If I gave you a 750 page book and a 150 page book, which one would you guess to be the better (more valuable) book?

There’s not really a correct answer here.

You might think that because there is more quantity – it is more voluminous – that it is worth more because of the effort involved in creating it.

Or you may be time strapped and therefore believe brevity is a virtue.

Either way, you’re looking at the wrong inputs in the equation. The better book is simply the one that provides you with more value. It is the better written book, regardless of length.

We tend to think that by adding more, we’re adding value. Adding a product to a bundle, adding words to a book, adding 3 bullet points to your argument – they all seem like logical value-adds. But that’s not necessarily true.

Table of contents

When More Is More

This discussion came up in our office when we noticed content marketing seemed to be taking a trend towards long form fluff. Instead of writing a good article, you’re rewarded for writing a long article.

People measure value for money in terms of qty. They pay more for more pages in books, more slides in presentations, more minutes in videos.

— Peep Laja (@peeplaja) February 2, 2016

If you’ve spent more than a minute on a marketing blog, you’ve probably seen this strategy. And for good reason – it works. At least for SEO, social shares, and authority building.

If It Works For SEO…

It’s not a secret that long form content tends to rank well. Apparently Google views longer content, generally, as providing more value to the reader.

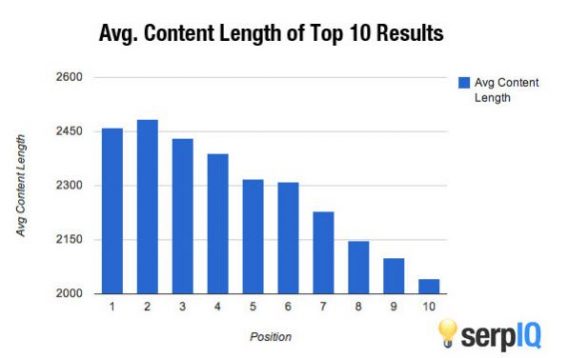

A much cited 2012 study by serpIQ showed the average content length of the top 10 results:

As you can see, the average content length for all of the top ten results was above 2000 words, and the top place got an average of 2416 words. Statements from Google themselves complement this correlative research to suggest that long content is valued by search engines.

Though, since the average post on WordPress is just 280 words long (according to WP CEO, Matt Mullenweg), most articles don’t follow these ‘best practices.’ Those who put in the effort for longer content tend to reap the rewards.

…and Social Shares

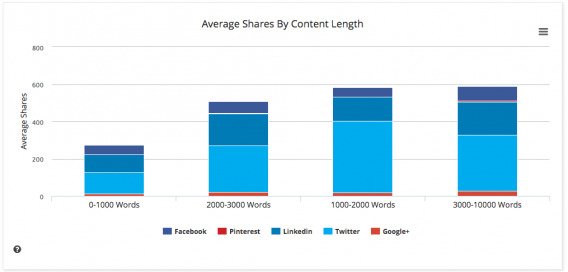

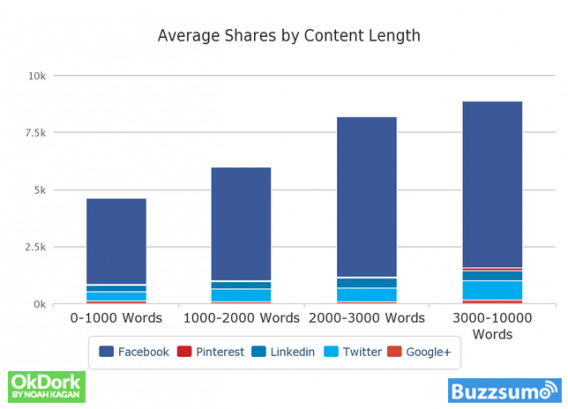

It seems that social media users value long content as well. At least that’s what BuzzSumo tells us about our own content:

Of course, 1000-2000 does better than 2000-3000, so it’s not purely linear. But anything over 1000 words is actually considered pretty long form in the wider world of inbound marketing. The data BuzzSumo provided on OkDork suggests similar trends:

Here they analyzed the top 10% of shared content, and it was clear enough that long form content was shared the most.

