There’s a fine line between online persuasion and manipulation.

Most university classes, at least in the humanities and social sciences, dealt at least in partial with the morality of the lessons we learned. Especially in marketing and communications classes, there was the line between persuasion and propaganda.

Online, though, for whatever reasons, ethics aren’t discussed as frequently. Of course, we’re all in xthe business of persuasion, at least to the extent that we’d like people to buy our products. Nir Eyal put it well a while back:

We build products meant to persuade people to do what we want them to do. We call these people “users” and even if we don’t say it aloud, we secretly wish every one of them would become fiendishly addicted.

But, in the end, what differentiates persuasion from its more evil cousin?

Table of contents

The Facebook controversy: a contemplation of ethics

Not that ethics in experimentation has ever been very clear cut, but the internet has made things even weirder.

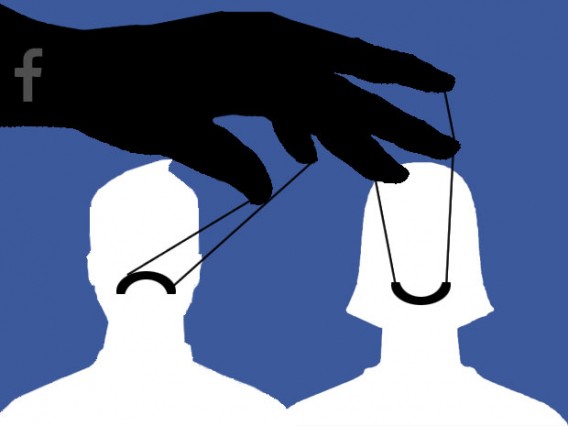

We all (hopefully) remember the Facebook scandal, where Facebook manipulated the content seen by more than 600,000 users in an attempt to see if they could affect their emotional state. They basically skewed the number of positive or negative items on random users’ news feeds and then analyzed these people’s future postings. The result? Facebook can manipulate your emotions.

As AV Club put it, “Result: They can! Which is great news for Facebook data scientists hoping to prove a point about modern psychology. It’s less great for the people having their emotions secretly manipulated.”

The publication of these results, of course, led to massive blowback. Though people signed off their permission for Facebook to do such a thing, it still came as a shock that they would test something like emotional manipulation on such a massive level. As such, it became one of the most salient discussions in online manipulation in recent memory.

What is “Skinner Box Marketing”?

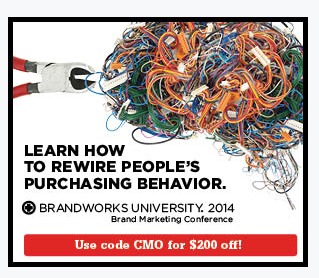

You remember B.F. Skinner from psychology 101? He conducted all sorts of messed up studies around ‘operant conditioning.’ Well, there are a few voices claiming that we’re entering a new age of Digital Skinner Box Marketing. According to The Atlantic, it’s essentially…

We’re entering the age of Skinnerian Marketing. Future applications making use of big data, location, maps, tracking of a browser’s interests, and data streams coming from mobile and wearable devices, promise to usher in the era of unprecedented power in the hands of marketers, who are no longer merely appealing to our innate desires, but programming our behaviors.

Joseph Bentzel broke the process down into three broad pillars.

Three pillars of Skinner Box Marketing:

1. Emotional manipulation as ‘strategy.’

According to Bentzel, “the emotional manipulation is always and often rationalized under the flag of ‘serving the customer.’”

2. The new ‘chief marketing technologist’ as that ‘man behind the strategy curtain.’

Bentzel:

On the surface, the ‘chief marketing technologist’ looks like strategic marketing progress in the digital age. But when you combine these powerful technologies with emotional manipulation as strategy—you’re getting pretty close to something more than a few folks see as unethical.

3. The ‘big data scientist’ as ‘skinner box management’ provider.

You need big data to fuel these insights. Therefore, Bentzel lists this as the third pillar of Skinner Box Marketing:

And not just any big data but the kind of big data that provides a 360 degree surround-sound view of the specimen in the digital skinner box, aka the consumer. The big data component of the skinner box data management model is now on the agenda at the big analyst firms. They call it ‘customer context.’

