippet, as this example does for the query “should newcastle’s new owners hire Alan Shearer”:

The upside of this approach—from a non-SEO point-of-view—is that URLs can’t be loaded with HTML viewers, making content less vulnerable to scrapers.

However, as just shown, anyone willing to go the extra step of extracting content from the structured data can do so—hence the second method below.

2. Lead-ins with content in HTML or structured data for Google only

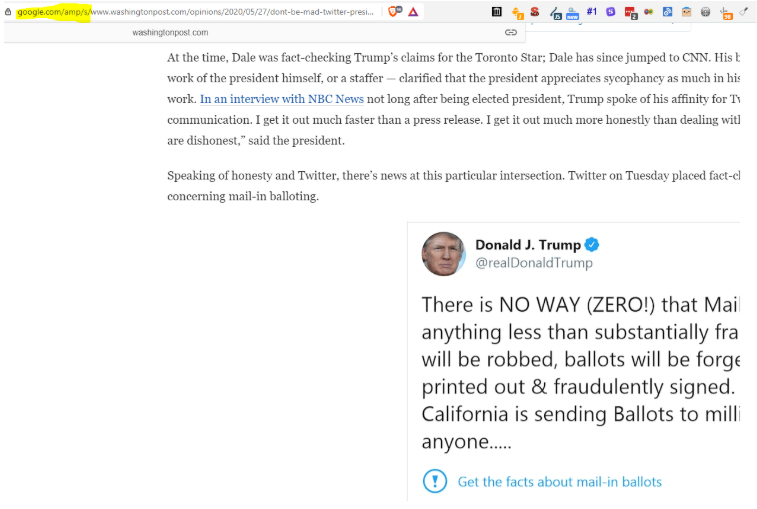

If you take a random article on The Washington Post and load it into Google’s Mobile-Friendly Test, you can see that Google has no issue crawling or rendering the content:

That’s because the Google Mobile-Friendly Test uses the real Googlebot user agent and IP.

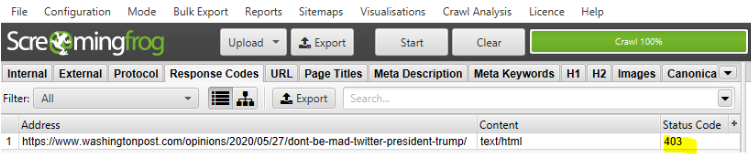

If you try to replicate that with a crawler, such as Screaming Frog, you’ll get a 403 Forbidden response code because Screaming Frog only spoofs Googlebot. (You can verify the real Googlebot for your site.)

So, yes, if someone really wants to read the article for free, they can copy the HTML from the Mobile-Friendly Test and load it into an HTML viewer.

But this method better protects publishers against scrapers since the Mobile-Friendly Test would limit the volume of requests. Unless a requester is the real Googlebot, the content isn’t scrapable en masse.

The downside of this method—if you use AMP—is that the article can be read on Google’s AMP cache.

Indeed, there’s no shortage of ways to bypass paywalls.

So how do you keep the freeloaders out?

“If someone wants to circumvent a paywall,” says Adams, “they’ll find a way.” He continues:

Don’t make it too technically complex. For maximum adoption, make it a little more difficult. But, more importantly, make sure that it’s frictionless to sign up, and once you’re signed up, it stays entirely frictionless—so people never feel bothered anymore.

Complexity adds more risk than benefit. “You might be able to squeeze another 1–2% of freeloaders into paid subscribers,” suggests Adams, “but how much will you piss off everyone else?”

Most of us have, at some point, cleared our cache or cookies to reset our metering on a site. And metered sites with “sophisticated” systems to keep out freeloaders (e.g., The New York Times) can be undone simply by disabling JavaScript.

Chrome developers continue to play cat-and-mouse with publishers on Incognito mode. Each time they publish an update to fix the “bug” that lets publishers block Incognito users, someone finds another workaround.

