“How can a person be induced to do something he would rather not do?”

Researchers Jonathan L. Freedman and Scott C. Fraser asked that question more than half a century ago. In their era, it usually meant convincing someone to endure a pitch from a door-to-door salesman.

In ours, it often means incentivizing web form fills—gently prodding others to part with personal information that, they fear, could spark a swift, relentless inbox invasion.

Yet digital marketers have only recently recognized that applying this decades-old research to online forms can generate more leads and sales—and upend the conversion optimization best practice of “shorter forms equal more conversions.”

Table of contents

What is the foot-in-the-door technique?

The foot-in-the-door technique is a persuasion tactic that starts with a modest request, then follows up later with a larger request, in order to increase the chances of succeeding with the larger request.

It’s the opposite of high-pressure sales that go straight for a signature on the dotted line.

The foot-in-the-door (FITD) technique is not new. Even when proposed as a psychological concept in 1966 by Freedman and Fraser, the phrase “foot in the door” had been commonplace for decades.

Decades of research have upheld the effectiveness of the FITD technique.

In one of the studies from the authors’ original paper, they found that asking residents to put up a small “Drive Carefully” sign in their yard—the foot in the door—and returning later to ask them to put up a larger sign was vastly more successful (76% compliance) compared to asking residents to display a larger sign from the start (<20%).

A digital foot-in-the-door

Researchers later confirmed that a digital foot works as well as flesh and bone. In one study, they emailed half the participants for help with a file conversion issue, then followed up with an unrelated request to fill out a survey. The other half were sent the survey request directly.

Some 76% of the initial respondents completed the 40-question survey; only 44% of the others did. Their conclusion: “This ‘electronic foot-in-the door’ turns out as effective as in a situation where the interaction is synchronous (face-to-face or by phone).”

Why the foot-in-the-door technique works

A key to understanding the FITD technique, Freedman and Fraser note, is that the two requests need not be related:

The basic idea is that the change in attitude need not be toward any particular issue or person or activity, but may be toward activity or compliance in general.

Why? Because the FITD technique, many psychologists believe, relies on self-perception theory. Freedom and Fraser describe the human mindset:

Once [someone] has agreed to a request, his attitude may change. He may become, in his own eyes, the kind of person who does this sort of thing, who agrees to requests made by strangers, who takes action on things he believes in, who cooperates with good causes.

The initial request, research reinforces, establishes a disposition of “helpfulness” that leads to increased compliance.

For example, agreeing to tie a shoelace for someone with back pain in a supermarket parking lot makes you more likely to agree to briefly monitor another stranger’s shopping cart when you approach the entrance moments later.

Self-perception theory, however, isn’t the only reason that FITD may work. Critically, the reason that the FITD approach may work greatly influences how you should apply it to web forms.

Shorter forms increase conversions, right?

Peep Laja explained that the best thing you can do to improve conversions is to get rid of as many fields as possible.

Oli Gardner explained if you want to increase form conversions, you must consider reducing the number of fields.

Plenty of studies like this one or this one—and, I’m betting, your own experience—back it up. After all, shortening forms is a best practice because it usually works.

But no best practice should be deployed without testing. (No one mentioned above advocates test-free implementation, and don’t expect this post to bail you out either.)

Unlocking the potential of longer forms hinges on recognizing that the number of form fields may not be the main source of form friction.

Shorter forms can also fail

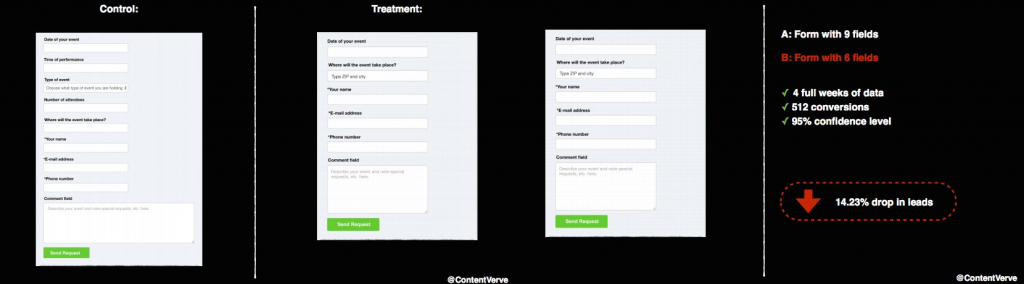

As we wrote a few years ago, changing your form design to include fewer form fields can backfire. That’s exactly what Unbounce’s Michael Aagaard experienced with a site that connected people with entertainers for events.