Digital market manipulation

The ascension of Skinner Box Marketing on the internet is backed by an academic concept digital market manipulation.

Market manipulation, the original theory, supplements and challenges law and economics with the extensive evidence that people do not always behave rationally in their best interest as traditional economic models. Rather, to borrow a phrase from Dan Ariely, humans are “predictably irrational.”

Digital marketing manipulation builds onto this theory, focusing on the dramatic capabilities of the digitization of commerce to increase the ability of firms to influence consumers at a personal level.

In other words, M. Ryan Calo posits that emerging technologies and techniques will increasingly allow companies to exploit consumers’ irrationality or vulnerability. Essentially, the internet makes it that much easier to exploit emotions on a personal level and manipulate actions.

Anyway, all of this is to say that companies can and have been manipulating consumers in a variety of ways. On the internet, these are most often referred to as “dark pattens.”

Dark Patterns, reintroduced

You’ve almost assuredly heard of ‘dark patterns’:

Normally when you think of “bad design,” you think of the creator as being sloppy or lazy but with no ill intent. This type of bad design is known as a “UI anti-pattern.” Dark Patterns are different—they are not mistakes, they are carefully crafted with a solid understanding of human psychology, and they do not have the user’s interests in mind. We as designers, founders, UX, and UI professionals and creators need to take a stance against Dark Patterns.

The holy grail of dark patterns examples is at darkpatterns.org. Check that out. They list 12 categories of dark patterns:

- Trick questions;

- Sneak into basket;

- Roach motel;

- Privacy Zuckering;

- Price comparison prevention;

- Misdirection;

- Hidden costs;

- Bait and switch;

- Confirmshaming;

- Disguised ads;

- Forced continuity;

- Friend spam.

Flip around the site and check out some of their examples. I know you’ll recognize these techniques and probably be able to find tons more examples.

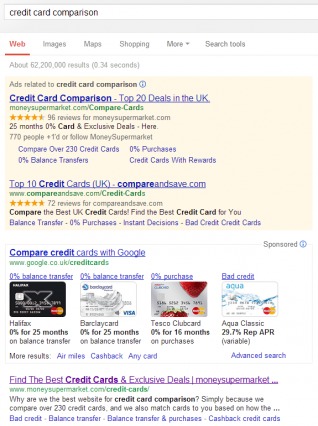

Example: Google’s disguised ads

As the SEO Doctor pointed out, even Google isn’t always so righteous in their practices. He gave two examples of their (possible) dark pattern of disguising ads.

Though I think the first one may be a bit exaggerated, the article gives the example of the deceptive background color of Google’s sponsored links. For example…

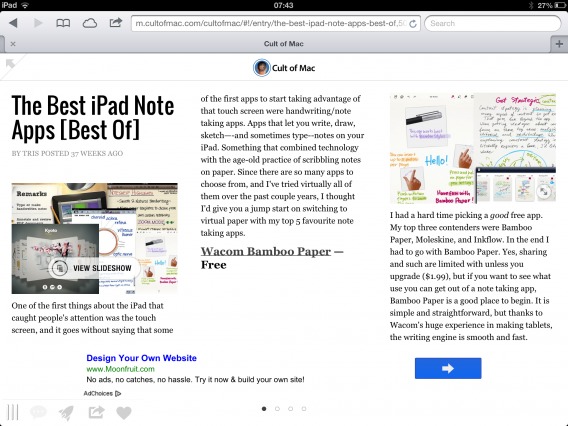

The second example I thought was a little more legitimate, because, well, I’ve definitely fallen for it many times.

SEO Doctor draws attention to the arrow box on Google’s display ads—you know, when you’re on a blog and there’s a button that looks as if it will send you to the next page. But, no. It’s a subtle ad.

Blackhat copywriting

Challenges of ethics are not new in advertising. Read any advertising history book to see the messed up tactics they’d use to manipulate readers. But, of course, manipulative copywriting still exists on the internet (and it’s probably easier to get away with it, too).

