Get a chicken. Cook it until it’s perfectly done. Reduce the jus to a nice pan sauce. Then finish it with some butter until it has the right balance of flavors. Enjoy.

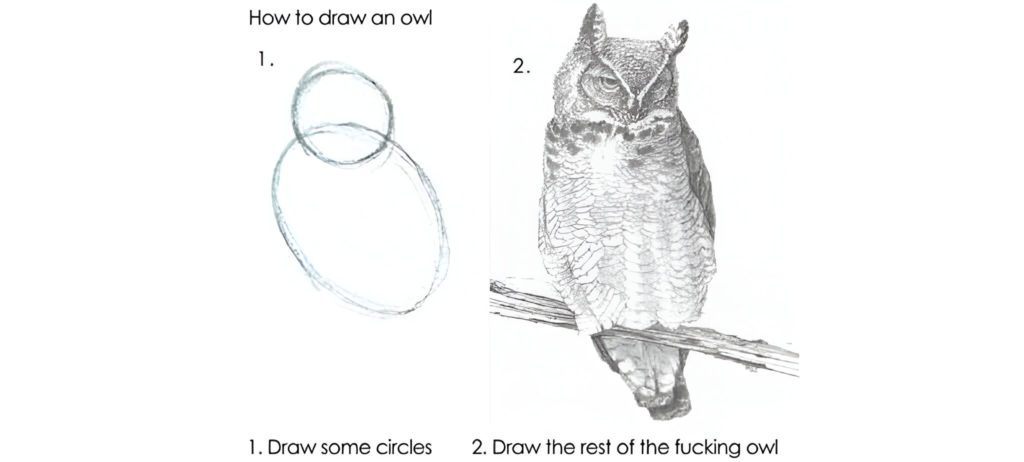

This is a useless recipe, but it’s not wrong. It assumes, however, that accurate advice on what you should do is as valuable as advice on how to do it—the “Should-How Fallacy.”

But being right doesn’t create value; empowering others to succeed does.

When it comes to content marketing, all the branding and differentiation (and money) is in the latter. But most content resembles the former.

So how do you get content to where it should be?

Table of contents

The difference between “should” and “how”

“Should” can look damn good. A novice can churn out a comprehensive list of best practices that tells you exactly what you should do—without helping you do it.

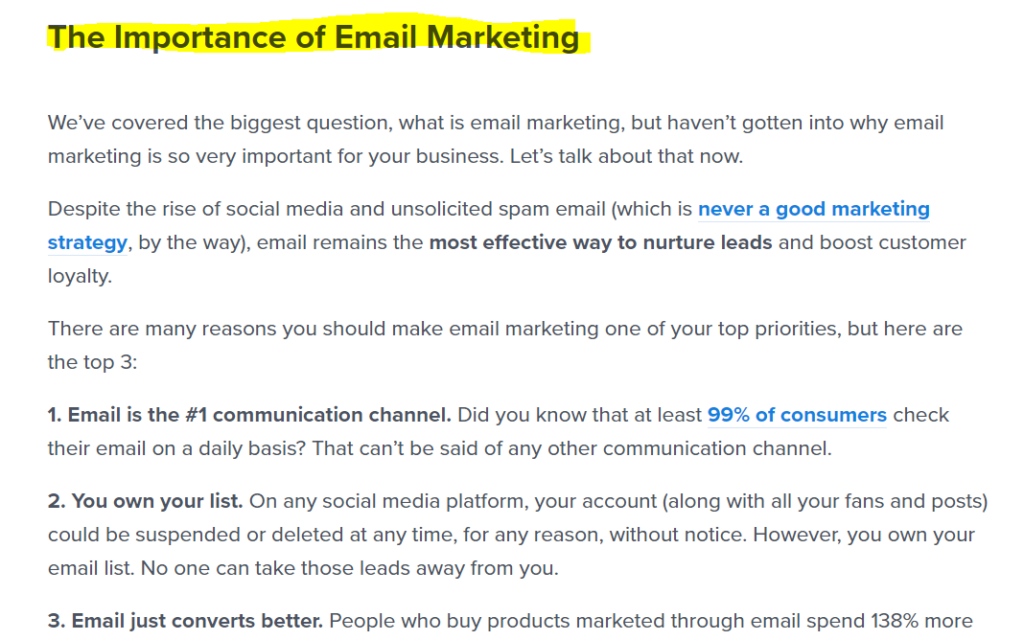

Take this snippet from an “ultimate guide” on delighting customers:

Empower your potential and existing customers with educational resources, recommendations, and tools for success to build your brand’s inbound experience. You can do this by writing helpful blog posts, sharing tips on social media, and creating a self-service knowledge base.

