How do people view search results? The answer to this questions brings great insight to those trying to make money on search marketing, whether SEO or PPC. We conducted a new eye tracking study to find out.

Table of contents

- The Ever-Evolving SERPs

- How Did Users View Google Search Results in the Past?

- How does this compare to our results?

- Does The F-pattern Still Hold True?

- How Do People View Ads

- Google Vs Bing: Significant Differences?

- There is a significant difference between how quickly users looked at rich text depending on whether Google or Bing was used.

- It took users significantly longer to begin exploring the search results “below the fold” on Bing than on Google.

- Users spent significantly more time viewing the search results page “above the fold” when using Bing compared to Google.

- Similarly, users spent significantly longer viewing the first 5 search results when using Bing compared to Google.

- It took Bing users significantly longer to view the first organic search result compared to Google users.

- Users spent significantly longer looking at the first organic search result and significantly less time looking at the first ad search result on Google compared to Bing.

- Conclusion

There have been a few eye-tracking and mouse-tracking studies done on search behavior in the past. Of course, you’re probably familiar with the F-Pattern uncovered by NN/g years ago.

However, SERPs (search engine results pages) are evolving quickly, and so is user behavior in relation to search.

So, as part of brand new research arm – CXL Institute – we conducted our own eye tracking study. We wanted to see if previous research still holds up.

For our study, we used a sample of 71 users for Bing and 61 users for Google. Industry standards (via NN/g and Tobii) suggest a sample of 30 people for valid heatmaps. However, since errors will occur with certain participants (looking away from the screen, etc), we wanted enough data with the errors thrown out, so we processed more than enough to get us at minimum 30 sets of eyes.

The Ever-Evolving SERPs

Google and Bing are constantly changing their interface. The goal, of course, is to provide the greatest possible user experience with the most relevant results. If users reach their goal faster, and are satisfied with the content the SERP delivers, they’re more likely to return and bring that sweet ad revenue to the company.

Let’s take, for example, the proliferation of rich snippets, the additional content other than the black text and link that call your attention to a results. These are things like reviews, photos, phone numbers, etc.

They’re thought to be highly effective at calling attention to a result and to provide a good user experience, but recently Google has mentioned that they don’t want to clutter results with too many rich snippets

As Zineb from Google posted on Twitter, “enfin, nous essayons de ne pas trop “encombrer” les SERPs avec trop de sites avec RS. Du coup, vos critères sont à évaluer.” (That translates to “Finally, we try to not “clutter” the SERPs with too many sites with RS. Suddenly, your criteria are to evaluate.”)

Point is, things change. So we looked at some past studies to compare to our results. Here are a few things we’ll touch on in the article:

- How Do Users View Google Search Results, Now vs Then?

- F-Patterns and Gutenberg Diagrams: Do They Hold Up?

- How Do People View Ads?

- Google vs Bing: Significant Differences?

How Did Users View Google Search Results in the Past?

In 2014, Mediative did an eye tracking study on 53 participants who did 43 common tasks. They compared the results with results they had gotten from a similar 2005 study:

Writing about the study, MarketingProfs’ author Nanji said, “the top organic result still captures about the same amount of click activity (32.8%) as it did in 2005. However, with the addition of new SERP elements, the top result is not viewed for as long, or by as many people. Organic results that are positioned in the 2nd through 4th slots now receive a significantly higher share of clicks than in 2005.”

How does this compare to our results?

The top organic search result still receives, by far, the most clicks of any organic search result (20.69% of all clicks on Google). The closest to that is, oddly enough, organic result #3, with 6.897% of clicks. However, rich data now gets 39.655% of clicks, by far the largest share.

While there was a big difference in what users clicked on (1st vs 3rd vs 2nd), there wasn’t much of a difference, on Google or Bing, on how long users fixated on each organic result:

Does The F-pattern Still Hold True?

Web optimizers and researchers are usually at least somewhat acquainted with Nielsen Norman Group’s F-pattern theory based on their 2006 study and article. The idea that you can slap an uppercase letter onto a webpage to solve all your design problems sounds good, certainly looks good, and for a while it probably was good.

We’re here to say that the F-pattern is no more. The evolution of search engine results pages has caused a similar evolution in user behavior patterns. The strict F-pattern style we saw before is, quite frankly, outdated

Here’s what the old F-Pattern looks like:

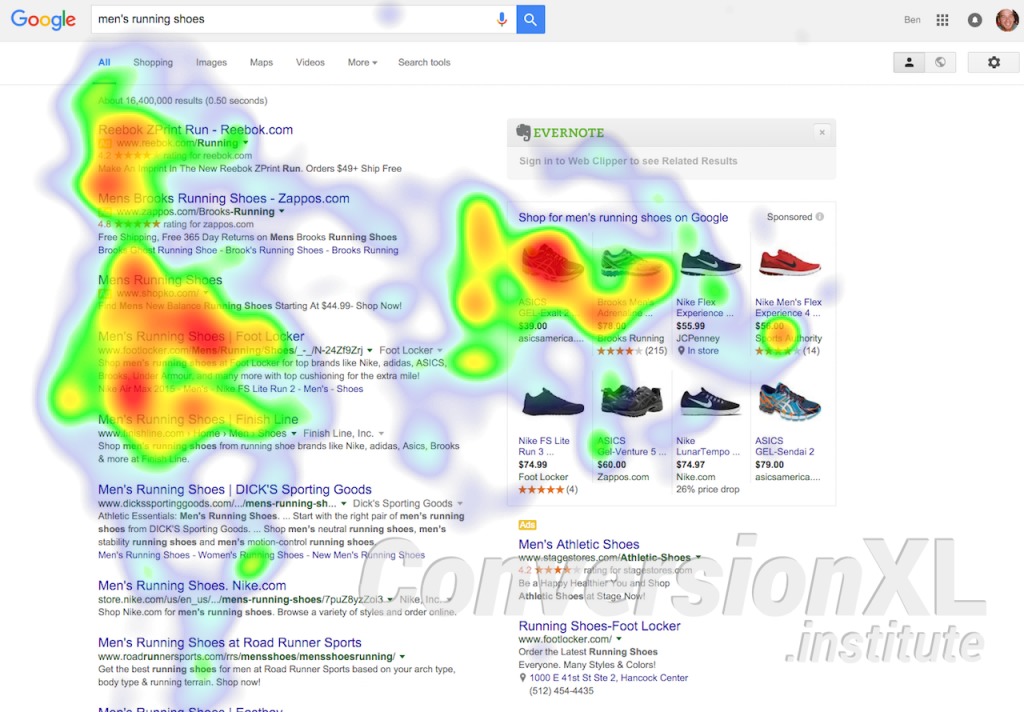

With the advent of rich text and ad placement, users find themselves exploring the entire results page to find what they’re looking for. As we observed through the Google platform, many users look at rich text on the right before even considering actual search results. Unfortunately, there is no longer a letter in the (English) alphabet to describe this new pattern:

You can also see the F-Pattern from a 2009 Google study with 34 participants:

But we simply didn’t see that in our data, even though we did the same task (we had 71 users search for ‘spanish water dog’):

How Do People View Ads

It’s true – ads positioned on the right don’t get much love.

Their position on the search results page simply won’t allow for it, they’re in a bad part of town.

However, when it comes to ads cleverly designed to look like top search results, users can’t help but look even if for only a moment. When the hoax is up, though, users quickly leave the paid search results behind for organic ones. The fact does remain that they’re looking at those paid results, though, and right away.

When it comes to how long users spend looking at ads, there’s no significant difference between right sided ads and paid search result ads.

One thing that popped out in the data is how much more common it was for users to click top ads on Bing. 19.118% of clicks were to the top ads on Bing, compared to only 6.897% on Google.

This all being said, it will be interesting to see how Google’s decision to stop showing right sided ads will affect user behaviors.

Google Vs Bing: Significant Differences?

Some of our findings can influence how you approach PPC and SEO; some of it is simply interesting, especially regarding the differences between Bing and Google. Here are some things we found…

There is a significant difference between how quickly users looked at rich text depending on whether Google or Bing was used.

Users began to view and consider rich text significantly more quickly when using Google than Bing. (Users looked at rich text after approximately .75 seconds while using Google. On Bing, it took them about 1.3 seconds to view the rich text)

It took users significantly longer to begin exploring the search results “below the fold” on Bing than on Google.

Users on Google began to view search results below the fold after around 7.1 seconds. When on the Bing search engine, users didn’t get around to exploring results located below the fold until around 10.5 seconds.

Users spent significantly more time viewing the search results page “above the fold” when using Bing compared to Google.

On Bing, users spent around 9.8 seconds looking at information above the fold, while Google users only spent an average of 7.8 seconds above the fold.

Here’s Bing:

And Google:

Similarly, users spent significantly longer viewing the first 5 search results when using Bing compared to Google.

Users on Bing spent an average of 4.5 seconds focusing on the first five search results. Google users only spent an average of 3.4 seconds considering the page’s first five results.

It took Bing users significantly longer to view the first organic search result compared to Google users.

Google users viewed the first organic search result around 3.3 seconds into their search experience. It took Bing users approximately 8.8 seconds to begin considering the first organic search result.

Why?

It seems unlikely that Bing users were simply exploring other elements of the page first due to the fact that most Bing users looked at the search results before any other element on the results page. Google users, who typically viewed rich text before the search results, still managed to beat Bing users to the first organic search result by five seconds. Perhaps computer users are less familiar with Bing and need time to figure out what’s an ad and what’s not.

Users spent significantly longer looking at the first organic search result and significantly less time looking at the first ad search result on Google compared to Bing.

Google users spent around .764 seconds considering the first paid search result. Bing users spent almost double that time (1.455 sec) considering the first paid search result. Bing users spent around .7 seconds considering the first organic search result while users spent 1.059 seconds on the first organic result on Google.

What does this mean?

This could mean that people who use Bing are not as familiar with it (compared to Google users), so they need to spend a bit longer discriminating between paid and organic search results. This is supported by the fact that Google users completed tasks almost 2 seconds faster than Bing:

Also, and this is just a theory, but the gold ad icons Google uses make it really easy to breeze past and find organic results. Maybe people on Bing just don’t notice the difference between ads and organic. This is supported by the fact that Bing users spend much more time above the fold and don’t make it below the fold as often:

Conclusion

On Bing, users spend a major portion of their time considering search results (in comparison to rich text and ads off on the right side), especially the first five search results.

As a familiar and most popular search engine, Google users feel comfortable exploring the entirety of a search results page as opposed to strongly focusing in on the first elements they see. Users are comfortable viewing rich data and don’t hesitate to quickly scroll down and consider results located below the fold.

Perhaps, it is the novelty of Bing as a search engine that requires users to spend more time exploring and digesting search results.

The evolution of search engine result pages has certainly changed user behavior. The strict F pattern style we saw before is, quite frankly, no more. (At least in the contexts we researched). With the advent of rich text and ad placement, users find themselves exploring the entire results page to find what they’re looking for. As we saw through Google, many users look at rich text before even considering the actual search results.