Your time is better spent making sure search engines can crawl your content.

Technical SEO implementation for paywalled content

Search engines have to crawl your content to index it. Paywalls, of course, restrict access—to humans and, potentially, crawlers.

On top of that, if you show different content to humans and crawlers (to help crawlers index your full page while restricting visible access) without a proper SEO setup, your site may get flagged for cloaking.

Avoiding cloaking

Google worries about cloaking because it causes Google to index your content for what you show it (e.g., healthy living guide), but users see other information (e.g., hard sell for diet pills).

The March 2017 Fred update unintentionally demoted some legitimate paywalled sites as Google cracked down on cloaking. As a result, Google developed structured data to denote paywalled content.

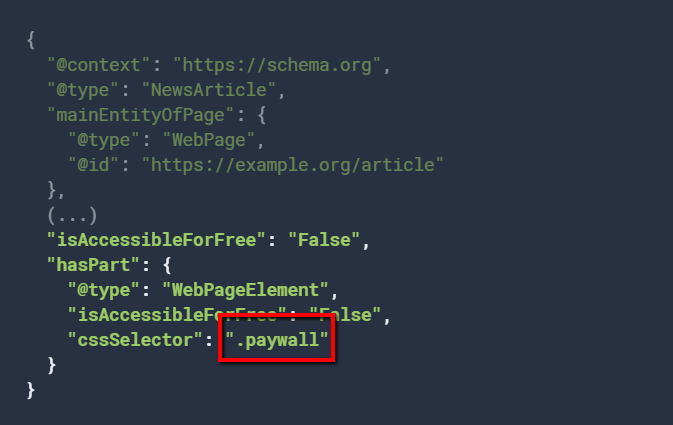

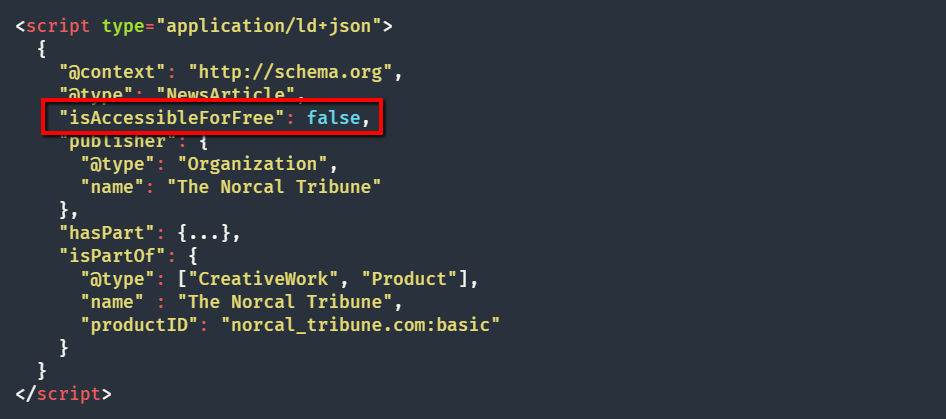

Structured data for paywalled content

Google has clear guidelines on structured data for paywalled content:

- JSON-LD and microdata formats are accepted methods.

- Don’t nest content sections.

- Only use .class selectors for the cssSelector property.

This markup is supported for the CreativeWork type and subtypes:

- Article;

- NewsArticle;

- Blog;

- Comment;

- Course;

- HowTo;

- Message;

- Review;

- WebPage.

Multiple schema.org types are allowed (e.g., “@type”: [“CreativeWork”,”Article”,”Person”]).

To keep Google from showing the cached link for your page, which allows freeloaders access, add the “noarchive” robots meta tag.

Accommodating AMP

In May 2020, Google announced that publishers no longer had to use AMP to appear in the Top Stories section, starting in 2021.

For many news publishers, the Top Stories carousel accounts for the bulk of organic traffic—as much as 80–90%, according to Adams—making AMP accommodation essential.