All correct, all useless.

“Should” content also tends to focus on the “what” and “why” components, which pad word counts (and appease search engines) but achieve little else.

Most of your audience arrives on your site aware of what they need to fix. They don’t need you to define a strategy or tactic, or to tell them why it matters. (And if they do, they don’t need 2,000 words to be convinced.)

They need you to show them how to do it. Or how to rethink it—“how” content doesn’t have to be hyper-tactical.

The before-and-after of consuming your content should change at least one of three things:

- The way someone does something.

- The way someone thinks about something.

- The way someone feels about something.

The first two are more familiar to B2B marketers; the last one often applies to B2C. (Exceptions abound.)

In any case, ask, “What’s the combined delta of the content I’m creating?” How much will this sentence/paragraph/article change someone’s process, perception, or attitude?

So why is “should” content so ubiquitous?

Because it’s cheap to produce. Even a below-average generalist can pillage Page 1 of search results to piece together an academic overview. For well-funded companies, it’s a quick way to build a content machine that publishes three or four long-form articles a week.

That type of content ticks all the boxes that search engines—most companies’ dominant distribution channel—reward. Google won’t give you credit for nuance or expert takes that counter conventional wisdom. Novel metaphors don’t improve rankings.

But all the long-term value is in the “how.” And that’s where my brain has been the past several months.

Distilling marketing content, then distilling it again

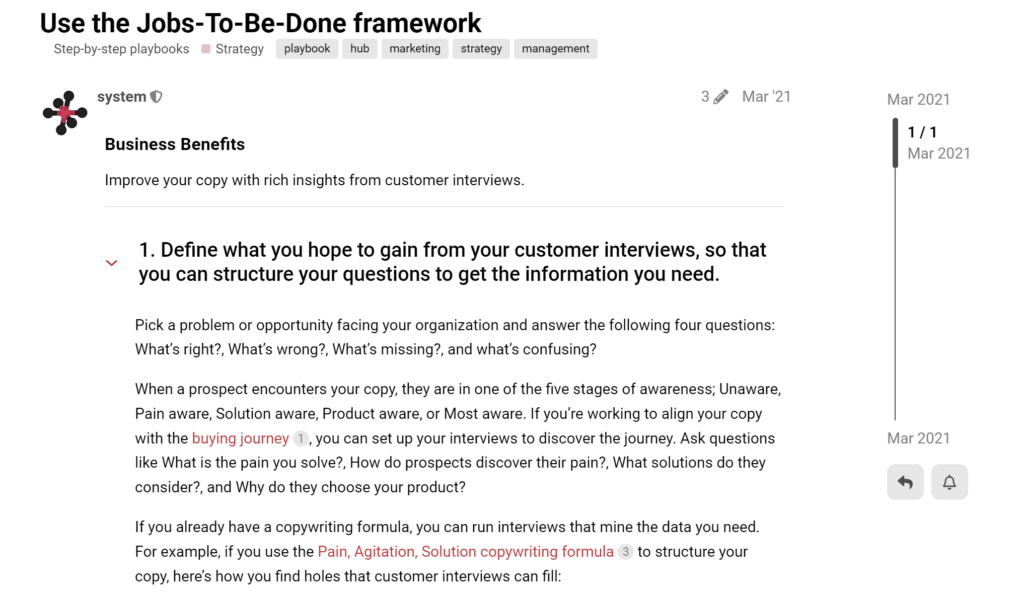

I worked with CXL on their Playbooks, which are marketing knowledge distilled into checklist-style step-by-step guides (a neurotically meticulous version of what we strive for with the CXL blog). We wanted to turn water into wine grain alcohol.

By helping develop the playbooks process (yes, it was hard), I became hyper-sensitive to wiggle words, the specifics that novices tiptoe around, and how experts unknowingly build assumptions into their workflows.

