As an optimizer, you might be thinking that user interviews fall outside your role. Or, perhaps, that they are a “nice to have” on the qualitative conversion research checklist. Worse, you might not be asking good survey questions because you’re rolling with an “I’ll just wing it” mindset.

User interviews are more complex and important than most optimizers realize.

Why Interviewing Users Isn’t What You Think It Is

User or customer interviews can help you with the design of…

- A/B tests and experiments.

- Sites and landing pages.

- Actual products.

Unfortunately, users won’t just tell you the solution, they won’t hand you the insights. Using user research to run smarter tests, design better sites and build better products is more complex than that.

In the maker / marketer bubble, things look different than they do to users. If done right, interviews will break through the bubble to help you find hidden opportunities to innovate. Or simply help you find out if you’re on the right track so far.

As Steve Portigal of Portigal Consulting explains, however, interviewing is an art that requires frequent practice…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“To learn something new requires interviewing, not just chatting. Poor interviews produce inaccurate information that can take your business in the wrong direction.

Interviewing is a skill that at times can be fundamentally different than what you do normally in conversation.

Great interviewers leverage their natural style of interacting with people but make deliberate, specific choices about what to say, when to say it, how to say it, and when to say nothing. Doing this well is hard and takes years of practice.” (via Rosenfeld)

First, you need to decide whether it makes sense for you to be conducting interviews. Many marketers believe everyone should be conducting user interviews, no matter what. Actually, you should only be conducting user interviews if…

- You don’t have the answer to an important question.

- You believe you have a solution to a problem.

So, you’re either using user interviews in a generative or evaluative manner…

- Generative: You’re interviewing people so that you can come up with new ideas.

- Evaluative: You’re interviewing people so that you can see if solutions are desirable / valuable.

Second, you need to follow a process. You need to learn and practice the art and science of user interviews. After all, anyone can invite a few users to their office for a chat, wing it and make assumptions.

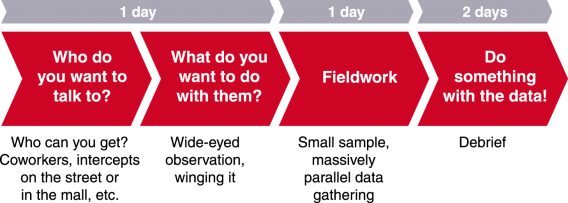

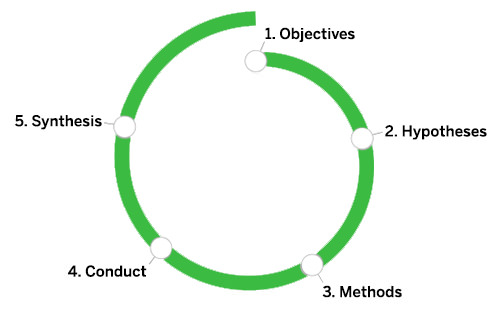

Here’s how most people see that process…

Here’s how experts like Steve see that process…

If you want to be conducting meaningful user research, you’ll need to put the extra time and effort into perfecting that more advanced process.

Creating the Research Plan & Interview Guide

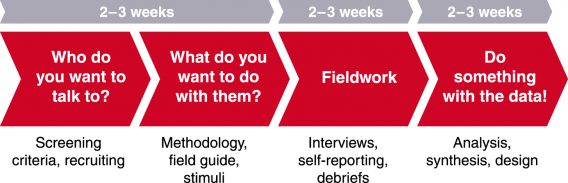

Before you go into an interview, you need to create a guide. When Steve creates an interview guide, he breaks everything down into four sections…

- Introduction: Logistics and getting to know the user’s background.

- Main Body: Your primary list of questions.

- Projection Questions: Discuss predictions for the future, ideal scenarios, etc.

- Conclusion: Wrap things up, anything you didn’t cover.