He told his story at CTAConf:

We’re asking for a lot of information. We’re asking for date, time, type of event, number of attendees, location, name, email address, phone number, a comment field where you have to describe the event. A lot of information! And all I really want to do is just contact an entertainer.

So, to me, the solution was obvious here. Based on experience, it’s way too much information. So, let’s shorten it down and ask for less information. I finally convinced the client to let me remove three form fields. I wanted to remove more, but I could only get away with removing three. But that’s still one-third of the form fields—a lot less friction.

The result? 14% drop in conversion.

I removed all the fields that people actually want to interact with and only left the crappy ones they don’t want to interact with. Kinda stupid.

Distilling a form down to its most intimidating fields is one reason to retain longer forms. There are other well-known justifications, too, albeit anecdotal ones:

- Longer forms may reduce lead quantity but increase lead quality. Increased form friction weeds out less-interested visitors.

- Longer forms may work equally well if the reward justifies the effort. A strong lead magnet motivates form fillers.

But none considers the potential psychological impact of longer forms, especially multi-step forms that engage visitors with a simple ask before requesting a friction-inducing piece of information.

That strategy is called the foot-in-the-door technique.

3 theories that explain why FITD works (with examples)

While academic research leans toward self-perception theory as the primary explanation of the foot-in-the-door effect, it’s not the only theory. Two others—Cialdini’s “commitment and consistency” principle and the “mere-agreement effect”—also surface in academic studies.

In other words, the FITD effect may occur for different reasons in different situations. Each reason has significant implications for whether the FITD technique will work on your site—and how to set up forms for maximum effect.

1. Self-perception theory

- When it works best: Surveys, review requests

- Why: People want to perceive themselves as helpful

As part of their initial study, Freedman and Fraser ran a test with 156 housewives in Palo Alto. The “big request” was to allow a team two hours of access to their home to see which household products they used.

Prior to making that large request, they divided their subjects into four groups and called each to:

- Survey them over the phone about their usage of cleaning products.

- Merely ascertain whether they would be willing to participate in a phone survey.

- Provide information about the research firm and its intents.

- Ask directly for permission to conduct the in-home survey.

Women in the first group agreed to the “big ask” of an in-home survey 52.8% of the time, more than any other group (whose accepted requests totaled 33.3%, 27.8%, and 22.2%, respectively).

“I need your help,” is the underlying trigger for self-perception theory. And, stated or unstated, it’s equally potent when it comes to on-site surveys.

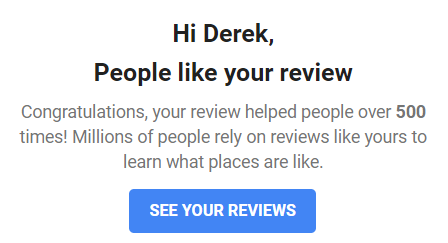

Google Maps does a great job with this. Rather than haranguing me to leave another review with generic “We value your opinion” statements (which boost my self-importance but do nothing to trigger a FITD effect), they highlight how helpful I’ve been in the past, then offer to show me further evidence of my altruism:

Encouraging me to see my reviews (a small request that reinforces my self-perception as “the kind of person who does this sort of thing”) is the perfect first ask to get me one giant click closer to leaving more reviews.

For your surveys, you may ultimately want an email address or phone number to follow up with respondents. And, for reviews on Facebook or Google, you’re asking someone to declare publicly their feelings about your business. Those are big requests.

If you require either (the digital equivalents of an in-home visit), start by gathering anonymous responses and reinforcing the helpfulness of user reviews to others.

2. Commitment and consistency principle

- When it works best: Lead generation, user requests for rates/estimates

- Why: People are compelled to finish what they start

One of Cialdini’s six principles of persuasion, “commitment and consistency” argues that once we start something, we want to finish it. Thus, a small request starts us down a path that a later, larger request completes.

