This is my last week at CXL. It’s bittersweet. I started on a Monday and published my first post on a Thursday. Since then, it’s been rinse and repeat for nearly two-and-a-half years.

In sum, I wrote 46 posts and edited another 156. That works out to about a half-million words and a new post every 4 days for 870 days.

Through it all, here’s what I figured out—and what I failed to solve.

Table of contents

- 5 things I learned

- 1. Your brand isn’t what you just published; it’s what people see most often.

- 2. Set a hard deadline that’s barely feasible—then use that pressure to improve processes.

- 3. Don’t try to create a perfect strategy; execute a good strategy more often.

- 4. If you want a unique voice, write about topics you’ve got no shot to rank for.

- 5. Use quantitative data for links, qualitative data for shares.

- 3 problems I didn’t solve

- Conclusion

5 things I learned

1. Your brand isn’t what you just published; it’s what people see most often.

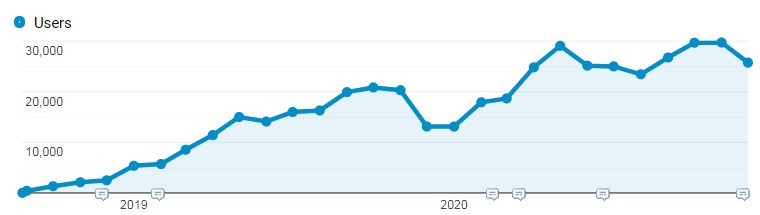

If, like CXL, you have 750+ posts floating around the Internet, your content brand isn’t what your strategy is now—the one that’s affected, say, your last 20 or 30 posts. It’s the other 700 posts that account for 95% of your traffic (since new stuff takes time to rank).

If your top five blog posts—which were published years ago—account for 30% of new users, then those posts are your brand for one in every three people. When someone finds a broken link, missing image, or dated bit of advice, your reaction may be, “Oh, that post? We did that years ago.” But for them, it’s all they know.

The division of traffic, not recency, shapes your content brand. That’s all too easy to forget. We work in the moment. We form forward-looking strategies.

Ask: If none of our content had a publish date, if there were no time-ordered list of posts, which articles would we say are the core of our brand? The most important topics and high-traffic posts may be buried deep in your blog roll. They should be top of mind.

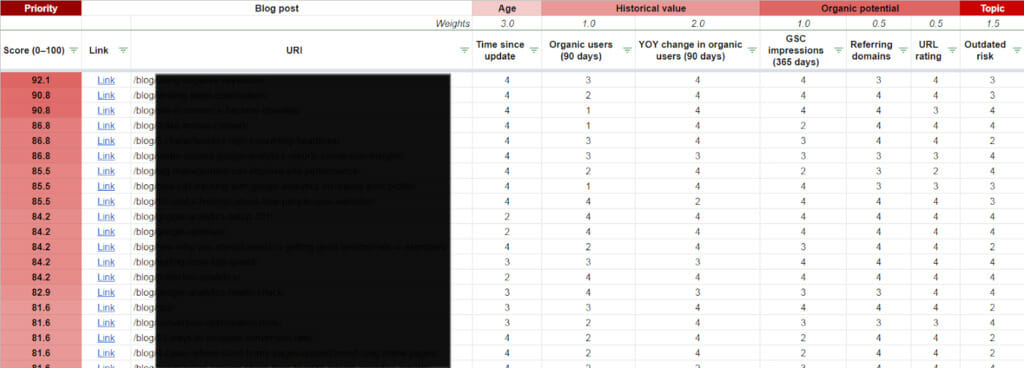

We now update twice as many posts as we publish. It doesn’t take as long (one to four hours is enough to satisfy users and search engines), but it’s the most valuable thing we’ve done for organic traffic and the biggest opportunity for our content brand.

We started by fixing the big mistakes (broken stuff), and will, in second and third iterations, work on smaller things—off-brand tone, so-so articles, etc.

2. Set a hard deadline that’s barely feasible—then use that pressure to improve processes.

An old boss used to say, “Deadlines are your friend.” For her, deadlines staved off procrastination. But they’re also a cap on quality.

Everyone publishes on a budget. Time is part of that budget. Journalists have to make the morning paper. Magazines have to get out each week. Even academics—the most immune to deadlines—have to wrap up articles and books in time to earn tenure.

