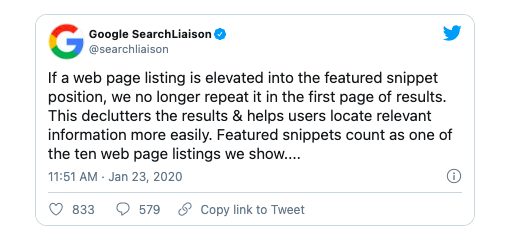

On January 23, Google announced that, “If a web page listing is elevated into the featured snippet position, we no longer repeat it in the first page of results.”

Historically, a “standard” link—in addition to the linked snippet—also appeared on Page 1. That meant that owning a featured snippet meant owning two Page 1 results.

How has the recent change affected traffic? How much was “double dipping” actually worth? It’s a hard question to answer. Few sites have enough featured snippets to offer anything other than (very) anecdotal evidence. Those that do, typically, are unwilling to share traffic data.

Wikipedia is an exception. It owns more than 1 million featured snippets, and raw pageview data is publicly available.

While this change is only a week old—and almost any quantity of data qualifies as anecdotal on the scale of the World Wide Web—we took an early look at the impact of the change.

Methodology

- In Ahrefs, we went to the Site Explorer for en.wikipedia.org.

- In the Organic keywords report, we filtered keywords to include only (1) SERPs with a featured snippet that (2) Wikipedia owned.

- We exported the 10,000 highest-volume keywords.

- We used Wikimedia’s REST API to pull pageview data for January 20–21 (the Monday and Tuesday before the Wednesday change) and January 27–28 (the Monday and Tuesday after the change).

- We averaged pageview totals for each two-day period and compared traffic before and after the change.

Limitations

Here’s why this research—and every other SEO study—should be taken with a grain of salt:

- We’re a week in—let’s pump the brakes on drawing hard conclusions.

- The list of keywords for which Wikipedia owns the featured snippets was exported on January 28; Wikipedia owned most of those snippets on January 20–21 but certainly not all of them. (Featured snippets are volatile.)

- Pageview data from Wikipedia isn’t segmented by source or device, nor are unique pageviews differentiated from repeat views. We assume that most pageviews are unique and that organic search accounts for the bulk of total pageviews (i.e. pageview data is directional for organic traffic).

- Some Wikipedia articles experience traffic spikes based on news, events, and seasonality.

- This is a 10,000-keyword study of 1 site. Even a million keywords for a thousand sites would qualify as “anecdotal evidence” on the scale of the Internet.

- Technical quirks while culling this data reduced the pool of keywords from 10,000 to 9,819.

Results

The average Wikipedia page that owned a featured snippet lost 6.89% of pageviews. The median page declined in pageviews by 1.69%.

Overall, 55.4% of Wikipedia articles with featured snippets declined in total pageviews during the assessed period.

Using the interquartile range and “fences,” we can identify outliers. Controlling for outliers makes sense. The most dramatic pageview changes resulted from:

- Snippets won or lost;

- Trending topics that spiked pageviews between the data pulls (e.g., “grammy winners”).

Based on those calculations, outliers were articles that lost more than 34.5% of pageviews or gained more than 22.9% of pageviews.

When controlling for outliers, the average article lost 2.17% of total pageviews; the median article saw a decline in pageviews of 1.81%.

Half of all articles (with outliers removed) experienced a change in pageviews between -8.94% and 5.26%—a meaningful change but hardly cause for alarm given the variability in high-volume SERPs with featured snippets.

When excluding outliers, the total percentage of articles that declined in pageviews rose slightly, to 56.6%.

How should these results affect your strategy?

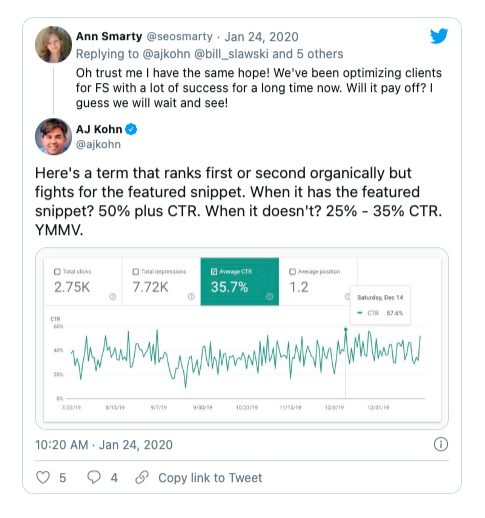

Featured snippets represent the coveted “Position 0.” Most SERP-watchers report an increase in traffic when a site owns a featured snippet:

(Whether the all-out strategy to earn featured snippets represents a Google-enforced Prisoner’s Dilemma, as Rand Fishkin argues, is another topic.)

Here are three things to keep in mind:

1. This data should help you set expectations.

No two sites (or keywords or snippets) are the same, but the sky isn’t falling—or, if it is, only in bits and pieces. Most of the value of owning a featured snippet remains.