Instead of scouring the internet for bogus claims (of which there are many—check some out here), here are three very specific, and not often talked about, copywriting manipulations:

- Testiphonials;

- False scarcity;

- The damning admission.

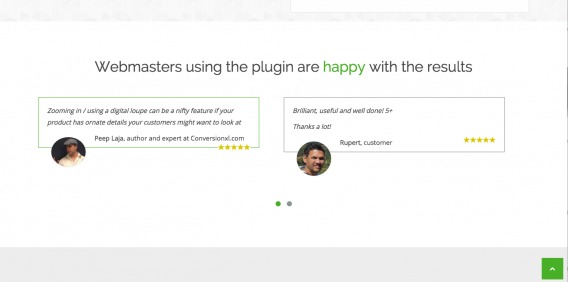

Testiphonials

You know not all testimonials are legit, right?

Of course they aren’t. Testimonials work more often than not in A/B tests (at least the trustworthy ones), but they’re not all done ethically. Take this one for example, where a company pulled a quote from a CXL article to get a fake testimonial from Peep:

Testimonials, when authentic or perceived to be authentic, boost the credibility of your offer by engaging social proof. It’s more common than you’d think for companies to fake or embellish testimonials. Keep an eye out for that.

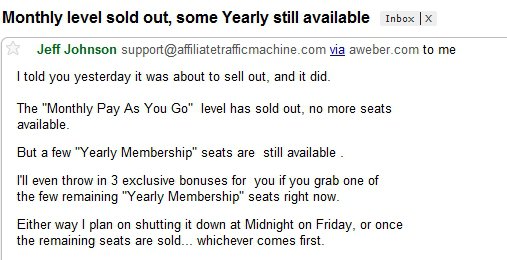

False scarcity

False scarcity is a pretty common tactic in online marketing. It’s also infuriating, and it can obviously backfire if the consumer catches onto it.

Peep wrote about this a while ago, giving the example of the following email he received:

Normally scarcity works (a pillar of Cialdini’s six persuasion principles), but when it’s deliberately forced like this? It screams sleazy. The email was referring to a digital course that, somehow, had sold out of monthly pay as you go levels, but still had yearly memberships available. Funny how that works.

The damning ddmission

This one is pretty common in infomarketing, but it’s been applied to more than just that field.

Basically, the damning admission is designed to lower the guard of the consumer and make your offer seems more authentic and credible. Here’s how White Hat Crew described it:

Just before making a claim that you want people to believe, you admit something negative about your product. By demonstrating your willingness to show your product in its true light, you gain credibility, and the prospect is more likely to believe your positive claim.

Of course, this technique can be used either to shine a more perfect light on the truth (to help people accept a true but exceptional claim that would usually be received with skepticism), or to manipulate (to trick people into accepting a false claim).

Your intent may guide your decision to use the technique or not, but it’s the truth or falsehood of the claim that determines whether it’s persuasive or manipulative.

As implied by the above quote, the damning admission isn’t always unethical. Heck, most of the time it’s an example of truly and authentically describing your product. But when one employs the strategy in order to legitimize a false claim that follows, it’s an example of blackhat copywriting.

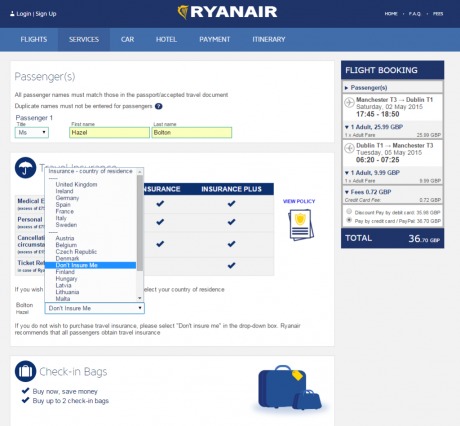

The power of defaults

The power of defaults? That’s something Jakob Nielsen wrote about about a decade ago in relation to search engines. Turns out, users almost always pick the top option (even when the top two options switch places). This leads to the idea that users overwhelmingly choose the default option in online decision making. Of course, many companies exploit this.