It’s a balance. If you told me I had to publish a post every day, the quality would go down. But if you didn’t demand any cadence, there’s no way I’d say, “Twice a week sounds good.” That’s at the fringe of feasibility.

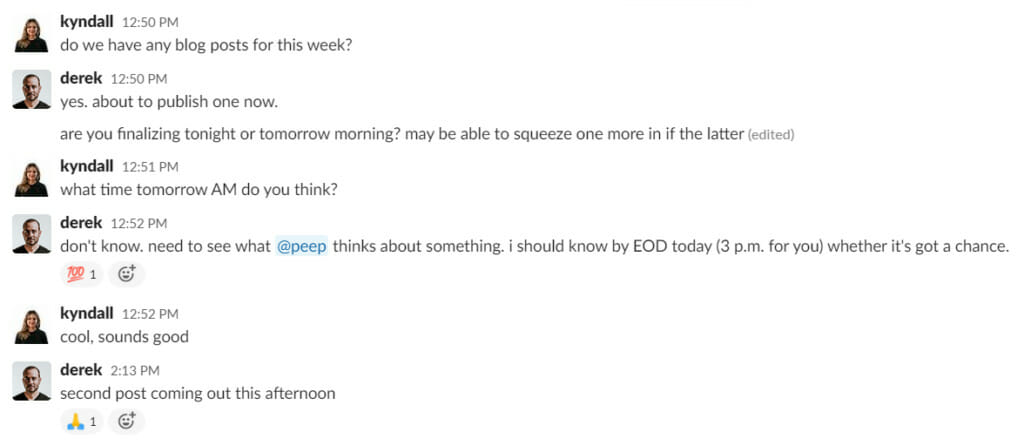

I can’t tell you how often I scrambled to get a post out the door in time for the Thursday morning newsletter. (I failed every six weeks or so.)

But that pressure has been a great catalyst for process development. It’s absolutely possible to get a high-quality post out the door in 15 hours. A fixed deadline inspires efficiency. (It also banishes the low-ROI fiddling that can drag out final revisions for an extra week.)

Over the course of a year or so, running the blog went from a 40-hour-a-week gig to a 25-hour-a-week effort. The surplus time then went to stand-alone projects, post updates, etc.

(Yes, I could’ve used it to build more cushion into the publishing schedule, but that would’ve only lowered stress—which was manageable—not add business value.)

If CXL didn’t have a 10-year precedent of what a “good” post was or how often we usually published, it would’ve been difficult, from Day 1, to know that we had the right balance of publishing more versus publishing better.

But if you need a starting point, know that posts like ours take about one hour per 100 words.

3. Don’t try to create a perfect strategy; execute a good strategy more often.

I came to CXL after several years at an agency. Agency life teaches you the value of pretty slide decks. You need them to win client buy-in. If you have to rework (or abandon) a strategy, clients lose faith.

As a result, you spend a lot of time trying to create an airtight strategy—one that you’re confident will work, with milestones spread across several months. But you’re relying on a lot on hypotheticals and “best practices.”

No strategy guarantees success, especially at a micro level (e.g., picking topics for blog posts). We’ve published some great things that few people saw. We’ve published some mediocre posts that drive tons of traffic and leads. (Google’s standards are lower than ours.)

One post went viral because—unbeknownst to us—it gave exquisitely timed reassurance to an anxious influencer, who then shared it.

You can’t plan for this stuff. What you can plan for is the general shape of things—a makes-sense-but-not-foolproof strategy. From there, you’ll have more success if you execute that strategy more often. (Executing on it more often also gives you real-world feedback—the best way to refine your strategy.)

4. If you want a unique voice, write about topics you’ve got no shot to rank for.

Yes, this is counterintuitive, but hear me out.

If you’re just starting in content marketing, these are the typical steps for a by-the-book, keyword-targeted strategy:

- Identify the most relevant topics you should write about.

- Realize that the SERPs for the “core” aspects of that topic are way too competitive (i.e. dominated by big sites with tons of links).

- Find related, long-tail topics that have less search volume and lower competition.

- Publish on those until your domain is strong enough to go after the original keywords.