When you put it all together, you get something like this example that Steve shared in his book, Interviewing Users: How to Uncover Compelling Insights…

Before moving on, be sure to add an estimated duration for each section. You can’t anticipate all that will happen during the interview, but it’s important to be aware of what you have time for (and what you don’t). You’ll also want to give the conclusion the time it deserves. Steve explains why…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“People open up just as you’re wrapping up an interview with them. Someone compared it to what happens in psychotherapy.” (via UXmatters)

Tomer Sharon of WeWork and author of It’s Our Research also suggests creating a one-page research plan for internal stakeholders. This is particularly important if you don’t have full buy-in for this type of research and its results.

Here’s an example research plan, which clearly demonstrates the need to keep it “short and sweet”…

Tomer Sharon, WeWork:

“XYZ Phone Data-Entry Usability Test

by John Smith-Kline, Usability Researcher, [email protected]

Stakeholders: Wanda Verdi (PM), Sam Crouch (Lead Engineer)

Last updated: 13 January 2012

Background

Since January 2009, when the XYZ Phone was introduced to the world, particularly after its market release, journalists, bloggers, industry experts, other stakeholders and customers have privately and publicly expressed negative opinions about the XYZ Phone’s keyboard. These views suggest that the keyboard is hard to use and that it imposes a poor experience on customers. Some have claimed this as the main reason why the XYZ Phone will not succeed among business users. Over the years, several improvements have been made to data entry (such as using horizontal keyboards for most features), to no avail.

Goals

Identify the strengths and weaknesses of data entry on the XYZ Phone, and provide opportunities for improvement.

Research Questions

- How do people enter data on the XYZ Phone?

- What is the learning curve of new XYZ Phone users when they enter data?

- What are the most common errors users make when entering data?

Methodology

A usability study will be held in our lab with 20 participants. Each participant session will last 60 minutes and will include a short briefing, an interview, a task performance with an XYZ Phone and a debriefing. Among the tasks: enter an email subject heading, compose a long email, check news updates on CNN’s website, create a calendar event and more.

Participants

These are the primary characteristics of the study’s participants:

- Business user,

- Age 22 to 55,

- Never used an XYZ Phone,

- Expressed interest in learning more about or purchasing an XYZ Phone,

- Uses the Web at least 10 hours a week.

[Link to a draft screener]

Schedule

- Recruiting: begins on November 12

- Study day: November 22

- Results delivery: December 2

Script

TBD” (via Smashing Magazine)

The process matters. Before you head into the interview, you should have a clear idea of how it will unfold.

Of course, it likely won’t go exactly as planned and part of the process is planning for improvisation.

In fact, Slate’s Working podcast explored Stephen Colbert’s process for preparing and using questions during his interviews…

And I usually end up using 4 of the 15, and the rest of it is, what is the person just saying to me? Which makes that the most enjoyable part of the show for me. Because I started off as an improviser. I’m not a standup. I didn’t start off as a writer, I learned to write through improvisation, and so that’s the part of the show that can most surprise me. The written part of the show, I know I can get wrong. You can’t really get the interview “wrong.”

All of this talk about process makes it easy to focus more on the questions you want to ask than the answers being given. Don’t fall into that trap.

Note that this preparation process is only one small step in an even bigger process. Steve, of course, has his own, but there are many others.

For example, here’s the research learning spiral used by user researchers at frog…

Erin Muntzert, former senior design researcher at frog, invented the process…

Erin Muntzert, Google:

“The spiral is based on a process of learning and need-finding. It is built to be replicable and can fit into any part of the design process. It is used to help designers answer questions and overcome obstacles when trying to understand what direction to take when creating or moving a design forward.” (via Smashing Magazine)

Whatever your process might be, it will likely follow the prototype above. What matters is that you create and follow a systematic, repeatable process. Of course, that starts with creating a research plan for stakeholders and an interview guide for yourself and other researchers.

Recruiting Criteria

While some companies have an entire role dedicated to the user interview recruitment process, others take a more casual approach. Whether it’s grabbing strangers off the street or asking friends, it’s easier to “wing it” and hope you stumble upon something meaningful.