An example of this online comes from none other than Ryanair (via darkpatterns.org). They offer travel insurance but the free option to decline it.

Not only do you have to look in a list called ‘Insurance – country of residence,’ but the free option, ‘Don’t insure me,’ distinguished at all for easy access. They’ve placed it alphabetically between Denmark and Finland.

Negative option features

The power of defaults can be positive, but negatively embodied the tactic becomes known as ‘negative option features.’

These negative option features have been written about extensively by the BBB, Visa, and many others interested in deterring online deception. Here’s Visa’s description of a negative option feature:

Consumers accept an offer online, often for a “free trial” or “sample.” They provide their card information in order to pay a small amount for shipping. What they may not realize is that there is a pre-checked box at the bottom of the page in fine print or buried in the terms and conditions that authorizes future charges. Consumers are required to un-click or opt-out of a pre-checked terms and conditions or payment authorization box or cancel before the end of the trial period to avoid being billed a recurring monthly charge.

For free trials with a negative option feature, a company takes a consumer’s failure to cancel as permission to continue billing. Cancelling can also be complicated by merchants with poor customer service, slow response times, and untimely refunds.

Tricking you out of tips

For one last real world example, picture yourself purchasing a large latte at your local coffee shop.

When you go to pay, it’s now almost always done on an iPad. According to Nir Eyal, “digital payment systems use subtle tactics to increase tips, and while it’s certainly good for hard-working service workers, it may not be so good for your wallet.”

Again, the power of defaults.

First, by removing physical cash from the equation, they remove many barriers to tipping. For example, what Dan Ariely coined as the Pain of Paying is no longer applicable. Also, leaving a tip on the digital system is easy—equally as easy as it is not to tip. Here’s how Nir Eyal put it:

Nir Eyal:

“When cash was king, anyone not wanting to give a tip could easily leave the money and dash. “Whoops, my bad!” However, with a digital payment system the transaction isn’t complete until the buyer makes an explicit tipping choice. Clicking on the “no tip” button is suddenly its own decision. This additional step makes all the difference to those who may have previously avoided taking care of their server.”

Another way they increase our tip amounts is by anchoring. At a coffee shop it may be the worst, because you’re likely to purchase less than a $4 cup of coffee. The three options you’re usually presented for a tip on the screen are $1, $2, and $3 (and a custom amount).

Because of the anchoring effect, we’re drawn to pick the middle option, even though that’s a large amount more than the suggested tip percentage. Nir Eyal gave an example of his taxi ride to explain this:

Nir Eyal:

The vendor knows you likely won’t pick the least expensive amount—only cheapskates would do that. So even though 15% is squarely within the normal tipping range, by making it the first option, you’re more likely to chose 20%. Picking the middle-of-the-road option is in-line with your self-image of not being a tightwad. Therefore, you tip more and you’re not alone. The New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission reported tips increased from 10% to 22% on average when the new payment screens were turned on.

Note: this isn’t an example of online manipulation, but rather an illustration of the power of defaults. If anchoring and defaults make it easy to increase physical tips, then think about this example next time you’re confronted with a pricing decision online.

Conclusion: the blurred line of right or wrong

So online manipulation exists, clearly. What, then, do we do about it?

A common answer might very well be: “Caveat Emptor (let the buyer beware).”

That, however, places a lot of responsibility on the irrational side of the consumer’s mind. That’s where knowledge (via articles like this and archives like darkpatterns.org) comes in handy; if you can detect deception, you’re more likely to avoid it.

Then there’s the question of the difference between manipulation and marketing, which I never really answered. That’s a tough question for anyone to answer. I like Roger Dooley’s answer to it, though:

Roger Dooley:

“My response to the “manipulation” question is always, “If you are being honest, and if you are helping the customer get to a better place, it’s not manipulation and it’s not unethical.”

In today’s age of enforced transparency for business, manipulative tactics that deceive the customer simply won’t work. They will be quickly exposed and, with consumer voices amplified by social media, cause far more damage to the business than any short-term benefit.”

There are certain tactics here that are used prevalently by large companies, but are by a large majority viewed as unethical. Therefore, dark patterns and online manipulation is a complex ethical decision, one that hinges on the balance between doing what’s right and doing what’s effective.