(Cialdini’s principle relates to several others, such as the Ovsiankina effect—the tendency to restart an interrupted action—and the Zeigarnik effect—our higher recall for incomplete or interrupted tasks.)

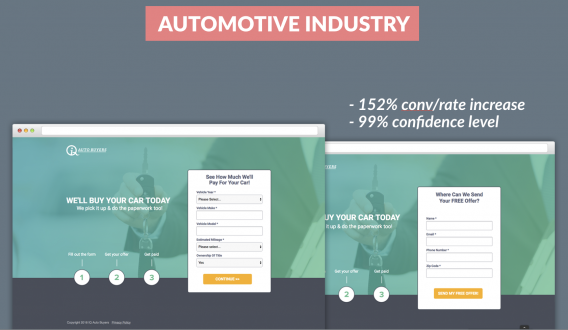

It’s the primary reason that KlientBoost’s Johnathan Dane, who wrote about using a similar approach last year, has succeeded with FITD for his clients. Like Aagaard, Dane realized that perennial shortening of form fields reduced many to a single type of request—one that unmasked anonymous users.

KlientBoost began implementing a process that has become an almost universally successful test for clients: breaking up single-page forms into multi-step forms. Multiple steps create a sense of process that draws visitors through to completion.

The “foot in the door,” for KlientBoost analysts, is an initial question (or three or five) that asks for non-identifiable information. At the completion of the process, visitors submit contact information to receive results (e.g. home loan rates).

The initial requests are essential disclosures for users to get the answer they want, and until the end of the process, users are uncertain that they’ll even need to enter personally identifiable information. Only then—after having taken all but the last step—are they prompted for contact information.

For several clients, it has worked wonders. KlientBoost shared a few examples of foot-in-the-door success:

3. Mere-agreement effect

- When it works best: Community building, strong value alignment

- Why: Perceived similarity breeds cooperation

You and I are two peas in a pod. That’s the impact, according to researchers, of the mere-agreement effect.

An initial point of positive response creates rapport between two parties that can lead to ongoing, escalating agreement—all the way through the “big request.”

Success with the mere-agreement effect aligns closely with the idea of a “yes ladder”: developing camaraderie between you (or your company) and a user by asking questions whose answers reveal ideological similarities.

It’s an obsession with the word “yes” and a search for any question that gets someone else to agree with you, even if that agreement is inconsequential to the sale.

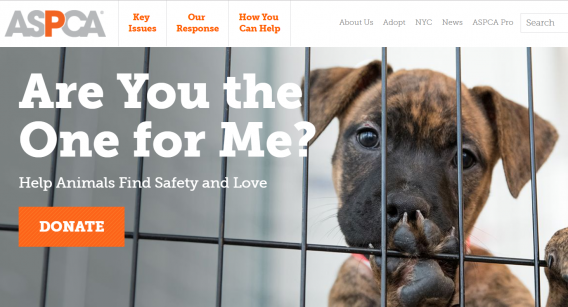

At its worst, It’s the painfully familiar tactic of telemarketers and infomercials. (“Would you like to lose 20 pounds without leaving the couch?”) But it’s also relevant for sites that benefit by building a sense of community based on shared values, a common goal in the non-profit space.

Many nonprofits have missions that, ideologically, enjoy almost universal support. Employing the mere-agreement effect takes advantage of this common ground—a nearly friction-free way to crack open the door.

Keys to applying foot-in-the-door principles

KlientBoost and other FITD experimenters have identified several keys to making FITD work on web forms. Related academic studies add nuance to the approach.

FITD works best when:

- Visitors are in the middle or bottom of the funnel. Those users are already engaged with your company and anticipate sharing more information. In contrast, a single-field email request usually outperforms multi-step forms for top-of-funnel offers like PDFs—users have no expectation of deeper interaction and, therefore, there’s no justification to extend the process.

- Visitors know they need to supply information to answer their question. No one expects a loan quote without providing some financial info. No one expects a house painter’s estimate without divulging basic details on square footage. A multi-step form works well if visitors believe that answering the first few questions is essential to solving their issue.