I could make up a narrative as to why that’s the case, but I won’t. Who knows? There’s a strong correlation here, but of course, there are examples of short form content doing surprisingly well. Again, it’s contextual and there isn’t a silver bullet answer.

My best guess would be that 1) long content gives more opportunities to place contextual keywords 2) long content delivers more linkable assets and 3) Google could perhaps view quantity of words as a proxy for search quality.

Long Form Fundraising Letters Convert Better

It works for fundraising letters, too, it seems. Jeff Brooks, Creative Director at TrueSense Marketing, wrote about his experience testing long vs short letters:

Jeff Brooks:

“I hate long letters. I wish they’d just get to the point. I bet you don’t care for long letters either. Nevertheless, long messages work.

I’ve tested long against short many times. In direct mail, the shorter message only does better about 10 percent of the time (a short message does tend to work better for emergency fundraising).

But most often, if you’re looking for a way to improve an appeal, add another page. Most likely it’ll boost response. Often it can generate a higher average gift too.

It’s true in e-mail too, though not as decisively so. In my experience, a longer e-mail outperforms a shorter one about two out of three times. Brevity may be a virtue in the e-mails you write to coworkers, but longer e-mails still get through to a lot of donors.

In surveys and focus groups, donors often complain about long fundraising messages. They say exactly what you or I would say: “I don’t have time to read something that long. Why don’t they get to the point?”

That’s what they say. But in real life, donors respond more often to long messages.”

David Ogilvy, advertising legend, supported this idea, saying, “all my experience says that for a great many products, long copy sells more than short… [A]dvertisements with long copy convey the impression that you have something important to say, whether people read the copy or not.”

In essence, he’s saying that because the copy is long, people assume it’s important. Long sales copy isn’t always the answer, though – you know things are contextual. But below I’ll show you why, when you’re writing long copy for the sake of length, it can actually weaken your overall argument.

Quantity as a Proxy for Quality

It’s generally assumed that more is better. We think that more options make us happier (they don’t), longer books contain more information (not always), and longer lists are more persuasive (not true – more on that in a bit).

In essence, we use length or amount as a proxy for the quality.

It’s similar to how we use price as a proxy for quality in certain product categories. It’s usually when quality is ambiguous and highly variable – the classic example is wine.

Researchers found that if a person is told they are tasting two different wines — one costs $5 and the other $45 (but they’re actually the same wine) — the part of the brain that experiences pleasure will become more active when the drinker thinks they are having the expensive wine.

A higher price actually equates to a more enjoyable experience – even though the wines are the exact same quality! We clearly do not always judge based solely on merit.

Is More Always Better? Enter: The Presenter’s Paradox

Now let me ask you a different question.

Imagine a scenario where I give one group of people a very expensive bottle of wine, and I give another group that same bottle of very expensive wine, but also give them a set of cheap plastic cups.

Which group will rate their gift as the more valuable one?

According to psychological research, it appears that the wine bottle alone elicits more value than the wine + the cups. Even though I’m technically and objectively adding value with the cups (small value though that may be), people will rate the combined package as less valuable.

Strange, right?

Bloomberg.com opened up a 2012 article by saying, “We are atavistic creatures, and even after we do all the arithmetic and reasoned thinking possible, our lizard brains are sometimes still making the judgment calls.”

Sound familiar? Other than the word ‘atavistic’ (which I love), the writer is saying the same thing marketers are constantly proclaiming: consumers aren’t always rational.

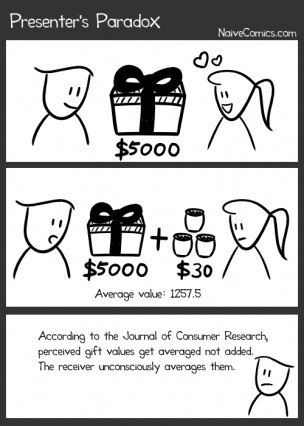

The wine scenario I presented above is an example of The Presenter’s Paradox, which means that when we, as consumers, evaluate value, we take the average of the components instead of the sum.

In the specific case of gift giving, researchers found that recipients appreciated an expensive gift more when it was given alone, as opposed to the same expensive gift coupled with a less expensive one.