Because timeliness is paramount—stories have a maximum shelf life of 48 hours—Google doesn’t have time, Brown explains, for more in-depth analysis:

News-specific ranking algorithms are considerably less sophisticated than general web ranking algorithms, so they’ll use simplified things like drastically lower CTRs, increased bounce-backs to search, and lower dwell times.

These are things they can measure simply and use significant outliers to identify user satisfaction issues.

Documentation for AMP is based on the amp-subscriptions component, which adds features on top of amp-access, notably:

- The amp-subscriptions entitlements response is similar to the amp-access authorization, but it’s strictly defined and standardized.

- The amp-subscriptions extension allows multiple services to be configured for the page to participate in access/paywall decisions. Services are executed concurrently and prioritized based on which service returns the positive response.

- AMP viewers are allowed to provide amp-subscriptions a signed authorization response based on an independent agreement with publishers as a proof of access.

- In amp-subscriptions content markup is standardized allowing apps and crawlers to easily detect premium content sections.

AMP adds a challenge for publishers who want to show content only to logged-in users because “AMP can’t pre-fetch whether someone is a subscriber or not,” explains Smullen, “which is probably why they’re very interested in offering their own subscribe with Google product.”

If you publish AMP content and want to appear on Google search, you must allow Googlebot in, note Google’s AMP guidelines: “Make sure that your authorization endpoint grants access to content to the appropriate bots from Google and others.”

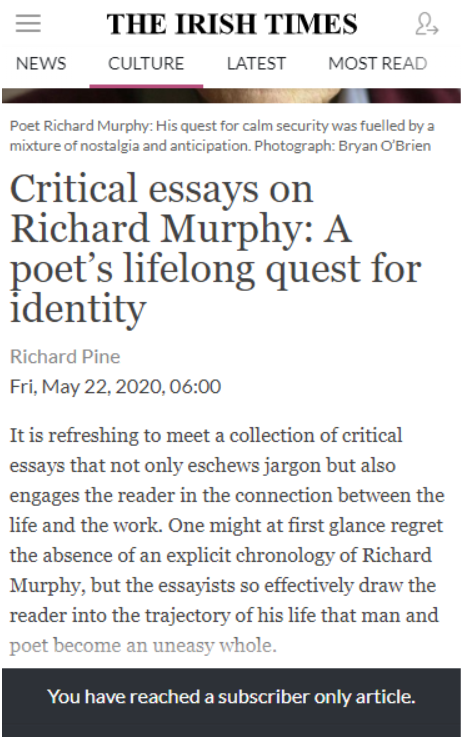

As Smullen discovered, this led The Irish Times to deploy an interesting paywall method. A snapshot of their split of paywalled articles shows that about 10% (7/71) of homepage articles are “subscriber only” or use a hard paywall, which suggests that their primary method to encourage subscriptions is metering (since 90% of articles are openly available).

But they also use a hard lead-in approach for their subscriber-only articles. When viewing these articles on desktop or mobile, the article body text is removed from the HTML. They use a temporary redirect to push users into a hard paywall:

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/critical-essays-on-richard-murphy-a-poet-s-lifelong-quest-for-identity-1.4246452

302s to

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/critical-essays-on-richard-murphy-a-poet-s-lifelong-quest-for-identity-1.4246452?mode=sample&auth-failed=1&pw-origin=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.irishtimes.com%2Fculture%2Fbooks%2Fcritical-essays-on-richard-murphy-a-poet-s-lifelong-quest-for-identity-1.4246452

However, if you inspect the source and identify the AMP alternate…

<link rel="amphtml" href="https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/critical-essays-on-richard-murphy-a-poet-s-lifelong-quest-for-identity-1.4246452?mode=amp">

…then load that page into the Mobile-Friendly Test and, finally, paste the HTML into an HTML viewer, you can access the full article. The HTML is in the HTML page source for the real Googlebot.