Steve explains why recruiting the right users is perhaps the most important part of the entire process…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“Finding people really requires a little bit of thought. You need to think about who is going to give you the best feedback: Are they current users? Are they potential users? Are they former users?

This is one of the most important parts of your project plan, actually. Finding relevant people can be a challenge.

For companies with a budget, working with a market research or recruiting firm is possible. Some companies hire staff to do full or part-time participant recruiting. For a startup, you can find users in your normal networking activities, your current business connections.” (via UX Magazine)

Be purposeful about who you recruit. Start by deciding which of the three core user groups will give you the most insight on this particular question or solution…

- Current users.

- Potential users.

- Former users.

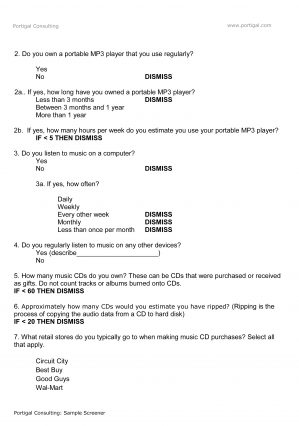

Then, use a set of screening questions to eliminate those who aren’t a good fit. Here’s an example “screener”…

Eventually, you’ll end up with a shortlist of users who are in a position to give you meaningful insights.

How to Ask Questions

When most people think “user interview”, they think “questions”. In reality, asking questions isn’t the only way to extract value. Here are just a couple examples…

- Tasks: “Draw a map of…”, “Create a new…”, “Change the style of…”

- Demonstration: “Show me how you…”

- Role-playing: “I’ll be the customer, you be the support rep…”

These types of activities are a great way to uncover opportunities you didn’t know existed. Use them to complement your questions.

When it comes to asking questions, how is just as important as what. Steve explains…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“The goal here is to make it clear to the participant (and to yourself) that they are the expert and you are the novice. This definitely pays off.

When I conduct research overseas, people tangibly extend themselves to answer my necessarily naïve questions. Although it’s most apparent in those extreme situations, it applies to all interviews.

Respect for their expertise coupled with your own humility serves as a powerful invitation to the participant.” (via Core77)

If you’re familiar with Full Catastrophe Living by Jon Kabat-Zinn, you’re familiar with the seven attitudes of mindfulness…

- Non-judging: Taking the stance of an impartial witness.

- Patience: Letting things unfold in their own time.

- Beginner’s Mind: Being receptive to new possibilities… not getting stuck in a rut of our own expertise.

- Trust: Developing a basic trust in yourself and your feelings.

- Non-Striving: Paying attention to how you are right now – however that it is. Just watch.

- Acceptance: We often waste a lot of time and energy denying what is fact.

- Letting Go: Giving up pre-existing desires and expectations.

Researchers should adopt these seven attitudes to better relate to users and encourage open dialogue. The mindset that you go into the interview with will greatly impact your results…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“One of the most significant issues is the type of questions that you ask, or how you ask those questions. I think you need to practice asking short, open-ended questions rather than long, detailed questions.

Put yourself in the mindset that you’re there to learn about that person within their framework. Don’t impose your own model on your testers, cultivate within yourself a sense of curiosity and openness and let your questioning follow that. That’s hard. It takes practice.” (via UX Magazine)

Take the time to discuss what you already know and understand about the product / site / problem and your goals. Then, David Sherwin of frog recommends framing your research using a familiar format…

David Sherwin, frog:

“These framing questions would take a ‘5 Ws and an H’ structure, similar to the questions a reporter would need to answer when writing the lede of a newspaper story:

- ‘Who?’ questions help you to determine prospective audiences for your design work, defining their demographics and psychographics and your baseline recruiting criteria.

- ‘What?’ questions clarify what people might be doing, as well as what they’re using in your website, application or product.

- ‘When?’ questions help you to determine the points in time when people might use particular products or technologies, as well as daily routines and rhythms of behavior that might need to be explored.