It reminds me of the apocryphal story about Michelangelo unveiling his sculpture of David. “How did you create such a masterpiece from a crude slab of marble?” asked an admirer. “It was easy,” Michelangelo responded. “All I did was chip away everything that wasn’t David.”

We chipped away every word that’s not a playbook. We haven’t ushered in the High Renaissance of marketing content (yet). But what I’ve learned—at CXL—has made me pretty handy with a chisel.

5 keys to money-making, how-focused content

The five lessons below are as valid for action-oriented content as they are for thought leadership, for lengthy ebooks, or pithy tweets.

1. Experts aren’t best-practice repositories—they tell you what happens when you try to implement best practices.

You don’t see a nutritionist to ask whether a salad or deep-fried Oreo is the more heart-healthy choice.

So why would you ping Peep to ask for his “best CRO tip”? Or Kaleigh Moore to ask if freelance writers should network?

Advanced, thorough research of best practices—all the things someone should do—is the base upon which experts offer contrast and depth. Experts explain what it’s like to actually do the work—stories of the real-world how.

- Ask Peep: “Which CRO ‘best practice’ do you disagree with most?”

- Ask Kaleigh: “What’s the most underrated networking channel?”

With the CXL Playbooks, this led us to a layered editorial process. Why ask Aleyda Solis to write a playbook on Hreflang tags when a freelancer could get it two-thirds of the way there? It would be boring for her and wasteful for us.

If I’m paying for an hour of Solis’s time, I’d rather have her review a dozen playbooks—sharpening instructions, adding caveats—instead of copy-pasting known best practices.

For long-form content, the principle is the same. For example, when we sent out an interview-style survey for a CXL post on how to build an agency, we asked questions like:

When you have that depth of source material, expert voices carry the narrative. This makes your job easier. Fit the responses together, sand the edges between them, and you end up with expert-led, how-focused content.

2. Examples are windows into the “how.”

Say you’re writing about how to marry Google Analytics and CRM data. Readers could use any number of CRMs. While you could write dedicated posts to cover the five or 10 most popular, that probably won’t make sense (too much overlap, limited editorial resources, etc.).

So what do you do? Pick one.

Examples act as glass-bottom boats—all-the-way-to-the-bottom visibility for whatever you’re talking about. For instance, with the CXL Playbooks, we have steps that require a tool, but any one of many might work.

A step in a CXL playbook could read, “Use a scroll-tracking tool to see how far users go down the page.” Okay, but which tool should I use?

You’re not going to list the 20-odd tools someone could use, but you can add a couple of examples: “Use a scroll-tracking tool, like Hotjar or Lucky Orange, to see how far users go down the page.”

You’ve given users a shortlist of vetted options (the Wirecutter model) as well as ready-made queries for independent research (e.g., “alternatives to hotjar”).

The same applies to instructions that rely on opaque, catch-all terms:

- “Segment your audience based on key factors.” (Such as…)

- “Segment your audience based on demographics like age, gender, and location. (Ah, got it.)

The list isn’t comprehensive, but it orients me. It sets expectations. It helps me graft your process onto my own.

The technique to swing a baseball bat is different from the one for a tennis racket or golf club. But walking through one process clues you into what’s involved in others—the rough number of steps, the core body parts involved, and the piecemeal drills that help you put it all together.