So, subscriber-only articles restrict the content in the HTML and structured data for everyone except Googlebot—even within AMP content.

Smullen sees their strategy as a clever stretching of Google’s recommendations. Their hybrid model allows them to encourage subscriptions from metering but also restrict Incognito users, HTML viewers, AMP users, and scrapers from their subscriber-only content.

The only downside is error warnings of content mismatch in Google Search Console.

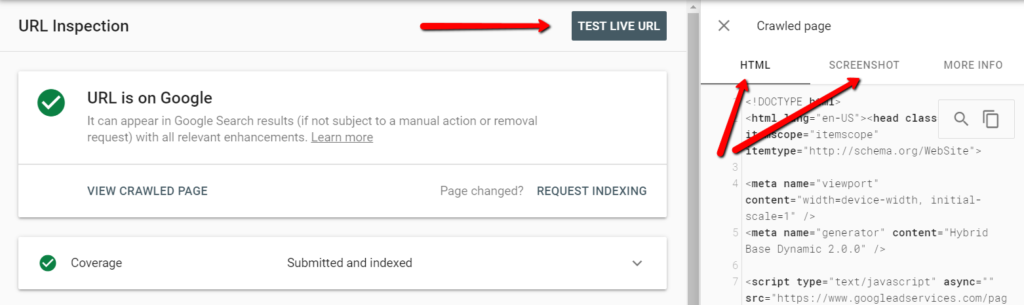

QA’ing your implementation

Google’s Structured Data Testing Tool shows if your structured data implementation is correct, but you may also want to see the render—if your implementation, while error free, also displays what you expect.

You can do that using:

- Google Search Console;

- Google’s Mobile-Friendly Test.

“Technically,” Adams told me, “there’s always a way to build it. It’s more about whether it makes business sense.”

How to make a paywall profitable

“The websites I’ve seen work,” Adams said, “either focus on quality or quality and a specific niche.”

Smullen agrees: “Real stories, fact checking politicians, investigative journalism, exclusive interviews, and explainers on what the headlines mean is what people are willing to pay for.”

Editorial behavior lags behind that realization. Smullen again: “Most broadsheets and tabloids are free because online, traditionally, was a ‘digital dumping ground’—an afterthought.”

The long-term impact of that neglect has become more costly as it’s gotten harder to monetize pageviews.

Monetizing pageviews isn’t enough

As popular as news sites may seem, Smullen explains, they’re small fish in search:

Mel Silva, Google’s managing director for Australia, said that news accounts for barely 1% of actions on Google search in Australia, and that Google earned only AU$10 million in revenue from clicks on ads next to news-related queries.

In addition, good journalism, such as fact checking politicians in an election, might not always be what drives pageviews—and also not what advertisers want to bid on—but is massively important for our society.

As Smullen concludes, “the fall of Buzzfeed and the rise of The New York Times suggests that the news subscription model is the only sustainable model left to publishers.”

It helps if you’re starting with a powerful brand.

Where are you starting from?

Building a brand new brand behind a paywall is tough, admits Brown:

The Athletic managed it by capitalizing on well-known local writers in each market who would bring an audience with them and meet the open-my-wallet criteria. It’s much tougher to try that without bringing an audience with you from the outset.

I doubt we’ll see a ton of current publishers adopt a new paywall strategy, even with Google’s efforts to relax guidelines. Too much of what they’re covering is still a commodity for most users, and unwinding the ad-supported model has a lot of friction.

You’re rewriting your business on speculation.