Working on something related to this? Post a comment in the CXL community!

Hey, Alex,

Like always you’re surprising us with something worth reading (and sharing).

I totally agree that manipulation exits. It’s been around since advertising started to shape human behavior…or even earlier. I think that like everything in life, marketing can make harm or good.

Cheers!

Hey Elena,

Thanks for the comment – I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

I studied advertising in college, and I felt like half of what we discussed was ethics and the history of advertising, a lot of which – especially early on – was littered in deception and puffery.

Online deception is a fascinating topic all on its own though. Darkpatterns.org is a super interesting archive of the crazy stuff companies do to deceive, highly recommend perusing that site for a while if you’re interested.

Cheers,

Alex

Hey CXL,

Nice write up. Here is a philosophical question pertaining to False Scarcity and dark patterns in general.

On your very own awesome conference, https://live.cxl.com, aren’t you creating a sense of false scarcity by opening and closing the tickets in phases, instead of making them available all at once? I’m sure you can easily go on the defensive, but I still think it has a “degree” of “darkness” in it due to the artificial nature of restricting sales.

Here is my point, and I really don’t mean to rain on your parade. Please don’t think this is some attack. :) Recently, I’ve been thinking that the whole idea of “dark patterns” focuses way too much attention on the method of delivery, sales and interaction, and forgets to involve the good/ill intention of the product itself. I’m thinking that if the product is well-intention (and in your case because it’s an awesome conference, I believe it is), then that overshadows the method of persuasion that is used. Essentially, I’m beginning to think that if the product is awesome (or has net good will), and when customers after having purchased the product will thank you for it in the end, then false scarcity (and maybe other “dark” patterns as well) get the green light to be used.

Maybe another classic example tied to this is the default opt-out law of organ donation in some European countries (essentially people are organ donors by default unless specified otherwise). Some might say that opt-out is baaaaad to the bone, but in this case it saves lives. In such situations, dark patterns begin to mean less and less to me.

On the flip side, when we engage in optimization projects, we often run into companies that try to sell stuff that we sometimes conclude should not be sold at all (weight loss pills with no scientific backing, day trading accounts against the reality that most common people will lose their hard earned money, and the list goes on based on a personal level of ethical beliefs). In such cases, dark or light patterns don’t matter as much. The product itself disqualifies the optimization project, because we would not be able to sleep at night knowing that we raised sales by x% for such a company. And there are so many more dark companies out there than the oversimplified/popularized view that it’s just the cigarette industry.

So yea… false scarcity all the way, Peep! Because it’s a kick ass conference and people will thank you for it. :)

Thoughts? :)

It’s not fake scarcity. Putting on conferences is *very* expensive, and we need the support of event partners to make it happen. So by giving our partners an exclusive time window to offer tickets to their network we can add more value to them.

Dark pattern is getting people to do something they didn’t want to do, that’s the official definition. Organ donorship defaults are not a dark pattern, also due to the good cause involved.

Dark patterns aren’t getting someone to do something they don’t want to though. They are getting people to take an action without knowing they are taking that action or have control over said action.

Good sales and marketing teams convince people to do things they don’t want to do every day, it’s a value proposition that requests people to decide if the good or service is more valuable than the currency it costs.

Noone wakes up and says, I want to spend x amount of money on a conference today, but because the value add is so great, we do something we don’t want to do, give you a couple grand to be informed and enlightened.

A subtle difference, but I think its important to note.

I agree with you that it’s often much more important to take into account the good/ill will of the company/product/service, instead of the ethical or unethical marketing of that product. This actually informs the murky debate around ethics that has been going on since the inception of modern advertising.

However, Peep is right about the conference. It’s not fake scarcity, mainly because there ARE a limited number of tickets. Also, event partners allow us to mitigate the high costs of putting on such an event, so closing tickets to let them offer tickets is an operational necessity instead of a dark pattern.