It makes sense. It drives traffic. But it will destroy any chance to stand out. The strategy, in effect, asks, “What keyword volume will remove all incentives to publish something unique?”

As a distribution channel, search rarely rewards tone, design, or angle. So much content looks the same because everyone’s style guidelines try to please the same search engine.

Flip the script:

- Identify the most relevant topics you should write about.

- Pick topics that big sites own, ones for which you have no prayer to rank for.

- Create content on those topics with a novel take or presentation.

- Embed those unique elements—of language, visuals, whatever—in all the content you create.

If you work to get eyeballs on your content before search is involved, you’ll establish the standards you need to get attention, now and later. (Retrofitting existing content is clumsy and expensive.)

5. Use quantitative data for links, qualitative data for shares.

Put another way: Quantitative data is the proof, but qualitative data is the story. This isn’t a shock to those who do conversion research—quant data is the “what”; qualitative data is the “why.”

But if you want a compelling research study, you’d better ask at least one open-ended question. Code those qualitative responses (ideal H2s) and use individual excerpts to add raw energy to your write-up. That’s what pulls people through an otherwise dry report and gets social shares.

The quantitative data, by contrast, wins the links—it’s the benchmark data that people love to cite.

A final note: Don’t overcomplicate original research. The U.S. News & World Report studies on cities, colleges, hospitals, and schools rely on about a dozen data points. All but a few are publicly available. The rest fall into one of three categories:

- A purchased dataset (e.g., from Gallup);

- One of their other studies (e.g., using hospital and school data for place rankings);

- Some non-scientific email survey.

The third category is key. It generates “proprietary” results—the one extra data point you need to keep anyone else from replicating your study.

Grab some quantitative stuff that’s already out there. (Kaggle has a ton; Siege Media cataloged many sources.) Run a survey with an open-ended question. Mash mash. Publish.

If only everything were so simple.

3 problems I didn’t solve

Too many of these sorts of posts are triumphant—challenges faced, challenges met. I’m walking away knowing that there are things I didn’t get right or haven’t solved.

It’s engaging to work on hard problems; it’s disappointing not to see them through to a cathartic resolution.

1. Blogs are hamster wheels. I should’ve stepped off more often.

This is the single biggest reason I didn’t solve more problems. The weekly fist-pump moment of this job is right after you publish the second post of the week, usually Wednesday afternoon or Thursday morning.

The rest of the week is a denouement—a much-needed winding down to get ready for next week’s plot twists and frenetic climax. The blog is always the main event, and it requires heads-down work, not introspection.

That slows progress. As Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman’s long-time research partner, said, “The secret to doing good research is always to be a little underemployed. You waste years by not being able to waste hours.”

I could’ve made blog production more efficient—or published better stuff—had I taken the occasional Monday and said, “Okay, this week, the most important thing is improving how we operate, even if it means we don’t publish anything.”

I never did.

The result was incremental improvement. The 15-hour reduction (from 40 hours to 25) that took over a year was probably achievable in six months had I stepped out of the wheel once a quarter.

For anyone running a blog or thinking of starting one (godspeed), build thinking time into your editorial calendar—at least one week per quarter. No one outside your company will care if you don’t publish for a week, and you’ll get better a hell of a lot more quickly.

2. Those “side projects” are usually unfinished—or not very good.

Like any startup, we have tons of ideas. Also like any startup, we don’t have the capacity to execute them. We do, of course, have the boundless enthusiasm to think we can execute them.

That spare 15 hours after the last post goes out isn’t the best time for creative problem solving. It’s a great time to update blog posts, do email outreach, or other fuzzy-brain tasks, but you—or I, anyway—need the first fruits of my brain to execute complex content projects.