- The initial request is simple yet not trivial. A trivial request may fail to trigger the FITD effect—insignificant compliance means that the doer won’t register a change to self-perception. Researchers have shown that an unusual (but still simple) first task engages the mind sufficiently to trigger a self-perception change.

When foot-in-the-door may not work

The foot-in-the-door technique has counterweights:

- Door-in-the-face. Start with a large, unreasonable request to soften the perception of the subsequent request you actually want someone to accept.

- Foot-in-the-face. To maximize compliance, follow an immediate rejection with a secondary request—but wait two to three days if the initial request is accepted.

Debate over how to balance agreement and rejection isn’t limited to these techniques.

In Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton laid a foundation for negotiation strategy—one focused on reaching early agreement to catalyze later accord. Their perspective aligns well with the FITD technique and yes ladders.

It’s the opposite of what Chris Voss, a former FBI negotiator, argues in his book Never Split the Difference. The problem with “yes,” Voss contends, is that it cedes control, and no one is anxious to do so in a negotiation.

By demanding a “yes,” the self-perception and mere-agreement models of the FITD technique make an immediate—and ever-expanding—power grab. It’s one reason why FITD can fail; even a small request still asks for a “yes.”

Notably, however, the commitment and consistency model for FITD demands only initial engagement, not initial agreement.

And, based on Voss’s experience, it offers another potential way to sneak a foot in the door—using a “no” can simultaneously empower users and start them on a conversion process they’re loath to abandon.

Examples of foot-in-the-door failure

At KlientBoost, Dane learned early on that the wrong initial ask could negate the positive effect.

In his experience, anything that strips the visitor of anonymity is a risk. That includes some of the obvious asks—email, phone, etc.—but also semi-identifiable information, like a company name.

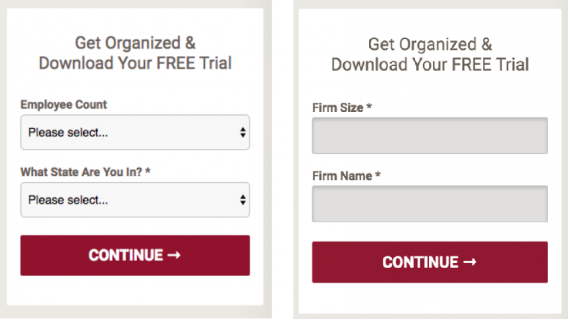

KlientBoost saw a 50% decrease in conversions when they used a company name field to start a conversion process instead of more generic information on employees and location:

MiroMind, a Toronto-based SEO agency, tested the FITD technique across several clients sites—in software, cloud services, SaaS, and health and beauty niches—and also saw form fills drop.

Their single-page versions generated 80 to 180% more leads, and as many as 70% of visitors closed the expanded forms as soon as they realized that they had multiple steps. Notably, the forms asked for an email address early in the sequence (to allow for follow-up with non-completers), which may have torpedoed efforts.

Conclusion

So how difficult or intrusive should your initial question be? How do you engage visitors without scaring them off? It’s an elusive balance that, like the FITD technique, requires testing.

Understanding the most relevant trigger for your site—self-perception theory, the commitment and consistency principle, or the mere-agreement effect—can help identify your initial question and guide the remainder of the sequence. Even Voss, despite advocating the power of “no,” is ultimately working toward a “yes.”

Take, for example, a question that might be a useful starting point to begin a conversion sequence on this post:

Do shorter forms always work better?

Hi Derek,

Thanks for sharing your analysis. I wanted to add that we are finding very similar results around the idea of breaking forms up into multiple steps. Based on 4 experiments, so far we’re finding a net +5% increase in general conversions. More of our research can be found under this pattern: https://goodui.org/fastforward/patterns/9/

Hope this helps,

Best,

Jakub

Thanks for sharing your research (and reinforcing the value of testing!).

Have you come across any tactical learnings that we don’t discuss above?

One of the things that really stuck out for me throughout was something Seth Godin loves to say, “people like us do things like this”. If you combine this with the sunk-cost effect, FOMO, relatable copy, and a conscience, it can accomplish quite a lot. Great read, thanks!

Thanks, John! As you note, there’s probably more than one psychological factor at work when it comes to why FITD is successful. Happy testing…