While conferences are expensive to organize and just as expensive to attend (and thus more often than not a complete waste of time that is sold on the “need to network” the “loss of sales if one doesn’t attend” and the “loss of status if we’re not there”), I can think of very few conferences that have the luxury of not having either its vendors or attendees making last minute decisions to attend. If there are enough attendees then the organizers say, “hey, look at all these fish swimming around in this barrel we just created for you… if you don’t secure your space now [and here’s the places where most of the foot traffic flows toward], you’re going to lose out. Don’t be a sucker [sucker]”.

I also don’t understand why we continually create all these false dilemmas in articles like this who use certain “gurus” as all-knowing… Dan Ariely is a smart guy but his book is almost like some joke he is playing on the buying public simply by injecting the word “irrational” into the equation. One academics ‘irrational’ can usually be explained as “quite rational” by another. There are many studies Ariely cites in his book, such as “the endowment effect” that have been disputed by other academics in peer-reviewed processes. I’m not sure things like “Dark Patterns” rises to that level (though I do enjoy reading their “stuff”).

Finally, one of the commentary questioned whether or not Roger Dooley’s metric on ethical usage of persuasive marketing techniques, and while I agree with the commentator’s point that we should not create another false dilemma by saying Roger Dooley is an authority on the subject of ethics (though I’m sure he’s a man of high integrity based on the limited things I have read) it does make more sense that the pursuit of making our customers’ lives better and more productive should be a good enough standard and for the most part then the end does often justify the means…

Afterall, isn’t it the role of the clinical Psychologist all about getting someone to think in a different fashion? Isn’t that what we are talking about… the Psychology of Sales?

Big data is great, and I like that the author acknowledged the need to have all the data and a “360 view” of that data, but, really folks (and this is the problem with all those who tell you and me they have some “algorithm” that can predict behavior) the best we can hope for at this moment is knowing what really happened in that data set (Johnny went to the mall… Not Johnny went to the mall to buy a jacket), and we’re certainly not capable of predicting conditions that will repeat what was seen in that data set in some future world…

Yes, I agree that online manipulation still exists and many have become successful in doing it. Why? They do it with subtlety and untraceable. It looks legit, as if they are not deceiving the viewers. However, I would also like to agree that once detected, it could easily destroy the reputation of the business. We build trust. Once we win our customers’ confidence, we should value it. It may look effective at first, but the rebound can hurt you and your business eventually.

Thanks,

Carl Ocab

http://www.carlocab.com

Hey Carl, thanks for the comment.

I agree totally. That’s why sites like darkpatterns.org are cool – give people the heads up on who’s doing unethical stuff.

Roger’s quote summed it up well for me:

“In today’s age of enforced transparency for business, manipulative tactics that deceive the customer simply won’t work. They will be quickly exposed and, with consumer voices amplified by social media, cause far more damage to the business than any short-term benefit.”

I think the worst one of all of these manipulations is the fake testimonials. I constantly see ads for people who will write fake testimonials on places like fiverr.

I experienced this when I was looking to buy a light that had been a kickstarter at one point, it had some 1500 amazon reviews, which seemed a bit high considering the light had only been released a month prior. I googled some of the review text and found the exact same testimonial on about 5 other products. I was completely disgusted and refused to purchase the product.

Testimonials are probably the ones that worry me the most as well. I feel like I lean fairly heavily on testimonials in purchasing consumer goods from places like Amazon.

To think that they are now increasingly being tainted lessens their weight on me, and leaves a void in my purchasing process. I can see myself and others suffering because we cannot tell how to purchase quality goods/services anymore. Troubling for sure!

Fake testimonials are so much more common than I would have thought a few years ago. I, too, lean heavily on Amazon reviews, and try to view them more critically now that I know it’s easy to game the system.

As a marketer for a job hunting platform, I’m constantly left wondering whether I too should bloat numbers and testimonials like competitors do in their ads. Say, they bloat up their stats such as applicants or interviews conducted, etc. Till now, I’ve always resorted to honesty, but it’s very tempting to step into the other side.

Thank you for this enlightening post.

“If you are being honest, and if you are helping the customer get to a better place, it’s not manipulation and it’s not unethical.” Is mister Roger deciding what gets the customer to a “better place”? The customer? The experience with the product? Bah…