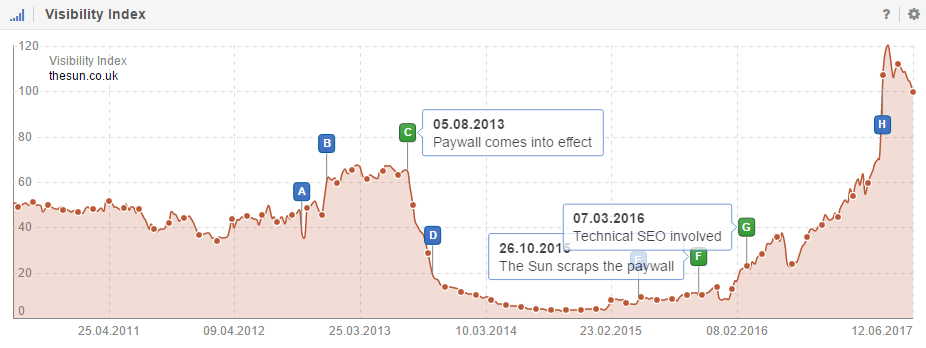

A speculative strategy can end in catastrophe, as Adams saw when he came in to rescue The Sun:

Paywalls can work for news sites, just not news sites that don’t necessarily have a strong USP in terms of the quality and type of reporting they do, which is why The Sun’s paywall was such a failure [. . . ] their content was very interchangeable with other websites.

If you go behind that paywall, you have to be fairly confident that you’ve built those quality signals over time—that Google can’t just throw out your website. If another website can pick up the slack, that’s going to happen.

News is an especially challenging vertical since no site owns a newsworthy event. The facts you publish may quickly become the source material for dozens of competing articles, something Smullen laments:

I see daily evidence, even for free stories, that regional publishers swipe the content and story from us, giving it a different headline and ranking in front due to their published time being more recent.

At the same time, organic traffic, for many news sites, isn’t the primary acquisition source, in part because most news-related queries are new and never searched before.

Smullen estimates that SEO accounts for 25% of sessions, some 70% of which are brand queries; his colleague at a Belgian news site reports organic traffic to be less than 10% of total sessions.

SEO requires backend considerations but doesn’t, in many cases, drive editorial strategy, says Smullen:

If someone were to build a paywall-worthy brand from scratch and get bogged down by domain authority metrics and traffic stats, they would never produce award-winning content.

Tapping into a niche, being subscription only, and getting in front of the audience you want—instead of the mass audience—may be a better way to get started than concerning yourself too much with the online authority of the big players.

Maintaining a balance between discoverability and monetization requires getting everyone onboard, as Brown explains:

One crucial strategy is to model out organic decline to the most severe point to gauge how comfortable everybody is with risking that traffic.

More often than not, this gives decision-makers serious pause, and in some cases has led to scrapping the paywall idea altogether. That’s probably for the best, as the worst paywall decisions are ones where half-measures and unrealistic expectations are in play.

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that some trends have shifted back in publishers’ favor.

Trends that just might help your paywall succeed

As Adams argues:

- People are increasingly willing to pay for quality information;

- Online payments are easier to process.

The New York Times, which passed 5 million subscribers in February and cleared $800 million in revenue last year, supports that opinion.