Influence At Work explained the effect really well:

“Much like adding warm water to hot leads to a more moderate temperature, attempts to clinch a deal by adding extra features to an already strong proposal, could mean a reduction in the overall attractiveness of that proposal. In effect each additional feature or piece of information provided serves to cheapen the overall package.”

Clearly this phenomenon has wider implications than simply improving your dating life. It also has strong implications on sales, product, marketing, and optimization.

First, let’s think in terms of sales.

And similarly, at a job interview (selling yourself, essentially), it’s better to “list your MBA and your fluent French and then drop the mic,” as Bloomberg put it. “When you put absolutely everything that might catch a recruiter’s eye on your post-college résumé (glee club! bartending license!) you were making yourself look weaker, not stronger.”

That means you can probably take Microsoft Office off your LinkedIn profile.

A few other direct applications include:

- Copywriting

- Product bundling

- Content production

Landing Page Copywriting

Copywriting is basically sales on paper, so the same principles apply. It’s simple, really: more arguments, if they’re subpar, weigh down the few good arguments. It’s much better to find your strongest arguments and focus on those.

Here’s an example. Which of the two arguments do you think is most persuasive?

Well, the researchers found that the shorter argument was more persuasive. Four public service announcements were studied, actually, and researchers found that the arguments were most persuasive when containing a few highly strong reasons and no mild ones – in all cases.

When you’re writing a long form sales page, though, you don’t want to leave out too much information. You want to include anything relevant to your target audience, or you might miss out on prospects.

At the same time, you can’t overcrowd your presentation and hope everything’s considered a positive – that’s known as “feature bloat” to software writers. You need to have some sort of prioritization so your presentation isn’t a jumbled mess of junk.

Bloomberg offers four great tips to toe the line:

- Keep the standard up: adopt an attitude that emphasizes quality. Sweat the details. E.g. “If you run, say, a publishing enterprise such as a blog, the captions have to be as sharply written as the stories.”

- Edit ruthlessly: when writing, speaking, selling, or presenting, be terse. “Brevity, always a virtue, is doubly so when you’re trying to avoid watering down your impact.”

- Have a sense of proportion: if you can’t avoid the weak stuff, make the good stuff heavily outweigh it.

- The Ginsu approach: sequential-selling. Basically, “But wait! There’s more!”

The last one in particular is interesting, because it’s sort of a sales trope (think of any infomercial you’ve seen). Influence at Work clarifies this, explaining that The Presenter’s Paradox can be saved by using the Ginsu approach. In addition, they recommend trying to add lots of extra value to a few selected customers, instead of a small extra for every customer:

“Doing so affords you two potential benefits:

First you could avoid losing money providing extra benefits to customers that, like the case of adding warm water to hot, will actually reduce the temperature of your overall offer.

Second you bring to bear the powerful force of reciprocity, by providing customised and significant additional benefits targeted to your most cherished customers.”

I’d like to add one more item to that list (at the risk of lowering its overall value): truly understand your target audience and your strongest arguments.

How do you do this?

Many ways, of course. Our agency uses the ResearchXL model to explore what problems exist on websites and the potential solutions to those. You can find out what resonates with your audience via User Testing, customer surveys, on-site surveys, 5 Second Tests – essentially, qualitative research.

Voice of Customer research, in particular, is an incredibly effective method of finding the arguments that resonate with your audience – because the copy comes directly from your customers. Use a tool like Usabilla, Kampyle or iPerceptions for this.

Know also that there are different types of people, and they prefer different types of copy. A study at Brown categorized readers in two ways:

- Explanation fiends (want more information)

- Explanation foes (less willing to buy after learning)

And it depends on the product, too. A good rule of thumb is that the more expensive/complex the offer, the more copy/arguments are needed.

Barry Densa gave a really good example with soup:

Barry Densa:

“Most people shopping for soup are only interested in the price of their favorite brand, be it Campbell’s or another, and whether or not there’s a coupon attached—neither of which requires a lot of supportive copy.

But, if Campbell’s brings to market an all natural, gluten and fat-free tomato soup that helps you lose weight, sleep better and score a raise from your boss on Monday morning… they’ve got a lot of persuading to do.

As does an investment newsletter selling 12-month subscriptions at $2,000-a-pop.