- ‘Where?’ questions help you to determine contexts of use — physical locations where people perform certain tasks or use key technologies — as well as potential destinations on the Internet or devices that a user might want to access.

- ‘Why?’ questions help you to explain the underlying emotional and rational drivers of what a person is doing, and the root reasons for that behavior.

- ‘How?’ questions help you go into detail on what explicit actions or steps people take in order to perform tasks or reach their goals.” (via Smashing Magazine)

Just as you would with a number of A/B test hypotheses, you’ll need to sort and prioritize your questions. If you do this successfully, as David explains, you’ll end up with a handful of research objectives…

David Sherwin, frog:

“When you have a good set of framing questions, you can prioritize and cluster the most important questions, translating them into research objectives.

Note that research objectives are not questions. Rather, they are simple statements, such as: ‘Understand how people in Western Europe who watch at least 20 hours of TV a week choose to share their favorite TV moments.’

These research objectives will put up guardrails around your research.” (via Smashing Magazine)

With your research objectives in place, you can begin to create hypotheses.

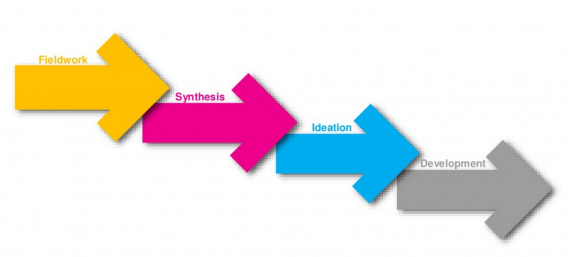

A word of caution, however. User interviews can be helpful for getting product feedback, site design feedback, new feature or test ideas, etc. But you’ll also want to use user interviews to inform the problem, not just the solution. Often, ideation comes after the fieldwork, not before.

A common mistake, according to Steve, is rushing to conduct user interviews to solve the wrong problem, to answer the wrong question.

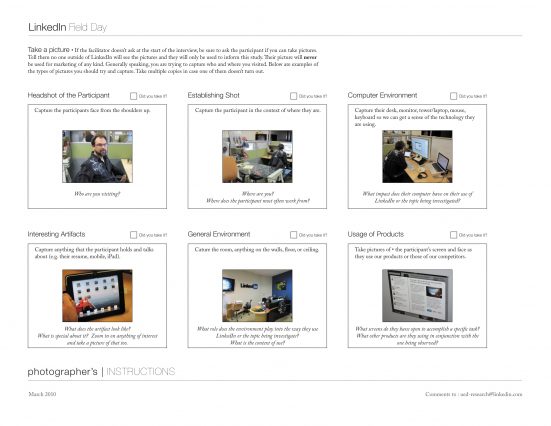

How to Document the Interview

During the interview, there should be at least two researchers present for accurate documentation. It’s important for the lead researcher to connect with the user, focus on the details, maintain eye contact and remain in the moment. Thus, the second researcher is needed for proper documentation.

Here are some general tips for documentation…

- You need to capture exactly what was said. Summaries and estimations are not enough.

- Notes are not enough. They are good for processing and making note of necessary followup questions, but they aren’t detailed enough to serve as the official record of the interview.

- Take lots of pictures. There will be things you don’t remember noticing or didn’t notice at all. Pictures can help bridge the gap.

- For the best results, use a combination of audio, video and written notes.

Here’s a storyboard style example from Steve’s book…

Notice that each stage of the interview is captured. The shots are purposeful, intentional and will support analysis later on. You can also have users take pictures as well, both during the interview and before at home.

How to Optimize the Interview

There are a few things that could go wrong during the interview, some more common than others. If you want to become a better interviewer, you’ll need to be prepared to handle these roadblocks.

1. You aren’t interviewing in person.

This is a common problem for online companies, especially. A phone interview isn’t the end of the world, but it eliminates a lot of context. So, ask the user to take pictures of their environment and describe it in detail.