With rare exception, the additional content projects I worked on fell into one of two buckets:

1. They didn’t get done. We have several dusty strategy docs and a few half-baked projects.

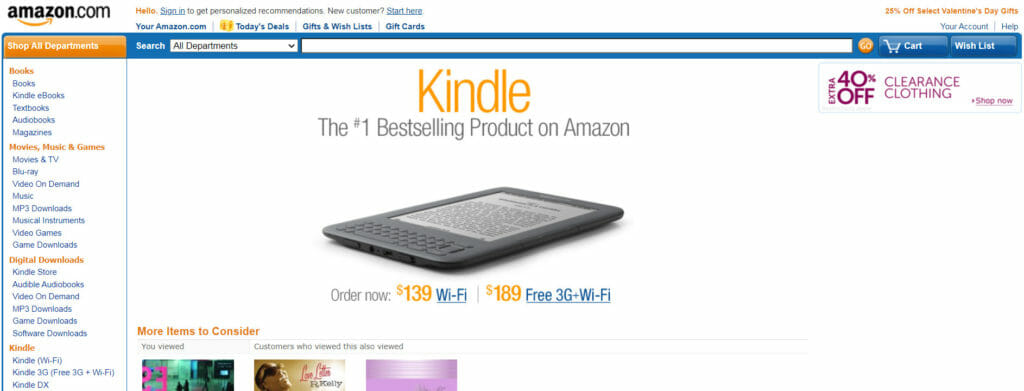

For example, we grabbed thousands of screenshots of Amazon’s homepage over the last 20 years. We planned to analyze them to create a visual history of one of the web’s most ardent champions of iterative design.

Summer 2019 was the last time I touched it. We adjusted priorities. We had a domain migration that December. And, oh yeah, we started developing a new product (Adeft).

2. They weren’t very good. Here’s another example: We wanted to increase traffic by targeting head terms that were too broad for a blog post (e.g., “email marketing”).

Hub pages were a cheap option because we could add a small amount of original content (e.g., definitions, FAQs), then automatically pull in relevant posts, webinars, and courses based on WordPress tags.

But we had only bare-bones design and dev resources. “We’ll put out a beta version and see if it gets traction,” we said. But these pages needed to earn links to rank. They needed to be so good that we were proud to promote them. They weren’t.

So, each one drifted around Page 3 or 4 of search results, as invisible as a slim volume in a cavernous library.

In retrospect, it would’ve made sense to outsource some of these projects—give them to people for whom they could’ve been the number-one priority.

That, or we should’ve shoved the blog out of the way for a week here or there. But it’s a hard sell (to yourself or others) to sacrifice output of a thing that you know works.

About 60–70% of a given week can go toward serious, creative work. The rest isn’t wasted (plenty of fuzzy-brain work is super valuable), but I have too often assumed that all hours are equal.

3. Some experiments take a long time to run (maybe too long for a startup).

The biggest “before-and-after CXL” change in my thinking has been to go from a strategy- to experimentation-centric workflow.

I have Peep and, as a discipline, conversion optimization to thank for that. I move faster. I spend less time pondering. (Why speculate when you can get user feedback?) New ideas justify a test, not a strategy.

But the A/B testing mindset often defaults to two- or four-week cycles. Those are comically short time periods if you work in content or SEO.

So how, at an experimentation-focused startup, do you iterate rapidly if you need six months to get back data? Should you stick to a strategy if a shift in your product or market resets priorities?

I don’t know.

Conclusion

For the life of me, I can’t find who tweeted(?) it, but someone on some platform once wrote that when things, as they do, get all startup-y, it’s best to “roll down the windows, turn up the music, and keep driving.”

That’s good advice. And this has been great fun.

Best article I read this year

Many thanks!

hear, hear. My comment was too short before but it should be fine now.

Thank you!

Hi Derek,

This is a wonderful post! I just wanted to skim through the page when I clicked but I ended up reading every word. Great writing.

I love your point about stepping off more often. But it’s what most people in a high-pressure environment want to do but rarely find time to do.

Again, it can be difficult when you set hard deadline that’s barely feasible (your number 2 point). Overall, many things I learnt here.

I wish you good luck in your future endeavors.

Thank you, Samuel. I’m glad you enjoyed it. As with all worthwhile things, they are hard to do.

Cheers.

Thanks Derek. I enjoyed this post. And thanks to Peep for sending it.

Not all time are equal. I got that.

We live in a Power Law world – Peter Theil.

Thanks, Jeremiah.

Nice,,, Agreed with Editorial calendar does hep a lot,, first of all it takes out the burden of thinking what to write, as you know the first hour of the day what you going to do today.

Also agree with that the spare time cant be used for creative things..

But the side project could work,, I think the side project has to be turned into primary project for a short period of time, and then they work.