Half of all Wikipedia articles experienced a pageview loss greater than 1.81%, but only 25% of articles endured a loss greater than 8.94%. That means, of course, that 75% of articles saw a smaller loss, if any.

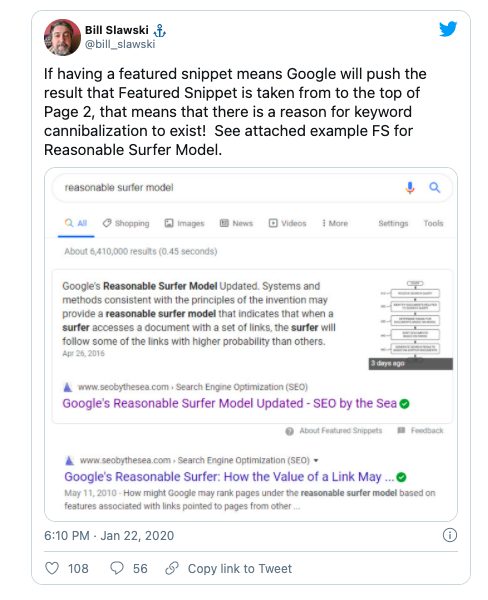

2. Your keyword cannibalization “problem” may not be a problem.

Whether you call it “keyword” or “search intent” cannibalization (or deny its existence), the reality is that, for a given topic, Google usually wants to surface the most relevant page on your site—not the two- or three- or five-most relevant.

Targeting the same keyword or intent on multiple pages often means that one of the pages languishes beyond Page 1, or, in some cases, that the two pages divide signals, relegating both to organic obscurity.

But the end of double-dipping opens the door for pages of secondary relevance to make their way back to Page 1. As Bill Slawski notes, what constituted an “SEO issue” a week ago may now be a way to preserve the double-dipped experience:

It’s unlikely that there’s enough value in that second URL to support an active effort to increase cannibalization, but you may want to check whether this change has made valuable a page you previously considered redirecting to or consolidating with a higher-ranking one.

3. If you didn’t have the snippet but were in Position 2, that URL may now be above the fold.

In theory, URLs in Position 2 may now earn more clicks. That depends, of course, on whether the snippet was drawn from the URL in Position 1 and what the rest of the SERP looks like.

One reason that changes to Wikipedia’s pageviews may not have been that dramatic is that the Position 2 URL—in addition to being buried on mobile results—is barely visible (if at all) on desktop.

The gap between the number of users who don’t scroll at all and those who scroll some is likely greater than the gap between those who scroll some but never reach a URL beyond Position 2 (i.e. most people who scroll at all likely see multiple other results).

For “glutamic acid,” a query for which Wikipedia pageviews declined by 3.66%, the second URL is barely visible.

Not surprisingly, it’s nowhere to be found on mobile:

For another query, “david vs goliath,” Wikipedia lost 3.73% of all pageviews. The URL in position 2 is still well below the fold (a People Also Ask box is below the videos, too):

The greatest gains for URLs below the featured snippet are likely for queries in which no other SERP features appear directly below, as in this query for “operation overlord” (pageviews to Wikipedia declined by 1.49%):

Finding the non-snippet result on mobile still requires a bit of scrolling:

Conclusion

In SEO, the more important question is often “How will this change affect my traffic?”, not “How can I undo this change?” We have limited control.

Organic search, and Google in particular, is many sites’ most powerful acquisition channel—present site included. The end of “double dipping” hasn’t added a laundry list of tasks to my SEO to-do list.

But knowing how this change may affect our site can help us—or you or your clients—project traffic changes and, if necessary, adjust investments in other channels to balance out the effect.

Further, this small study illustrates the value of using Wikipedia to gauge the impact of SERP changes. Third-party tools like Ahrefs deliver ranking and SERP data that, when paired with Wikipedia pageview data, can—if you can stomach directional data—illuminate trends more quickly.

Nice article, it was good to read!

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it!

I think this is a good move as now it will be a fair chance. Otherwise, a single article is occupying both 0 & 1 position which looks unfair. Let’s see how many more changes are on the way.

Thank you for the post, I appreciate you going through all this data.

Here’s my question: Wikipedia’s featured snippets are historically “side snippets”, for which Google still shows a listing. You can test this on both mobile and desktop for the term “cleopatra”.

Wikipedia has the snippet and the #1 listing, making this update much less problematic for their traffic. Do you think that is why you saw an insignificant loss?

Not all (or even most?) of their snippets are “side snippets,” which, in Google officialdom, are called “knowledge panels.” Those tend to show up when the query is interpreted as asking for information about an “entity,”

(e.g., a person, a movie, a brand, etc.). But Wikipedia also has tons of snippets for random informational queries, like “is pluto a planet.”

I didn’t identify which of the queries in my sample returned knowledge panels vs. “regular” featured snippets; it’s another potential confounder.