The lack of body language also hinders conversation, so allow for extra silence to ensure the user has said everything she was intending to.

A Google Hangout or Skype call is a step in the right direction, but can be a disaster if Internet connections are slow or the user is not familiar with the technology. Clarify experience level and connection power before agreeing to this style of interview.

2. The user is holding back.

Be aware of the user and his style of communication. Is he really holding back or is he just slow to open up and quiet?

If he is connecting better with the second researcher, it’s a sign that your communication styles might not align. Have the second researcher lead the rest of the interview.

Often, however, it’s a matter of building a rapport and waiting for comfort to come over time. Some users need direct questions, some need back and forth chatting, some need positive reinforcement and compliments, some need you to open up about something, etc. Be willing to explore what might be making him uncomfortable, adjusting your style and questions to accommodate.

As Jenny Peggar of Gaze Ethnographic Consulting says…

Julie Peggar, Gaze Ethnographic Consulting:

“A successful field visit is one in which, at the end, the participant feels like they’ve made a new friend rather than like they’ve just been interviewed.” (via UXmatters)

(Note: While building a rapport is important, be aware that you’re conducting an interview, not having a conversation. This is hard to balance and takes a good deal of practice to perfect.)

If all else fails, you can directly ask what is making the user uncomfortable, explaining how important the interview and his comfortable level are to you.

3. The user isn’t holding back at all.

Some people really like to talk and you’ll end up with the opposite problem.

You might feel their stories are taking over the interview and pushing the conversation off-topic. Consider whether this is truly the case as it’s easy to get overly frustrated when you no longer feel in control of the interview.

Instead of interrupting, let the user finish their story or tangent and then ask a question that redirects them back to your original question. As long as you’re getting what you need from the participant, it’s better to wait it out than to interrupt the flow of the conversation.

Remember that practice makes perfect. The first time you conduct an interview, you might be half way through before you realize you’ve chosen the wrong user to engage.

Practice makes perfect. The first time, you might find yourself 10 minutes into an interview with the wrong kind of user. (That’s ok, adjust your expectations and then optimize your screener after the interview. Don’t waste the opportunity to potentially learn something unexpected.)

How to Analyze and Draw Insights

After the interviews have been conducted, the real work begins. It’s time to consider what you’ve learned, what new questions have popped up and how you can apply your data.

As David explains, this is not a quick process…

David Sherwin, frog:

“The more time you have for synthesis, the more meaning you can extract from the research data. In the synthesis stage, regularly ask yourself and your team the following questions:

- ‘What am I learning?’

- ‘Does what I’ve learned change how we should frame the original research objective?’

- ‘Did we prove or disprove our hypotheses?’

- ‘Is there a pattern in the data that suggests new design considerations?’

- ‘What are the implications of what I’m designing?’

- ‘What outputs are most important for communicating what we’ve discovered?’

- ‘Do I need to change what design activities I plan to do next?’

- ‘What gaps in knowledge have I uncovered and might need to research at a later date?’” (via Smashing Magazine)

Remember, while most people talk about user interviews for the sake of product design, this data can be used to inform A/B tests, site design, landing page design, etc. You have to look at your data through a lot of different lenses when you’re an optimizer.

That’s why it’s so unusual to conduct a series of user interviews and learn nothing new. In fact, if you feel that’s happened to you (and you were not deliberately trying to confirm / prove previous research), Steve has some advice…

Steve Portigal, Portigal Consulting:

“Not hearing anything new may be a result of not digging into the research data enough to pull out more nuanced insights. Finally, if customers are still expressing the same needs they’ve expressed before, it begs the question, ‘Why haven’t you done something about that?’” (via Rosenfeld)

Before you start digging into the research data to find insights, there are two things to remember…

- Drop your own worldview. You’re not trying to verify your assumptions, let go of your own assumptions and biases.

- Embrace other opinions. Users will see, do and describe things differently than you do. That’s ok.

You’re not digging into this data looking to confirm what you already believe, to confirm your ideal. Mindset is important.