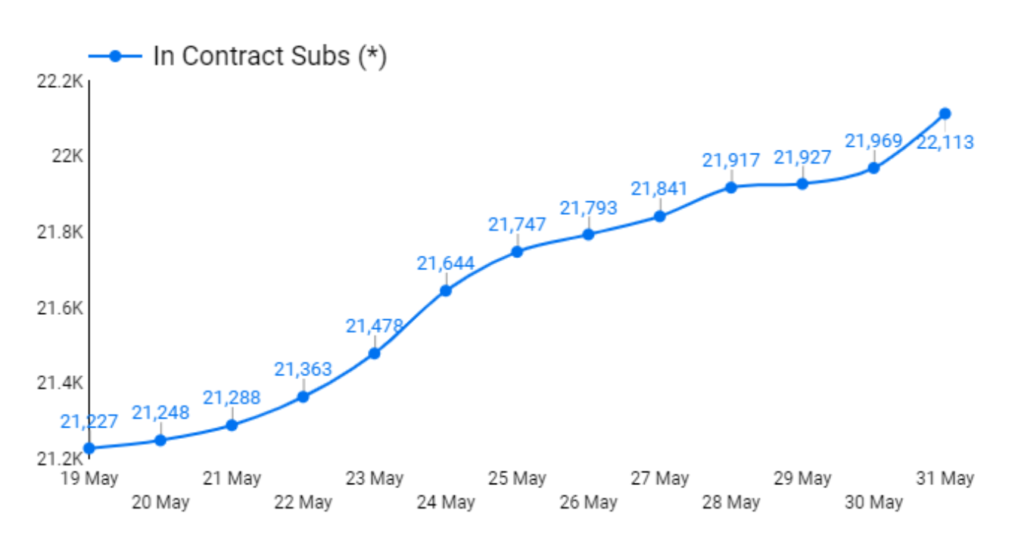

Since launching a paywall on Independent.ie in February, Smullen has seen strong, consistent subscription growth—from zero to 22,000 in three months:

Smullen’s experience—recent and over the long haul—has made him an advocate of a hybrid approach to paywall implementation. His strategy is specific to the news industry but has obvious parallels for other niches:

1. Free access for major news stories (e.g., a country announcing a lockdown) or free news, such as press releases or unessential news that every other publisher has (e.g., a fast-food company giving away free fries for the next 24 hours).

That type of content, Smullen says, gets great traction on social media and helps publishers monetize pageviews with ads.

2. Lead-in with a registration or subscription wall and an app conversion strategy. From a technical perspective, content isn’t visible to the user or random bots in the HTML or structured data.

When a specific search engine (e.g., Googlebot) accesses the content with a valid IP, however, it’s presented with the content in the HTML and has correct paywall structured data.

The strategy also allows publishers to deploy a “soft wall” to capture an email address from search and encourage users to download the app. After a certain number of articles per month, you apply a hard paywall.

App users are the most loyal users, according to Smullen. They also give publishers direct marketing potential with push notifications and newsletter subscriptions, all while secreting users away in a walled garden.

Finally, a deep-linking strategy can ensure that when a user discovers content via a search engine, they’re directed back to the app (similar to how The Guardian app works).

Conclusion

“It always boils down to the same conversation,” said Adams. “Are people going to pay for this? Are you unique enough or confident enough in your service offering that you want to put a paywall on it?”

Those are questions about your editorial and brand strength. If you don’t have the content to do it, you’re in trouble. The technical side, in comparison, is straightforward.

On the whole, the future of the publishing industry may not be as dire as it seemed a few years ago, when search engines gave away the store, consumers balked at paying for online content, and ad blockers ate away at revenue.

But it’s not easy. The Athletic recently laid off 8% of its staff. Whether that’s a sign of a dysfunctional model, insufficiently valuable content, or the current economic times is up for debate.

“If you’d asked me four or five years ago if a paywall was a good idea,” said Adams, taking it all in, “I would’ve said, ‘No.’”

But, he concluded, like any good SEO, “Now I’d say, ‘It depends.’”

Great Article Derek. I suffered a great loss while I was having paywalled content on my website since the SEO was not properly setup. Took me almost 2 months to understand the specifics to resolve the things.

Thanks, Gautam. Glad you were able to get it sorted out!

Great article nice information will definitely try it sometime

Thanks!

Wow, it’s very insightful Derek. I work for Theaustralian.com.au as head of audience growth and agree with everything you discussed. (https://www.linkedin.com/in/gudipudi)

Thought its worth mentioning my observation, during major events google tends to favour free sites(I have collected some stats and screen shots at the time of bush fires and coronavirus in March).

Having said that, our subscription numbers are very healthy and growing month of month and traffic from Google has doubled since 2018. If google was not biased particularly during major events- we would have experienced even higher growth.

By the way, we have a hard Paywall.

Thanks for sharing your experience—and glad to have more anecdotal evidence that paywalled sites can succeed, despite the challenges.

Very helpful article and I follow that as a new.