3. Imperatives damn well better inspire action.

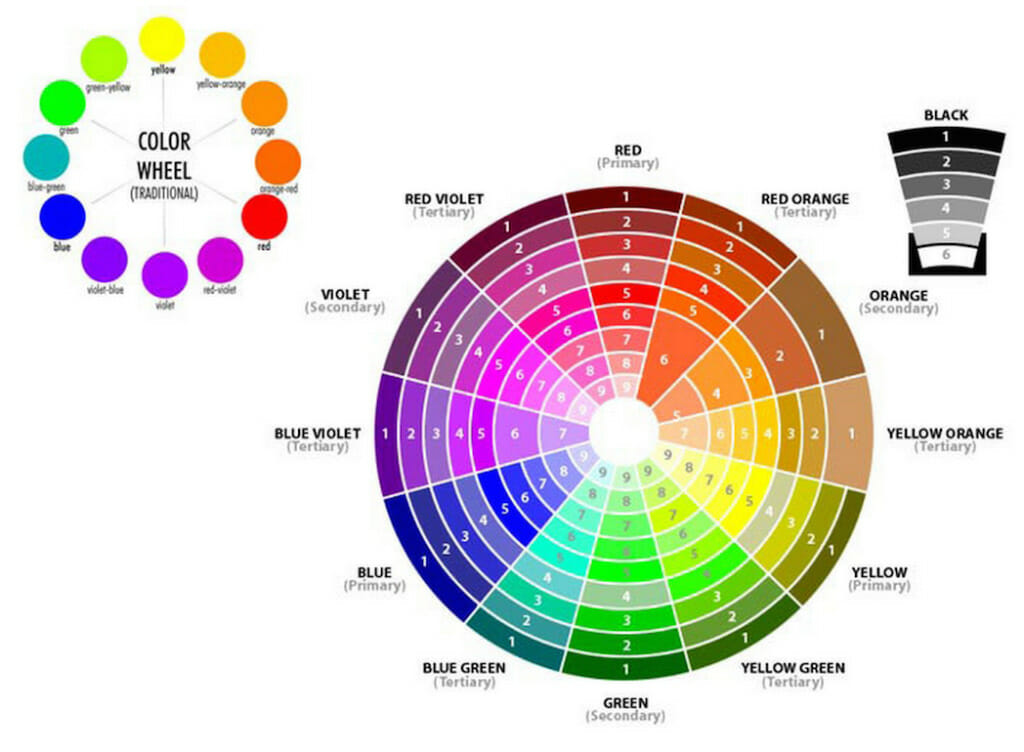

“You need to,” “Ensure that, “Be aware”—these are all should phrases. People usually know that they “need to use a high-contrast button color.” They don’t know what qualifies as “high contrast.”

If you can identify a high-contrast color by picking something on the opposite side of a color wheel or by choosing similar colors with a saturation gap of more than X%, then tell people to do that.

Other imperatives, like “Analyze,” “Consider,” or “Understand,” are all verbs for which the thing you’re supposedly doing is in your head.

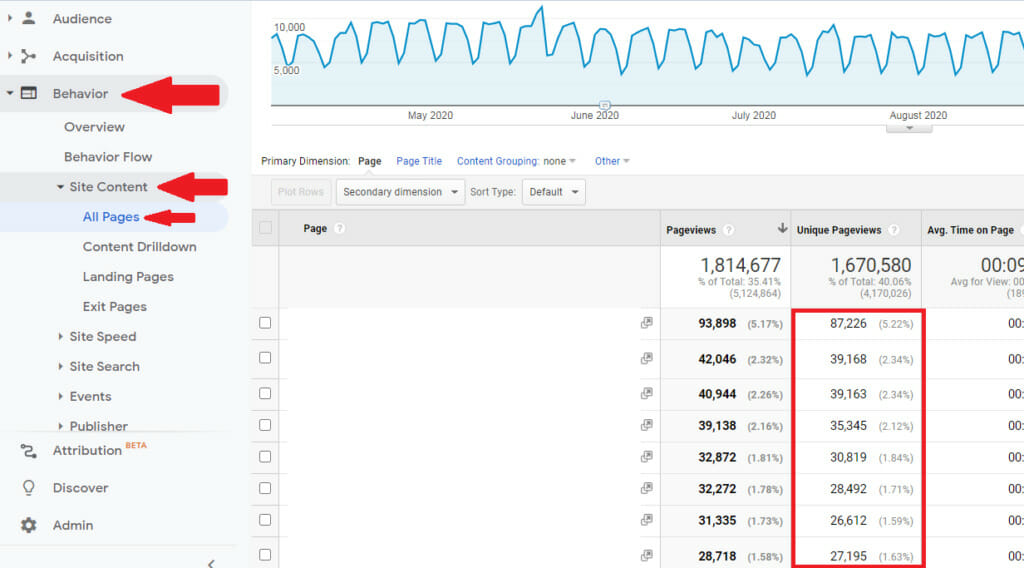

If you tell me to “analyze my traffic sources,” what am I doing? Staring at my monitor and awaiting an epiphany? If the purpose of the analysis is to identify top traffic sources, a much clearer step is “Identify your top two traffic channels in the Google Analytics ‘Acquisition’ report.”