A 2-inch-by-2-inch print ad, a one-paragraph email, or a tear-off coupon will not have enough selling power, information, and enticements, to lift $2,000 out of anyone’s wallet.”

Even with long copy, though, you still need to feature only your most persuasive arguments. The best way to find these is through a combination of qualitative research/voice of customer research and A/B testing to find empirical insights.

Product, Pricing, and Packaging

Product bundling is such an established marketing technique, that it seems strange to advise against it. But if you paid attention to the above research, you know that this is a blatant example of The Presenter’s Paradox.

When you try to bundle an expensive product with an inexpensive one, it can actually lower the perceived value.

According to a study cited by HBR, people were more likely to purchase a $2,299 home gym when it was offered alone than when it was combined with a fitness DVD.

Most surprisingly, they found that, while people were willing to pay $225 on one piece of luggage and $54 for another when purchased separately, they’d only pay $165 for the items as a bundle ($60 less than the expensive one alone).

Product bundling, then, is not a silver bullet. There are ways to do it right, though. Roger Dooley has spot-on advice on doing bundling correctly:

Roger Dooley:

“If you are thinking about bundling multiple products, do it right:

- Avoid mixing a cheap item and an expensive item and simply promoting the package.

- If you are mixing products with different values, establish the value of the individual items first, particularly the most expensive one.

- Take a lesson from infomercial producers and emphasize the additive nature of bonus items.

- Focus on non-price attributes of the product (e.g., durability or comfort) – the researchers say this will reduce the devaluation effect from mixed-value items.”

Content Marketing: Quality Vs Quantity

When it comes to content marketing, or any type of campaign, quality trumps quantity.

We’ve noticed this on the CXL blog: your reputation is only as good as your last blog post. Putting aside any arguments for SEO or other factors, consistent quality is the most important variable in establishing a good brand reputation. As Pamela Vaughan from HubSpot put it:

Pamela Vaughan:

“Presenter’s Paradox, make for a compelling case for quality over quantity in content creation, doesn’t it? The lesson is simple: Don’t dilute your high-quality content with mediocre or low-quality content. The consequence for doing so is the cheapening of your audience’s overall perception of your content and thus, your brand. And who wants that?”

Though, I believe that with a good process and talented people you don’t have to sacrifice quantity because of quality (good journalists learn to work both fast and well).

Conclusion

More is not always better.

In fact, if you couple highly valuable things with less valuable things, your customer tends to average them – not add them together like you wish they would.

So when you’re writing a sales letter, only pick the best arguments. Don’t package pricey/valuable products with lower value products. Don’t put worthless items on your resume (or mention them at a job interview) just to fill up space or time. Don’t give your girlfriend two t-shirts and a box of chocolates with her engagement ring.

Essentially, think about your offers in terms of averaging, not addition. Three amazing bullet points on a landing page will almost definitely be more persuasive than a longer list that includes suboptimal arguments.

Outstanding & insightful. Glad I opted to get browser alerts for new CXL posts. :)

Thanks! Glad you liked the article

I wonder if this works the other way around, to make an expensive item seem cheaper than it really is?

Does it only lower the perceived value, or could it be used to lower the perceived price?

Hey Alan,

Good questions.

With perceived value experiments, I think it’s a bit of an art. There are certainly studies that show us how to use human “irrationality” to increase perceived value (we wrote an article all about that if you’re interested: cxl.com/perceived-value/), but I’ve been thinking a lot about a Nassim Taleb quote I read recently…

“The psychological experiments on individuals showing “biases” do not allow us to understand aggregates or collective behavior, nor do they enlighten us on the behavior of groups.”

So to answer your question, “could it be used to lower the perceived price?” I guess the answer is “maybe.” It’s certainly something you could test :)

And for further inspiration, here’s an article Peep wrote on a bunch of pricing experiments worth trying: cxl.com/pricing-experiments-you-might-not-know-but-can-learn-from/

Hope that helps!

Alex

Thanks Alex for the detailed article and explanation. About the experiment with the wine bottles -its interesting that it works only while you show it to someone without him knowing about the other option. If you show both options, with your example – the one with the plastic cups along with the one without, rationality comes in and people would choose the option with plastic cups.