The Analysis Process

According to Steve, there are five steps in the analysis process…

- Topline report.

- Individual analysis.

- Collaborative analysis.

- Individual analysis.

- Opportunities.

In a topline report, you identify initial areas of interest and questions you still have. Share this with stakeholders before the analysis begins, but make it clear that this will merely inform your digging.

Start by individually breaking large pieces of data into smaller pieces of data. Then, combine the smaller pieces of data into something new to develop various themes, implications and opportunities. Repeat this step multiple times.

You’ll start to notice interesting patterns, groupings, clusters, etc. Make reactive notes on those findings. Anything that seems interesting or intriguing should be noted. Think of this as a form of segmentation. You have a lot of data and you’re slicing and dicing it to find interesting insights.

Remember, a user won’t just hand you an interesting insight. You need to dig for and extract it.

After this individual analysis, come together as a group. Treat each interview as a case study. Pick out the highlights and document them on stickies. (For best results, code the stickies with the source.) Now, look for patterns. What seems to fit together? This could be what people think, do, feel, etc.

Now, regroup the highlights at a higher level. What does all of this mean? This could be what people want, need, fear, etc. Name these final high level groups as they’re your themes and each sticky in each group is supporting evidence.

User research models and frameworks can go a long way in helping with this analysis, but that would be an entirely new article.

After the group work, it might make sense to break out as individuals once more. By inputting all of the sticky comments into a spreadsheet, you can slice and dice even more.

What’s important now is to remember that opportunities aren’t a list of solutions. According to Steve, they’re…

- Change you can imagine based on what you observed.

- About people.

- In the context of, but reframing business questions.

- Generative, inviting many solutions.

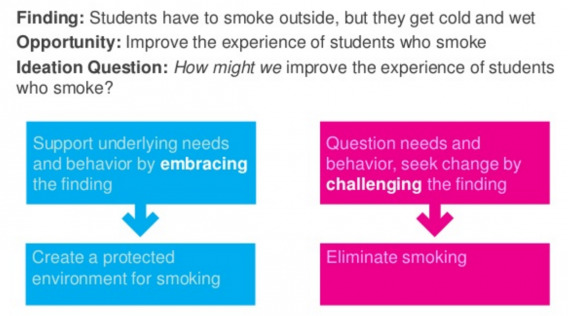

So, to make opportunities actionable, add “how might we” and brainstorm with the group. Be sure to consider all of the options. What areas of the business can be changed? What are your options for solving the issue?

Then, simply prioritize based on anticipated impact.

In the end, you will be left with…

- New questions to research.

- A long list of opportunities, whether that’s product ideas, design ideas or A/B test ideas.

Conclusion

User interviews are complex, but when they’re done well, they can lead to some of the smartest product, web design and A/B test hypotheses. Don’t leave “user interviews” sitting at the bottom of your qualitative research checklist.

Here’s how to give user interviews the attention they deserve…

- Create a research plan for stakeholders and an interview guide for yourself and other researchers.

- Focus on developing a systematic, repeatable process.

- Create a screener to ensure you’re recruiting the right type of user.

- User interviews can either inform the problem or the solution. Generate a list of questions to help you.

- Have at least two researchers present to ensure the interview is well documented (audio, video, notes).

- Prepare for interviews that can’t be face-to-face, the user holding back and the user being too chatty. This takes practice.

- Develop a topline report for stakeholders and then segment your data to draw out the opportunities, which can be prioritized and turned into optimization hypotheses.

I just discovered the jobs-to-be-done method yesterday. I think that framework does a better job at uncovering sub-rationality in purchasing decisions. That is, system 1 or subconscious reasoning. It relies more on associations, emotional context, and the functional, emotional, or social pay-off storyline.

https://jtbd.info/uncovering-the-jobs-that-customers-hire-products-and-services-to-do-834269006f50#.mwdwpiazu

Thanks for sharing this, Peter. Excited to check it out.