A common step and step explanation in the CXL Playbooks before editors get to it:

What the “after” looks like:

Taking it a step further, what is the outcome of the analysis? What will someone do with that knowledge? The purpose of digging through analytics rarely stops at personal awareness.

The solution is to skip ahead to the outcome and assume the between-the-ears task:

- “Add the top two traffic channels in the Google Analytics ‘Acquisition’ report to a Google Sheet.”

That’s a long way from “Analyze your traffic sources.”

4. Adjectives and adverbs signal missing information.

Experts unknowingly build assumptions into their knowledge-sharing with adjectives and adverbs. Novices use them to feign expertise—to assume that you can assume because they have to assume (because they do not know).

For example, adjectives are killers in this draft of a playbook step on sourcing quotes from HARO:

- “Be very specific when you put out HARO requests to ensure you reach relevant contacts.”

All the how-to is hiding underneath those adjectives. (How do you win a presidential campaign? Run the best campaign. Boom. Done.)

For CXL Playbooks, we might rework the step into:

- “Qualify HARO respondents by including prerequisites, like industry, job title, or years of experience, in each question.”

That tells people how to create “very specific” requests that reach “relevant” contacts. (Note that examples play a role, too.)

These subtle differences matter. If I ask you about your “best performing” content, you may be lost (if you’re new to the field). Or you may think I’m asking about traffic. Or shares. Or form fills. Or sales-qualified leads.

Chuck the adjectives and get to the click-level instructions. See this example with the plain ol’ Universal Analytics:

- Bad: “Use Google Analytics to identify your best-performing blog posts.”

- Okay: “Use Google Analytics to identify blog posts that receive the most traffic.”

- Good: “Use Google Analytics to navigate to Behavior > Site Content > All Pages and sort blog posts by unique pageviews.”

- Great: “Open the Behavior > Site Content > All Pages report in Google Analytics, then list the 10 blog posts with the most unique pageviews in a spreadsheet.”

You can’t write the “good” or “great” versions unless you’ve done it yourself. You can publish the “bad” or “okay” versions all day without ever having opened Analytics (or, on the flip side, after having opened it a million times).

5. Don’t do this (yes, this).

A decade ago, I was coaching soccer. I remember reading a (now forgotten) book by some famous coach. In it, the author noted that players can’t not do something:

- “Don’t give away the ball.”

- “Don’t get caught out of position.”

These tell someone what they shouldn’t do. Your job—as a coach or marketer—is to provide solutions:

- “Play one- and two-touch passes.”

- “Let the other center back know where you are if she has her back to you.”

Those instructions take you from “describing a bad job” to “explaining how to do a good job.”

A blog post on content writing that tells someone, “Don’t write a lengthy introduction,” doesn’t get them closer to success. And yet you see it all the time—a call not to do it followed by paragraphs about “why it’s important to be succinct” or the percentage of readers who skim articles.

Give actionable steps:

- Write your introduction after you’ve written the rest of the article.

- Make it two or three paragraphs long.

- Set expectations with 3–5 bullets about what the reader will learn.

That, there, is the start of a playbook.

(Too prescriptive? Maybe. But it’s infinitely easier for someone to riff off a complete, structured process.)

Conclusion

“Should” content is a temptation for those whose primary benchmark is, “Will this rank?” But we’re all vulnerable, especially when we’re creating content outside our niche.

So, if your advice starts to list more best practices and tell fewer stories, if adjectives come to mind before actions, if your recommendations don’t translate into mouse clicks, know that you’re probably outside your niche—and will struggle to create how-focused content.

Your niche may be smaller than you think. I can’t claim “content marketing” as mine, for example. I’ve never hosted a podcast or published a book or done a million other things that content marketers do. But I could plant a flag on running a blog or doing data-driven content research.

Alternatively, if you find someone who, no matter the topic, is convinced they’re still a master, then you have one of those useful examples—a window into the murky depths of the Should-How Fallacy.

Bad: “I should leave Derek a blog comment to show my support for this piece.”

Good: “I will leave Derek a blog comment with some things I liked about his article.”

Great: “Derek, I appreciate the thoughtfulness and immediate utility of your point about eliminating ‘should’ phrases from my work. The advice is spot on and I’ll refer to this often as I outline my next big article about shifting consumer search trends in the banking industry.”

I love it. Thanks!